“Woke up Blind”, “The Statement”, “The missing door”, “Safe as Houses”

Nederlands Dans Theater / NDT 1

Haus der Berliner Festspiele

Berlin, Germany

December 01, 2017

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2017 by Ilona Landgraf

The last programs I saw of Nederlands Dans Theater’s main company (NDT I) were rather drab. However, the program they presented during their guest appearance in Berlin turned out to be varied and meaty. Its four pieces were by the Argentinian choreographer Gabriela Carrizo, the company’s associate choreographers, Crystal Pite and Marco Goecke (each of them contributing one piece), and by the inseparable team of Sol León and artistic director Paul Lightfoot.

The last programs I saw of Nederlands Dans Theater’s main company (NDT I) were rather drab. However, the program they presented during their guest appearance in Berlin turned out to be varied and meaty. Its four pieces were by the Argentinian choreographer Gabriela Carrizo, the company’s associate choreographers, Crystal Pite and Marco Goecke (each of them contributing one piece), and by the inseparable team of Sol León and artistic director Paul Lightfoot.

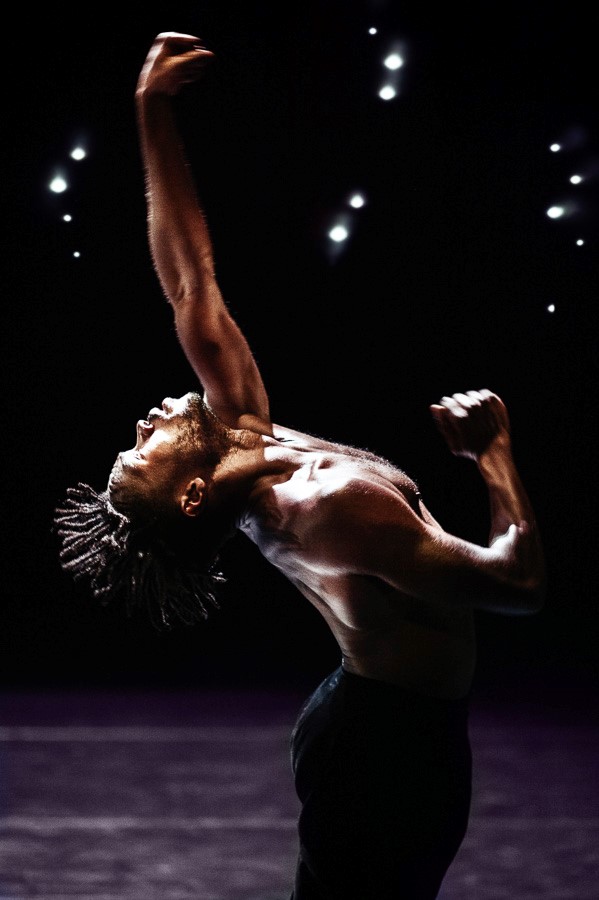

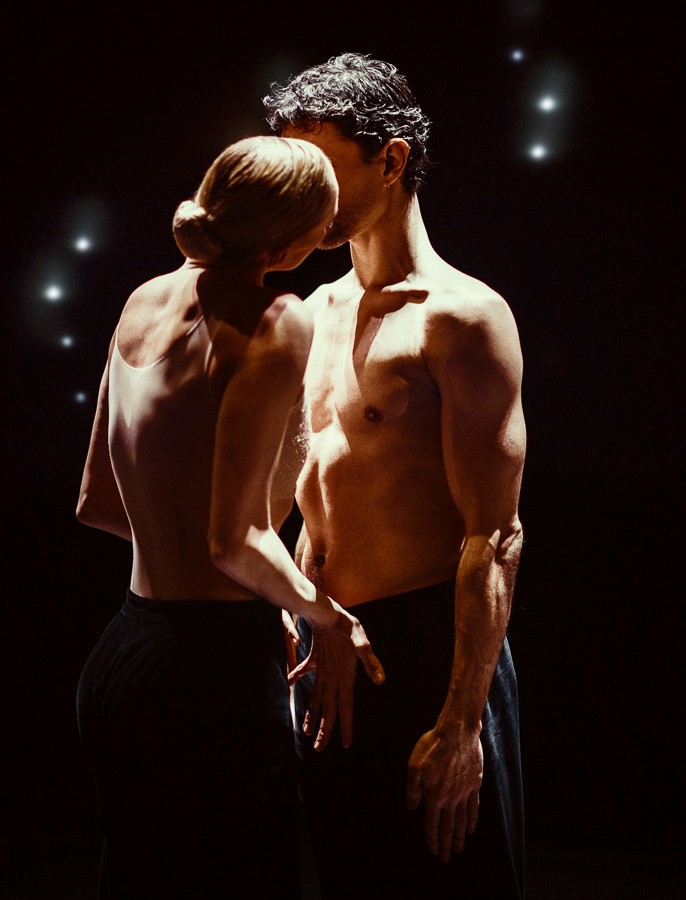

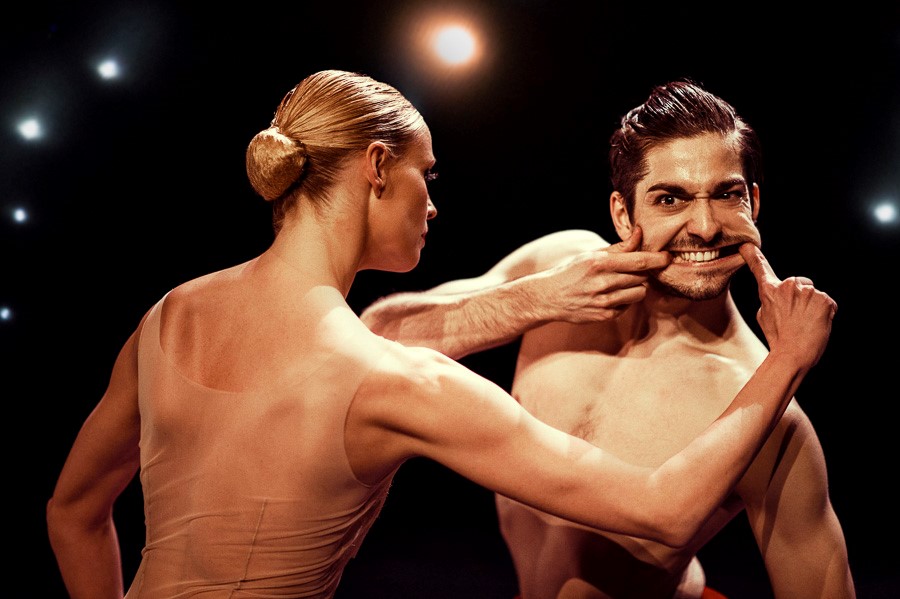

Goecke’s “Woke up Blind” opened the program. Its choreography was made for NDT 1 in 2016, involves seven dancers – two female, five male, and is set to music by the American singer-songwriter Jeff Buckley who tragically drowned at the age of thirty. Buckley’s two songs, “You and I” and “The Way Young Lovers Do”, talked more of romance than did Goecke’s

choreography. In one scene two men embraced and almost kissed each other, in another the couple was of mixed gender. But just when intimacy arose, other dancers slid on their feet onstage, joining the lovers and initiating a group dance scene.

choreography. In one scene two men embraced and almost kissed each other, in another the couple was of mixed gender. But just when intimacy arose, other dancers slid on their feet onstage, joining the lovers and initiating a group dance scene.

