“La Fille du Pharaon”

Bolshoi Ballet

Bolshoi Theatre

Moscow, Russia

February 16, 2024

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2024 by Ilona Landgraf

The Bolshoi Ballet’s La Fille du Pharaon is about an Egyptian pipe dream—and it felt like a dream indeed. I was already impressed in 2019 when I watched it for the first time. Five years later, the cultural landscape has changed so much that its magnificence seems surreal. It highlights the extent to which the paths of Western and Russian cultures have diverged. While European culture finds itself on shaky grounds, the Bolshoi stands firm as a rock. The critics who argue that Pierre Lacotte’s recreation of Marius Petipa’s La Fille du Pharaon (1862) is like unearthing a dusty ballet mummy are wrong. True, the piece’s libretto (which is based on Theophile Gautier’s 1857 Le Roman de la Momie and was edited by Lacotte) is flimsy. Hearty drags on an opium pipe transport a traveling Englishman and his servant to the pyramids during the reign of a mighty pharaoh. This pharaoh has a daughter who instantly falls in love with the Englishman. After some adventurous trouble (including the dispatch of a lion, a last-minute escape, a nearly murderous assault, a suicide attempt, and the hero’s near execution), the lovers are happily united. But – alas! Upon awakening, it turns out that it had all been nothing but a dream. It’s a well-trod and thoroughly implausible plot. But who cares given the superabundance of (French style)

The Bolshoi Ballet’s La Fille du Pharaon is about an Egyptian pipe dream—and it felt like a dream indeed. I was already impressed in 2019 when I watched it for the first time. Five years later, the cultural landscape has changed so much that its magnificence seems surreal. It highlights the extent to which the paths of Western and Russian cultures have diverged. While European culture finds itself on shaky grounds, the Bolshoi stands firm as a rock. The critics who argue that Pierre Lacotte’s recreation of Marius Petipa’s La Fille du Pharaon (1862) is like unearthing a dusty ballet mummy are wrong. True, the piece’s libretto (which is based on Theophile Gautier’s 1857 Le Roman de la Momie and was edited by Lacotte) is flimsy. Hearty drags on an opium pipe transport a traveling Englishman and his servant to the pyramids during the reign of a mighty pharaoh. This pharaoh has a daughter who instantly falls in love with the Englishman. After some adventurous trouble (including the dispatch of a lion, a last-minute escape, a nearly murderous assault, a suicide attempt, and the hero’s near execution), the lovers are happily united. But – alas! Upon awakening, it turns out that it had all been nothing but a dream. It’s a well-trod and thoroughly implausible plot. But who cares given the superabundance of (French style)  dance that Lacotte incorporated? It was dancing of a complexity that only the Bolshoi can deliver. That’s why he recreated this ballet in 2000 just for them. It deepens the company’s roots in the legacy; it has the vibes of the Imperial Russian Ballet and the glorious ballerinas who excelled in the leading role, Kschessinska and Pavlova among them. Lacotte’s recreation of the splendid set design (a lush oasis, a gargantuan Egyptian palace hall, a fisherman’s hut, the realm of Neptune at the bottom of the Nile, and the courtyard of the palace) and the no less magnificent costumes recall the 19th century’s fascination for the ancient Orient’s exoticism.

dance that Lacotte incorporated? It was dancing of a complexity that only the Bolshoi can deliver. That’s why he recreated this ballet in 2000 just for them. It deepens the company’s roots in the legacy; it has the vibes of the Imperial Russian Ballet and the glorious ballerinas who excelled in the leading role, Kschessinska and Pavlova among them. Lacotte’s recreation of the splendid set design (a lush oasis, a gargantuan Egyptian palace hall, a fisherman’s hut, the realm of Neptune at the bottom of the Nile, and the courtyard of the palace) and the no less magnificent costumes recall the 19th century’s fascination for the ancient Orient’s exoticism.

The evening’s cast was stellar. As the pharaoh’s daughter, Aspicia, Elizaveta Kokoreva sailed effortlessly through a seemingly never-ending array of pas de deux, turning each one into a marvel. After having watched her on stage several times, I started to believe that she was sent from heaven. However, I didn’t know the other leading dancer, Dmitry Smilevsky. He played the Englishman, Lord Wilson, who turns into the Egyptian Taor in his dream. Similar to Kokoreva, Smilevsky graduated from the Moscow State Academy of Choreography in 2019 and joined the Bolshoi in the same year.

