“Scheherazade”

Czech National Ballet

National Theatre

Prague, Czech Republic

June 21, 2025 (matinee)

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2025 by Ilona Landgraf

To be upfront, Mauro Bigonzetti’s new Scheherazade for the Czech National Ballet is no asset to its repertory. Its choreography is meager and the plot thin; the characters lack depth, and the digital set design is unconvincing.

To be upfront, Mauro Bigonzetti’s new Scheherazade for the Czech National Ballet is no asset to its repertory. Its choreography is meager and the plot thin; the characters lack depth, and the digital set design is unconvincing.

Bigonzetti takes up the narrative thread where Fokine’s 1910 Scheherazade for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes ends. Zobeida, the favorite but unfaithful wife of Shahryar, the king of Persia, had died. Enraged about womanhood in general, Shahryar took revenge by killing every woman he slept with the morning after their first night together. Scheherazade, the clever daughter of his vizier, put a stop to the slaughter. The tales she narrated to the king each night (collected in the Middle Eastern folk tale, One Thousand and One Nights) softened him.

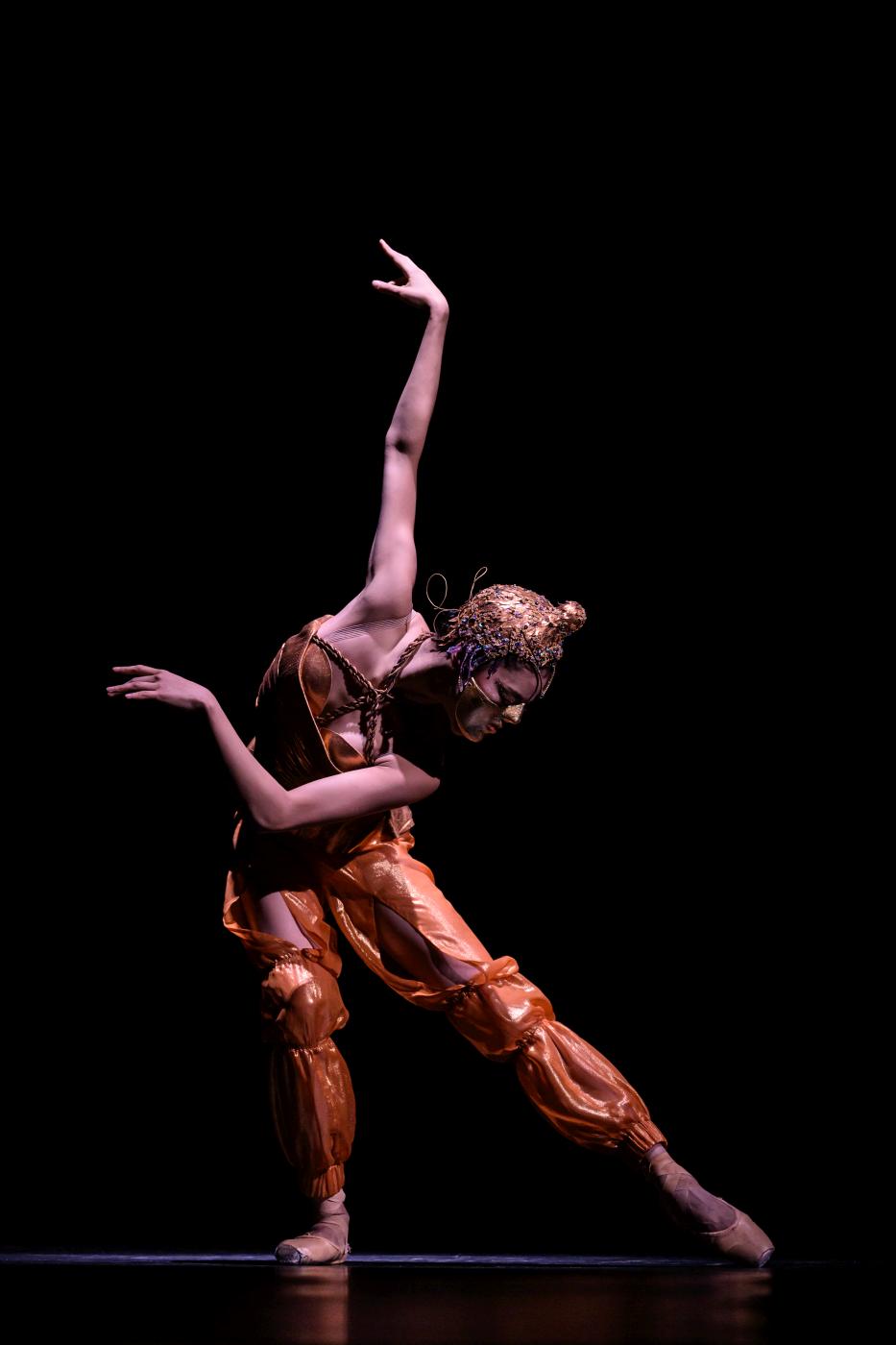

Bigonzetti portrayed the women in line for Shahryar, among them Scheherazade (Nana Nakagawa), who was ready to sacrifice herself.

Ambiguous movements made it difficult to discern their natures. Elegant and spiky sequences seemed to alternate randomly, flexed feet spoiled the lines, and hips gyrated but weren’t enticing. Little of these modern Orientals radiated beauty. Panels of rippling silky fabric (hanging from above like curtains and, later, symbolizing a connective bond between the women) and shawls that fluttered through the air in a ribbon-like dance distracted the eye from the limited choreography.

Ambiguous movements made it difficult to discern their natures. Elegant and spiky sequences seemed to alternate randomly, flexed feet spoiled the lines, and hips gyrated but weren’t enticing. Little of these modern Orientals radiated beauty. Panels of rippling silky fabric (hanging from above like curtains and, later, symbolizing a connective bond between the women) and shawls that fluttered through the air in a ribbon-like dance distracted the eye from the limited choreography.

Video projections by OOOPSudio transported the audience into Shahryar’s (Giovanni Rotolo’s) palace, through whose hall snappy court society darted, either hopping on both feet or turning pirouettes.