Goecke’s language is unique and even though I know his work, the physical power and ultra-precise body control his choreography demands still surprised me. It seemed beyond nature. Arms rowed through the air or jerked from one position to the other like the levers of a stiff machine. As arms and upper bodies were held in awkwardly crippled positions, suddenly

someone’s arm whipped so softly and quickly up and down that my eyes failed to follow it. Arms and hands darted sharply down like turbo-fast cleavers on a chopping board or pushed up and down as if they were scrubbing with crazy intensity a bottle’s neck with a dish scrubber. One dancer’s hands fidgeted hectically over his chest. Was he hysterical about insects crawling on his skin? One moment later he walked around onstage markedly nonchalant. Chests thrust forward and back, legs moved with lightning speed through single, precise grand battements or jumped unexpectedly from a standing position. Leaps were scarce and sharply contoured. As in Goecke’s other pieces the dancers sometimes hissed and growled like predators. Sometimes, movements looked like ecstatic full-body masturbation.

someone’s arm whipped so softly and quickly up and down that my eyes failed to follow it. Arms and hands darted sharply down like turbo-fast cleavers on a chopping board or pushed up and down as if they were scrubbing with crazy intensity a bottle’s neck with a dish scrubber. One dancer’s hands fidgeted hectically over his chest. Was he hysterical about insects crawling on his skin? One moment later he walked around onstage markedly nonchalant. Chests thrust forward and back, legs moved with lightning speed through single, precise grand battements or jumped unexpectedly from a standing position. Leaps were scarce and sharply contoured. As in Goecke’s other pieces the dancers sometimes hissed and growled like predators. Sometimes, movements looked like ecstatic full-body masturbation.

As usual with his work the stage was dark and its depth unfathomable. One single dot of light was subsequently enlarged into a circle made of of light dots. Set and costumes were by Goecke. As in most of his works he generally limited his dancers’ outfits to black pants for men and women, worn with bare chests (men) or skin-colored tops (women). The few times dancers appeared in red pants, the color merely looked lascivious.

As usual with his work the stage was dark and its depth unfathomable. One single dot of light was subsequently enlarged into a circle made of of light dots. Set and costumes were by Goecke. As in most of his works he generally limited his dancers’ outfits to black pants for men and women, worn with bare chests (men) or skin-colored tops (women). The few times dancers appeared in red pants, the color merely looked lascivious.

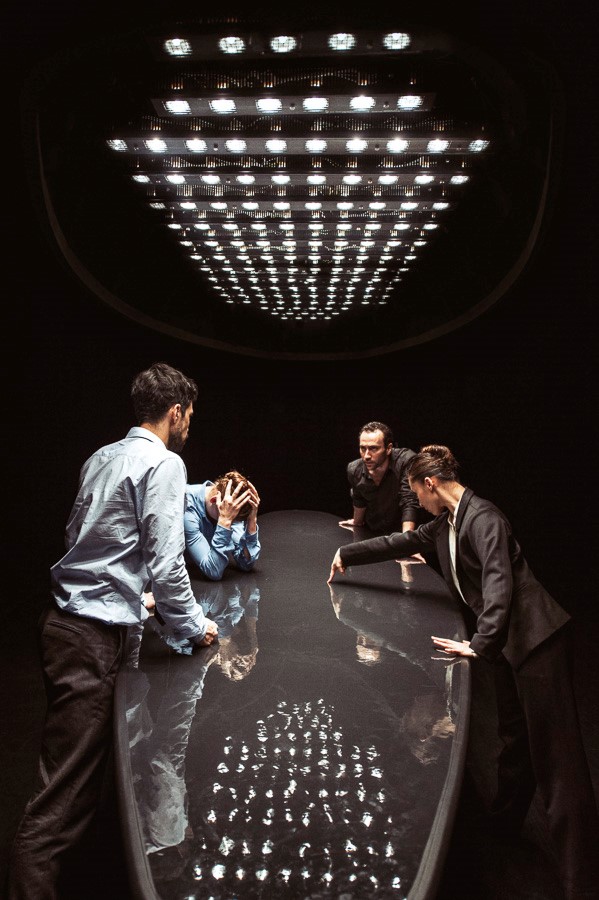

Pite’s “The Statement” surprised one from the start. The stage was gloomy. An oval metal conference table with thin legs stood center stage, sparsely lit by a huge black cylinder-shaped lamp hanging above it. Two women and two men in  business attire gathered around the table. The atmosphere of their meeting was tense and nervous. The situation seemed inescapable. Unlike in Kurt Jooss’s “The Green Table”, where the ten diplomats at the table toy with their power, in Pite’s piece the people in power were behind the scene. We never got to see them. They had delegated the quartet to give a statement about an escalating conflict abroad which the company had created and economically utilized. But no one wanted to take responsibility.