There, he soared through the ranks like a rocket. Last year, the company’s artistic director, Makhar Vaziev, doubled down, promoting Smilevsky to first soloist and – soon after – to principal. That suggests that Smilevsky is brilliant—and that’s exactly how his Taor was. I didn’t spot the slightest flaw. He is a freshly promoted young dancer who already delivers top-notch quality. Where might that lead?

There, he soared through the ranks like a rocket. Last year, the company’s artistic director, Makhar Vaziev, doubled down, promoting Smilevsky to first soloist and – soon after – to principal. That suggests that Smilevsky is brilliant—and that’s exactly how his Taor was. I didn’t spot the slightest flaw. He is a freshly promoted young dancer who already delivers top-notch quality. Where might that lead?

Unlike Petipa, Lacotte gave almost all supporting characters a chance to dance. Georgy Gusev turned some merry rounds as Lord Wilson’s, and respectively Taor’s, servant, Passiphonte. As Ramze, Aspicia’s Nubian slave, Maria Mishina chaperoned her mistress and also a group of children. Her complicity helped the lovers to elope. Another slave (Anton Savichev) played a rather inglorious role in the escape and came to an ill end.

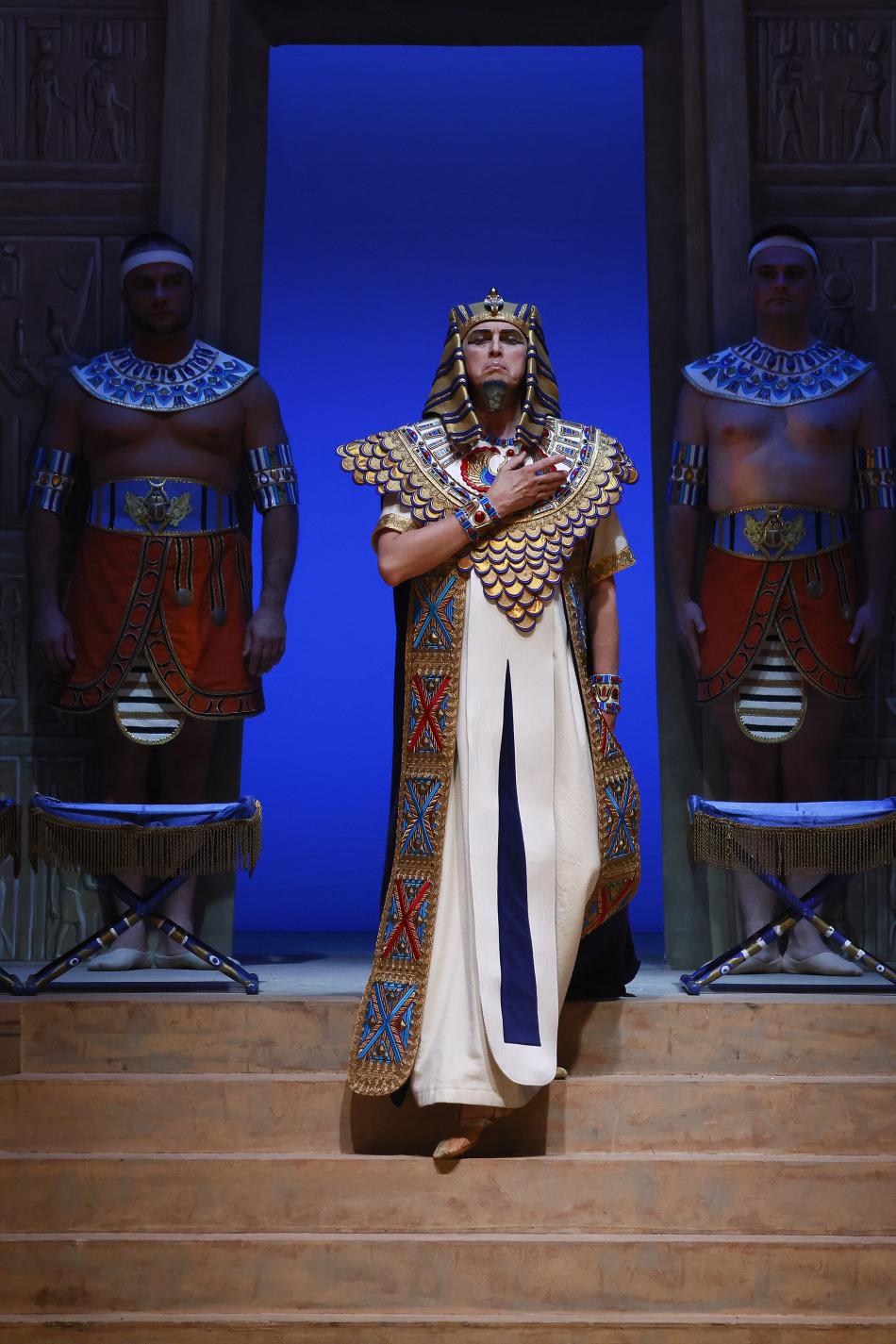

Olga Marchenkova and Egor Gerashchenko portrayed the hospitable fishermen who welcome the refugees. Unfortunately, their hut turned out to not be the safest place to hide. The King of Nubia (Yuri Ostrovsky), struck to the core by Aspicia’s refusal to marry him, found her there with his dagger ready in hand. His treachery later cost him the friendship of the pharaoh (Alexey  Loparevich). Aspicia saved herself with a plucky jump into the Nile, at the bottom of which she was greeted by the River God (Nikita Kapustin) and his court, including representatives of other major rivers. The castanets that Kristina Petrova clattered during her solo marked her as Spain’s Guadalquivir; the pings of a triangle accompanied the solo of the river Congo (Angelina Vlashinets), while the Russian Neva (Antonina Chapkina) flew gently like a reverie. Alexey Matrakhov played the bouncy monkey who was eager for oranges. Of the other animals on stage, the white horse that pulled the pharaoh’s chariot behaved professionally, the (stuffed) lion was quickly captured, and the venomous snake was kind enough to stay in its basket.

