“Shostakovich Trilogy”

Dutch National Ballet

Dutch National Opera & Ballet

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

June 17, 2017

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2017 by Ilona Landgraf

“Ted, I don’t know what you’re doing with the company,” Alexei Ratmansky said after the premiere of his “Shostakovich Trilogy” at Dutch National Ballet, “but they get better and better.” He was right to praise the dancers. Their dedication and attention to detail – and this piece is replete with details – made the evening a thorough success.

“Ted, I don’t know what you’re doing with the company,” Alexei Ratmansky said after the premiere of his “Shostakovich Trilogy” at Dutch National Ballet, “but they get better and better.” He was right to praise the dancers. Their dedication and attention to detail – and this piece is replete with details – made the evening a thorough success.

“Shostakovich Trilogy” is the sixth piece by Ratmansky to enter the company’s repertoire and, next to “Don Quichotte”, is the second full-evening one. The piece does not only challenge the dancers, but also proves a hard nut to crack for the audience as well. Repeated viewing is  recommended, as is knowledge about Shostakovich’s life and about Russian history and culture. Although the ballet’s three parts are not narratives, they tell a story. They reflect the composer’s life, his work, and the political and social climate he experienced.

recommended, as is knowledge about Shostakovich’s life and about Russian history and culture. Although the ballet’s three parts are not narratives, they tell a story. They reflect the composer’s life, his work, and the political and social climate he experienced.

Shostakovich is considered a poly-stylist. Ratmansky, too, seems to draw on unlimited choreographic resources, which he exploits without reserve. The steps, ideas, and associations that he worked with in only the first part of the triad other choreographers might have stretched to fill a whole-evening ballet. I regretted every moment that I spent taking notes, knowing that I couldn’t anticipate or predict what would happen onstage. Group formations changed constantly and, above all, rapidly but, as if drawing a wide variety of patterns without lifting pen from paper, Ratmansky maintained a connecting thread. For example, phrases from earlier segments were brought back later, serving as visual cues.

In 2014 Ratmansky played down the significance of his art form in an interview, saying “(…) ballet is just dancing. We can’t compete with literature, with philosophy.” “Shostakovich Trilogy” is one of many examples that prove him wrong. Beyond not knowing how many pages an author would need to present in words what Ratmansky expresses in dance, I think even finding the right words would be difficult.

In 2014 Ratmansky played down the significance of his art form in an interview, saying “(…) ballet is just dancing. We can’t compete with literature, with philosophy.” “Shostakovich Trilogy” is one of many examples that prove him wrong. Beyond not knowing how many pages an author would need to present in words what Ratmansky expresses in dance, I think even finding the right words would be difficult.

Ratmansky used three different compositions by Shostakovich for the trilogy. Symphony No. 9 accompanies the first part. The composition dates from 1949 and was meant to celebrate, either just initially or more fully, the Russian victory over Nazi Germany in World War II. An atmosphere of gaiety, playfulness, brilliance, and bite suffuses the music. Accordingly, the dance had an exuberant and teasing cheerfulness. One would have  almost thought that the dancers had sipped some champagne in advance, if not an oppressive element had gradually crept in. Movements, formerly light and airborne, were suddenly directed downwards, as if trying to avoid touching the upper sphere.

almost thought that the dancers had sipped some champagne in advance, if not an oppressive element had gradually crept in. Movements, formerly light and airborne, were suddenly directed downwards, as if trying to avoid touching the upper sphere.

The backdrop (credited to George Tsypin) changed, now depicting drawings of people walking – model citizens or national heroes, maybe – some of them carrying red banners. Dancers lined up in rank and file, marched ostentatiously, smiling and swaggering. Suddenly, some of the group collapsed to the ground. Their bodies broke down bit by bit, as if dying in installments before all resumed their cheerful hopping.