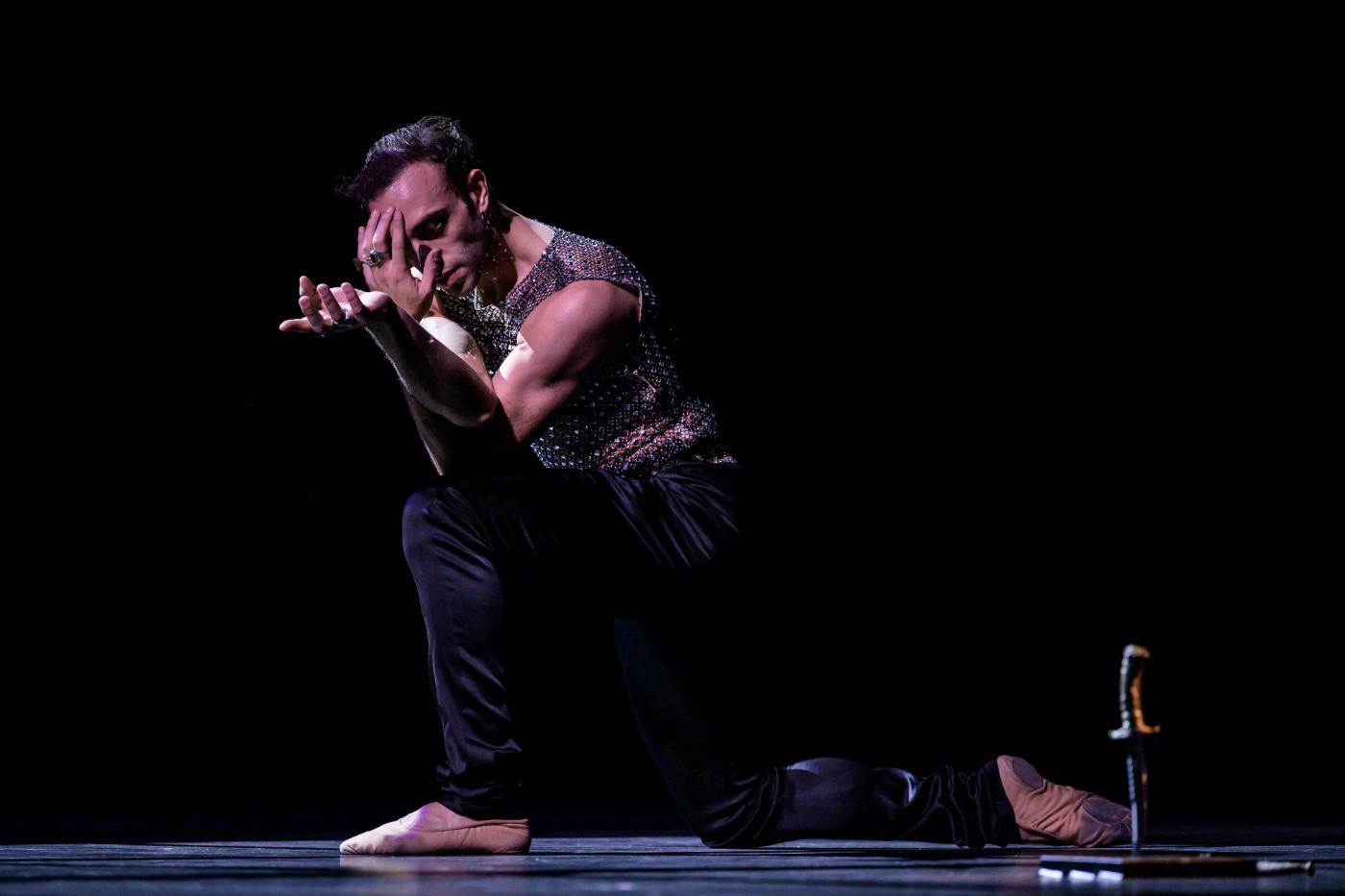

Shahryar’s characterization was blunt. A silent darkness represented his mental state; a stiff, pompous cloak closed with a grid collar (costumes by Anna Biagiotti) either imprisoned or protected him. Even after slipping out of it, he remained static and brooding. The knife in his overly beringed hand was connected to the huge splashes of blood on the backdrop. Suddenly, the seductive violin melody of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade composition began to sing. It sounded out of place, like a far cry from cultured times. The violin accompanied the king as he entered a glass dome reminiscent of a space travel command center. He threw himself to the floor, ready to beat himself, but instead his movements alternated between sharp jerks and freezing.

Shahryar’s characterization was blunt. A silent darkness represented his mental state; a stiff, pompous cloak closed with a grid collar (costumes by Anna Biagiotti) either imprisoned or protected him. Even after slipping out of it, he remained static and brooding. The knife in his overly beringed hand was connected to the huge splashes of blood on the backdrop. Suddenly, the seductive violin melody of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade composition began to sing. It sounded out of place, like a far cry from cultured times. The violin accompanied the king as he entered a glass dome reminiscent of a space travel command center. He threw himself to the floor, ready to beat himself, but instead his movements alternated between sharp jerks and freezing.

Heavy yellow smoke billowed in a video as the scene changed to a vaulted oriental hall, photos of which lined the backdrop. In each photo, the hall glowed as if burning hot. From there, two men dragged Scheherazade to the king. Although she was resolved to become his next lover, she fought her captors and flailed her legs while being carried past a blood-smeared wall. Her fate seemed to be part of the assembly line of women that Shahryar’s men delivered to him. Each woman was thrown, thrashing, into Shahryar’s arms, whose brief yank broke their necks. Shahryar dragged one woman across the floor like slain game and overstretched her leg as if to tear it out before strangling her. He then flung his coat off and screamed, which brought Rimsky-Korsakov’s music to a sudden halt.