Loparevich). Aspicia saved herself with a plucky jump into the Nile, at the bottom of which she was greeted by the River God (Nikita Kapustin) and his court, including representatives of other major rivers. The castanets that Kristina Petrova clattered during her solo marked her as Spain’s Guadalquivir; the pings of a triangle accompanied the solo of the river Congo (Angelina Vlashinets), while the Russian Neva (Antonina Chapkina) flew gently like a reverie. Alexey Matrakhov played the bouncy monkey who was eager for oranges. Of the other animals on stage, the white horse that pulled the pharaoh’s chariot behaved professionally, the (stuffed) lion was quickly captured, and the venomous snake was kind enough to stay in its basket.

Pavel Klinichev and the Bolshoi Orchestra ensured that Cesare Pugni’s score and the performance on stage merged marvelously.

| Links: | Website of the Bolshoi Theatre | |

| “La Fille du Pharaon” – Rehearsal | ||

| “La Fille du Pharaon” – Revival | ||

| Homage to Pierre Lacotte | ||

| Photos: | 1. | Maria Mishina (Ramze), Elizaveta Kokoreva (Aspicia), and ensemble; “La Fille du Pharaon” by Pierre Lacotte, Bolshoi Ballet 2024 |

| 2. | Elizaveta Kokoreva (Aspicia), Maria Mishina (Ramze), and ensemble; “La Fille du Pharaon” by Pierre Lacotte, Bolshoi Ballet 2024 |

|

| 3. | Elizaveta Kokoreva (Aspicia) and ensemble, “La Fille du Pharaon” by Pierre Lacotte, Bolshoi Ballet 2024 |

|

| 4. | Alexey Loparevich (Pharaoh), “La Fille du Pharaon” by Pierre Lacotte, Bolshoi Ballet 2024 | |

| 5. | Dmitry Smilevsky (Taor) and Elizaveta Kokoreva (Aspicia), “La Fille du Pharaon” by Pierre Lacotte, Bolshoi Ballet 2024 | |

| 6. | Dmitry Smilevsky (Taor), Elizaveta Kokoreva (Aspicia), and ensemble; “La Fille du Pharaon” by Pierre Lacotte, Bolshoi Ballet 2024 |

|

| all photos © Bolshoi Ballet / Damir Yusupov | ||

| Editing: | Kayla Kauffman |