Keso Dekker’s costumes were black for corps dancers and brown / black or green / black for soloists. However, in terms of the choreography, the differentiation between the two groups was sometimes blurred. Of the two leading couples, Suzanna Kaic and Edo Wijnen seemed to be engaged in shenanigans, whereas Wen Ting Guan and Jozef Varga portrayed a couple (possibly Shostakovich and his first wife Nina Varzar) repeatedly stricken by apprehension. They moved with stooped posture, staying close to each other, checking their surroundings carefully. The pair was separated twice and, although not much had happened, one had the feeling that they had been put through the mill by the two men lifting and bending each of them.

Keso Dekker’s costumes were black for corps dancers and brown / black or green / black for soloists. However, in terms of the choreography, the differentiation between the two groups was sometimes blurred. Of the two leading couples, Suzanna Kaic and Edo Wijnen seemed to be engaged in shenanigans, whereas Wen Ting Guan and Jozef Varga portrayed a couple (possibly Shostakovich and his first wife Nina Varzar) repeatedly stricken by apprehension. They moved with stooped posture, staying close to each other, checking their surroundings carefully. The pair was separated twice and, although not much had happened, one had the feeling that they had been put through the mill by the two men lifting and bending each of them.

At one point, Varga joined the back ranks of the marching group, but peeled off soon after. Standing alone on stage, he was eyeballed by four men, who had crept in softly. Upon Varga’s brisk gesture, a winds solo began, which totally distracted the men. For now, it seemed he had his peace. The mob was silenced by a new composition.

At one point, Varga joined the back ranks of the marching group, but peeled off soon after. Standing alone on stage, he was eyeballed by four men, who had crept in softly. Upon Varga’s brisk gesture, a winds solo began, which totally distracted the men. For now, it seemed he had his peace. The mob was silenced by a new composition.

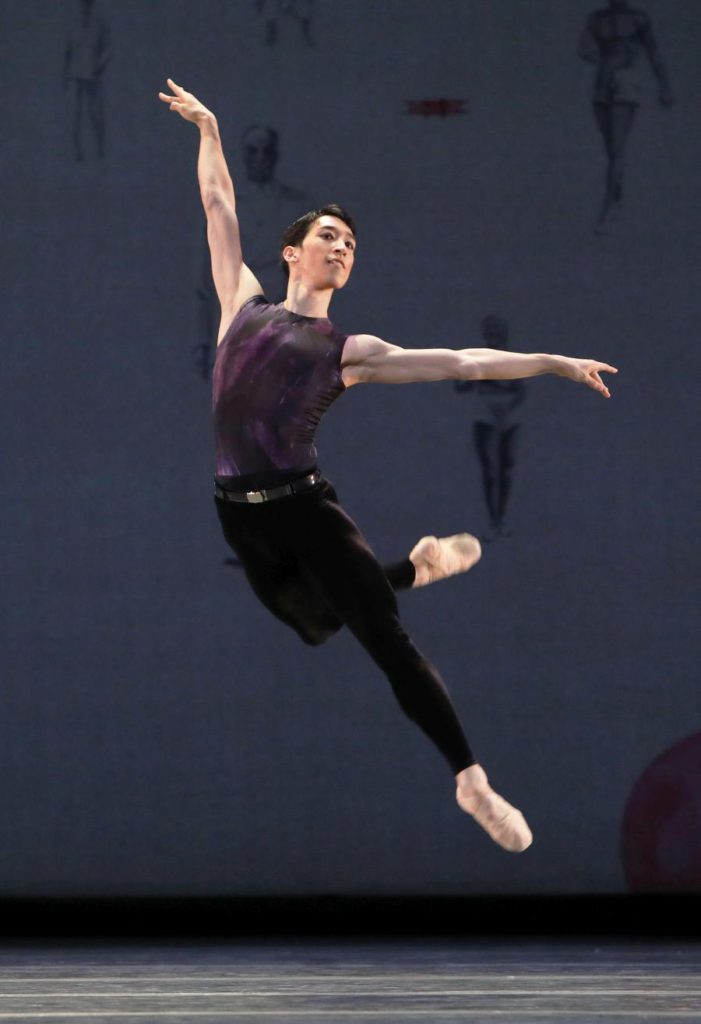

According to one dancer, Sho Yamada’s role was that of the angel. Indeed, Yamada was exposed. He appeared to be upbeat, hardly ever joining the group, but instead seemed to be their whisperer or a hybrid of tummler and manipulator. His turns, fired off towards the end of the piece, made the semicircle of dancers that surrounded him run like a machine set in motion.