Heavy yellow smoke billowed in a video as the scene changed to a vaulted oriental hall, photos of which lined the backdrop. In each photo, the hall glowed as if burning hot. From there, two men dragged Scheherazade to the king. Although she was resolved to become his next lover, she fought her captors and flailed her legs while being carried past a blood-smeared wall. Her fate seemed to be part of the assembly line of women that Shahryar’s men delivered to him. Each woman was thrown, thrashing, into Shahryar’s arms, whose brief yank broke their necks. Shahryar dragged one woman across the floor like slain game and overstretched her leg as if to tear it out before strangling her. He then flung his coat off and screamed, which brought Rimsky-Korsakov’s music to a sudden halt.

Scheherazade walked for a long time between the corpses, which, after some time, came to life. To prepare herself for her encounter with Shahryar, she gave her headdress and jewelry to other women and, for some reason, pulled red ribbon from her mouth. After cutting a lock of her hair, she thrust Shahryar’s knife into the floor. The firestorm raging behind her indicated that the story was close to its climax. Although nothing in Scheherazade’s appearance indicated any special power, Shahryar backed off the moment she approached him. She immediately dominated him and stood on his chest, pushed him around, and flew into his arms like a redeeming dove. Chastening him was easier than previously thought. The violin played at a high pitch as Shahryar knelt on the floor, his bare chest bent back toward the audience, and his gaze lost.

Scheherazade walked for a long time between the corpses, which, after some time, came to life. To prepare herself for her encounter with Shahryar, she gave her headdress and jewelry to other women and, for some reason, pulled red ribbon from her mouth. After cutting a lock of her hair, she thrust Shahryar’s knife into the floor. The firestorm raging behind her indicated that the story was close to its climax. Although nothing in Scheherazade’s appearance indicated any special power, Shahryar backed off the moment she approached him. She immediately dominated him and stood on his chest, pushed him around, and flew into his arms like a redeeming dove. Chastening him was easier than previously thought. The violin played at a high pitch as Shahryar knelt on the floor, his bare chest bent back toward the audience, and his gaze lost.

Václav Zahradník and the orchestra of the National Theatre did their accompaniment for Rimsky-Korsakov’s iridescent Scheherazade score (to which Bigonzetti added Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sinfonietta on Russian Themes). Yet its allure suffered from the gloom onstage.

| Links: | Website of the Czech National Theatre | |

| “Scheherazade” – The Making Of | ||

| “Scheherazade” – Trailer | ||

| Photos: | 1. | Nana Nakagawa (Scheherazade), “Scheherazade” by Mauro Bigonzetti, Czech National Ballet 2025 |

| 2. | Giovanni Rotolo (Shahryar), “Scheherazade” by Mauro Bigonzetti, Czech National Ballet 2025 |

|

| 3. | Nana Nakagawa (Scheherazade), “Scheherazade” by Mauro Bigonzetti, Czech National Ballet 2025 | |

| 4. | Giovanni Rotolo (Shahryar), “Scheherazade” by Mauro Bigonzetti, Czech National Ballet 2025 |

|

| 5. | Giovanni Rotolo (Shahryar) and ensemble, “Scheherazade” by Mauro Bigonzetti, Czech National Ballet 2025 | |

| 6. | Nana Nakagawa (Scheherazade), “Scheherazade” by Mauro Bigonzetti, Czech National Ballet 2025 | |

| 7. | Nana Nakagawa (Scheherazade) and ensemble, “Scheherazade” by Mauro Bigonzetti, Czech National Ballet 2025 | |

| 8. | Nana Nakagawa (Scheherazade) and ensemble, “Scheherazade” by Mauro Bigonzetti, Czech National Ballet 2025 | |

| 9. | Nana Nakagawa (Scheherazade) and Giovanni Rotolo (Shahryar), “Scheherazade” by Mauro Bigonzetti, Czech National Ballet 2025 | |

| 10. | Nana Nakagawa (Scheherazade) and Giovanni Rotolo (Shahryar), “Scheherazade” by Mauro Bigonzetti, Czech National Ballet 2025 | |

| all photos © Serghei Gherciu | ||

| Editing: | Kayla Kauffman |