The String Quartet No. 8, chosen for the trilogy’s second part, was Shostakovich’s musical response to a period of personal crisis in 1960. For one thing, he couldn’t avoid joining the Communist Party that time; for another, his health began to deteriorate. The Quartet had biographical intent – and so too did the choreography, which was full of biographical references.

The String Quartet No. 8, chosen for the trilogy’s second part, was Shostakovich’s musical response to a period of personal crisis in 1960. For one thing, he couldn’t avoid joining the Communist Party that time; for another, his health began to deteriorate. The Quartet had biographical intent – and so too did the choreography, which was full of biographical references.

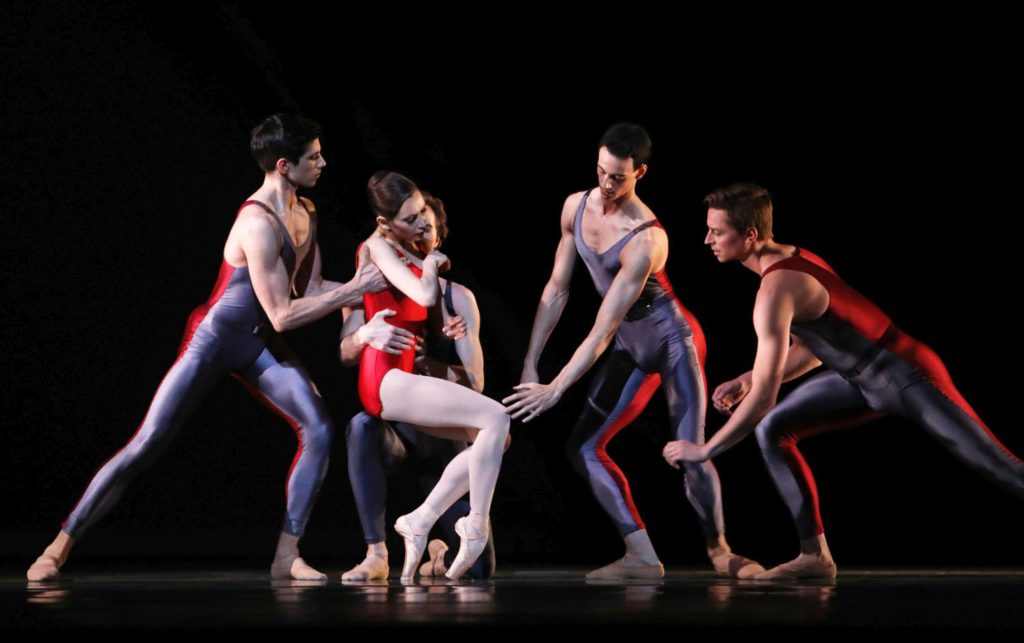

Daniel Camargo, wearing a black suit without a shirt, portrayed the desperate, drained composer. Did Naira Agvanean, Sasha Mukhamedov and Emanouela Merdjanova depict Shostakovich’s three spouses? Or did only one dance the role of his wife, while the other two depicted his pupils, Galina Ustvolskaya and Elmira Nazirova, with whom Shostakovich had close relationships? We don’t know.

What became clear, though, was that neither relationship was easy. The women seemed to flee his arms – and yet Shostakovich also abandoned one, at least for a time. Was this an allusion to his divorce from Nina Varzar, which was followed by a re-marriage? One woman returned after playing coy several times; Shostakovich kissed her, yet the way she hung over him while being lifted didn’t look as though their love was flying high. Also, during their subsequent pas de deux, neither related to each other, instead performing almost unrelated solos next to each other.

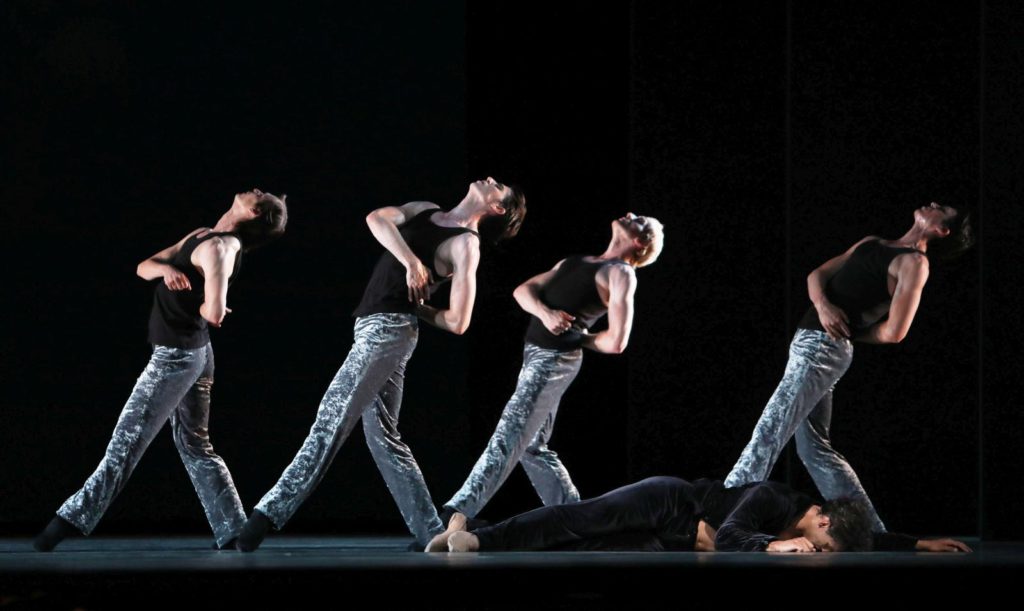

A second attempt to pursue a romance with one woman (Agvanean) ended with her collapsing to the floor. A line of three men in silver pants (the regime?) crossed Shostakovich’s path, reminding him and us that he was perpetually on the radar of the authorities. The following love affair seemed happy, even though other dancers sneered mockingly at the couple, but the woman (Mukhamedov) soon died. She, or presumably her spirit, was later carried back on stage by the same men. Both lovers yearningly stretched out their arms, but they couldn’t reach each other. The last women to return was Merdjanova. Happiness briefly flickered, but suddenly Merdjanova disappeared.

A second attempt to pursue a romance with one woman (Agvanean) ended with her collapsing to the floor. A line of three men in silver pants (the regime?) crossed Shostakovich’s path, reminding him and us that he was perpetually on the radar of the authorities. The following love affair seemed happy, even though other dancers sneered mockingly at the couple, but the woman (Mukhamedov) soon died. She, or presumably her spirit, was later carried back on stage by the same men. Both lovers yearningly stretched out their arms, but they couldn’t reach each other. The last women to return was Merdjanova. Happiness briefly flickered, but suddenly Merdjanova disappeared.

Shostakovich never lost hope that he might find love. If his affection was answered, his mood brightened, but this single ray of light couldn’t compensate for the blows of fate. Every romance brought his smile back, but it became more fragile, worn-down by painful experience.

Shostakovich never lost hope that he might find love. If his affection was answered, his mood brightened, but this single ray of light couldn’t compensate for the blows of fate. Every romance brought his smile back, but it became more fragile, worn-down by painful experience.

Camargo poignantly conveyed Shostakovich’s gradually rigidifying depression. The grief he poured on stage was hard to digest. At the end, left alone by the women, he arranged the other dancers into a beautiful tableaux (a new composition?), then turned his back to them and walked towards the backside of the stage. He was a wreck, no longer interested in his work.

Camargo poignantly conveyed Shostakovich’s gradually rigidifying depression. The grief he poured on stage was hard to digest. At the end, left alone by the women, he arranged the other dancers into a beautiful tableaux (a new composition?), then turned his back to them and walked towards the backside of the stage. He was a wreck, no longer interested in his work.

The backdrop showed cubistic portraits of men with clear-cut features, occasionally covered by black face masks. Maybe those were the faces Shostakovich needed to hide behind?

The second part, at the heart of the trilogy, conveyed a deep sadness that retrospectively marred the lightness of the first. These insights into Shostakovich’s private life also changed our perspective on the third part. It was set to the Piano Concerto No. 1, a composition from 1933 involving a solo trumpet. Many other musical works are quoted by or parodied in the concerto. The trumpet frequently interjects sarcastically to the witty, humorous piano passages.

The second part, at the heart of the trilogy, conveyed a deep sadness that retrospectively marred the lightness of the first. These insights into Shostakovich’s private life also changed our perspective on the third part. It was set to the Piano Concerto No. 1, a composition from 1933 involving a solo trumpet. Many other musical works are quoted by or parodied in the concerto. The trumpet frequently interjects sarcastically to the witty, humorous piano passages.

The concerto came to life three years before Shostakovich fell from official favor in 1936, the same time the Great Terror began. Ratmansky preempted the double-game that Shostakovich was forced to play from then on. His choreography is as

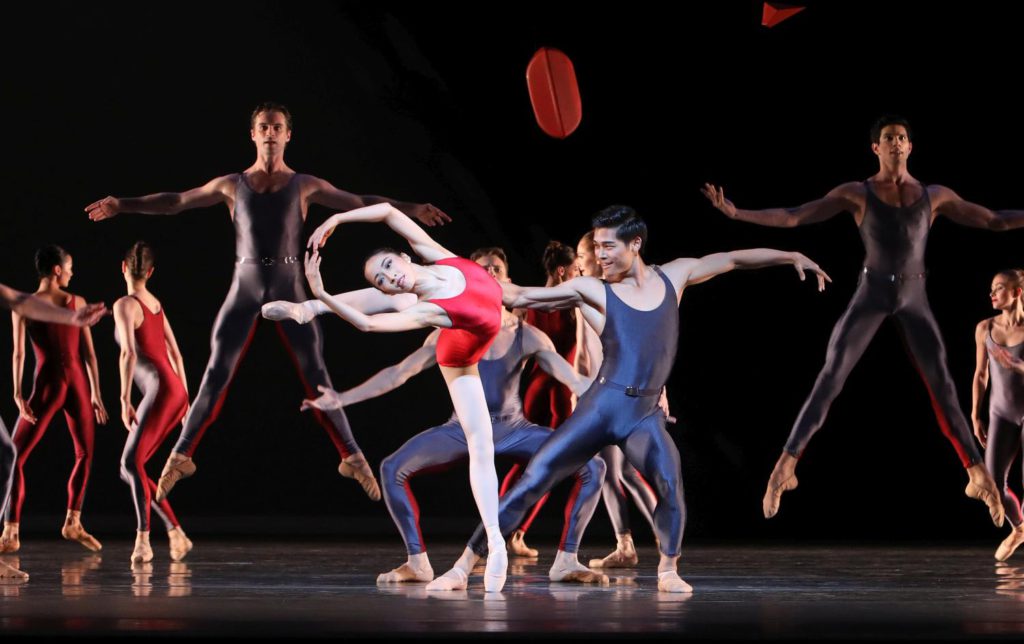

Janus-faced as the costumes (shiny full-body leotards for group dancers; gray on the front side, red on the backside). At times the dance had an air of triumph, as if being performed for propaganda purposes. The playfulness in the first part had been genuine, but now the dance looked well-calculated, like a machine with perfectly interlocking parts. But the fake was so skillfully done, that one was easily carried away and merely enjoyed the firework of quick changes happening onstage. Jumps and turns ended in poses, like

Janus-faced as the costumes (shiny full-body leotards for group dancers; gray on the front side, red on the backside). At times the dance had an air of triumph, as if being performed for propaganda purposes. The playfulness in the first part had been genuine, but now the dance looked well-calculated, like a machine with perfectly interlocking parts. But the fake was so skillfully done, that one was easily carried away and merely enjoyed the firework of quick changes happening onstage. Jumps and turns ended in poses, like  notes highlighted with an exclamation point, that were accurately aligned with the tones of the trumpet or used as a means to chase another dancer. Leaps performed in series grew in height and length; pirouettes began slowly and sped up – did the dancers play with the music or vice versa? But there were downcast, sad scenes as well, and maybe they were closer to reality.

notes highlighted with an exclamation point, that were accurately aligned with the tones of the trumpet or used as a means to chase another dancer. Leaps performed in series grew in height and length; pirouettes began slowly and sped up – did the dancers play with the music or vice versa? But there were downcast, sad scenes as well, and maybe they were closer to reality.

Of the two leading couples, Anna Ol and Artur Shesterikov melted jagged moves into soft ones; Aya Okumura and Young Gyo Choi flicked into their pas de deux like horses out of the bay at a race, before delivering some grandiose lifts, which included Okumura being propelled stunningly through the air. Later, Shesterikov prevented Ol from seeing something horrible – which

wasn’t revealed – before all four soloists performed together, weighed down by an unknown grief.

wasn’t revealed – before all four soloists performed together, weighed down by an unknown grief.

Red objects, among them hammer, sickle and stars, hung in front of the dark blue backdrop. Later, they were gradually raised. On the backdrop, a black arrowhead with a blurred edge could be seen diagonally upwards. (Maybe the first Sputnik veiled in dark clouds, flying through a cosmos of fragments of Communist Russia?) The arrowhead later turned into a black triangle.

In the final scene three women each were carried out by their partners to the left and right wings. Their diagonal lines reminded one of merrily flying flags. At the front of the stage, the two leading couples posed like victors.

In the final scene three women each were carried out by their partners to the left and right wings. Their diagonal lines reminded one of merrily flying flags. At the front of the stage, the two leading couples posed like victors.

The applause was thunderous. My enthusiasm was subdued, but only because of Ratmansky: he had made the tragedy and sadness pervading Shostakovich’s life palpable.

Matthew Rowe conducted Het Balletorkest. The piano soloist for Piano Concerto No. 1 was Michael Mouratch; Erwin ter Bogt played the trumpet.

Aya Okumura was promoted to soloist after the performance.

| Links: | Website of Dutch National Ballet | |

| Trailer “Shostakovich Trilogy” | ||

| Rehearsal “Shostakovich Trilogy” (Symphony No. 9), video | ||

| Rehearsal “Shostakovich Trilogy” (String Quartet No. 8), video | ||

| Photos: | Symphony No. 9 | |

| 1. | Ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 2. | Erica Horwood, Maria Chugai and ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 3. | Edo Wijnen, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 4. | Sho Yamada, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 5. | Suzanna Kaic, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 6. | Jozef Varga, Igone de Jongh, Sho Yamada and ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 7. | Ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 8. | Erica Horwood, Saya Okubo and ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| String Quartet No. 8 | ||

| 9. | Daniel Camargo, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 10. | Ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 11. | Sasha Mukhamedov, Daniel Camargo, Emanouela Merdjanova and Naira Agvanean, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 12. | Sasha Mukhamedov, Daniel Camargo and ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 13. | Daniel Camargo and ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 14. | Roman Artyushkin, Jared Wright, Skyler Martin, Martin ten Kortenaar and Daniel Camargo, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| Piano Concerto No. 1 | ||

| 15. | Aya Okumura, Young Gyu Choi and ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 16. | Aya Okumura and ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 17. | Aya Okumura and ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 18. | Artur Shesterikov and Anna Ol, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 19. | Artur Shesterikov and Anna Ol, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 20. | Anna Ol and ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| 21. | Ensemble, “Shostakovich Trilogy” by Alexei Ratmansky, Dutch National Ballet 2017 | |

| all photos © Hans Gerritsen | ||

| Editing: | Jake Stepansky |