business attire gathered around the table. The atmosphere of their meeting was tense and nervous. The situation seemed inescapable. Unlike in Kurt Jooss’s “The Green Table”, where the ten diplomats at the table toy with their power, in Pite’s piece the people in power were behind the scene. We never got to see them. They had delegated the quartet to give a statement about an escalating conflict abroad which the company had created and economically utilized. But no one wanted to take responsibility.

The debate – a short play Pite wrote together with the playwright Jonathon Young – vacillated between agitation, accusations, self-justifications and blaming their bosses to calm their own nerves. We heard recorded voices talking at cross purposes,

their pitches pressured by strain; they whispered, murmured, and repeated empty comments: “No, it’s not our fault. […] We didn’t know the whole thing would blow up. […] How can your department act independently? […] That’s the language they use. […] The situation has changed. […] It’s all up to you. Fix it!” But the recording was only the bottom line of the many-faceted messages the bodies expressed. The debate was carried on by dance, not by talking. Movements were so startlingly trenchant, so absurdly exaggerated that they caused some laughs from the audience. Legs fidgeted nervously beyond the table; bottoms swung from one side to the other, heads lay down on the tabletop out of desperation, hands were wrung and stretched upwards in an impulse of praying.

their pitches pressured by strain; they whispered, murmured, and repeated empty comments: “No, it’s not our fault. […] We didn’t know the whole thing would blow up. […] How can your department act independently? […] That’s the language they use. […] The situation has changed. […] It’s all up to you. Fix it!” But the recording was only the bottom line of the many-faceted messages the bodies expressed. The debate was carried on by dance, not by talking. Movements were so startlingly trenchant, so absurdly exaggerated that they caused some laughs from the audience. Legs fidgeted nervously beyond the table; bottoms swung from one side to the other, heads lay down on the tabletop out of desperation, hands were wrung and stretched upwards in an impulse of praying.

Chloé Albaret and César Faria Fernandes’s characters dominated those of Aram Hasler and Spencer Dickhaus. The latter two held together, but at one point sat separately under the table like laboratory animals in a Skinner box, while Albaret and Fernandes faced each other on top of the table. Their talk was charged with erotic vibes and, although Albaret’s voice sounded like soft foam, she ultimately pulled the strings of power. Neither couple knew how to escape the dilemma. At the end, the cylindrical lamp lowered towards the table. “It’s gonna end,” was the last recorded comment. “The Statement” dates from 2016. It’s frighteningly close to reality.

Chloé Albaret and César Faria Fernandes’s characters dominated those of Aram Hasler and Spencer Dickhaus. The latter two held together, but at one point sat separately under the table like laboratory animals in a Skinner box, while Albaret and Fernandes faced each other on top of the table. Their talk was charged with erotic vibes and, although Albaret’s voice sounded like soft foam, she ultimately pulled the strings of power. Neither couple knew how to escape the dilemma. At the end, the cylindrical lamp lowered towards the table. “It’s gonna end,” was the last recorded comment. “The Statement” dates from 2016. It’s frighteningly close to reality.

Why Carrizo titled her dance theater piece “The missing door” wasn’t comprehensible. The set, a deep-stretched living room painted in the green of old copper roofs, had five doors and was open towards the right side. It provided – at least in theory – multiple variants for exits and entrances. But maybe the missing door, the title hints at, was the one leading out of the bizarre spine-chiller?

Why Carrizo titled her dance theater piece “The missing door” wasn’t comprehensible. The set, a deep-stretched living room painted in the green of old copper roofs, had five doors and was open towards the right side. It provided – at least in theory – multiple variants for exits and entrances. But maybe the missing door, the title hints at, was the one leading out of the bizarre spine-chiller?

When the curtain went up, a lifeless woman (Lydia Bustinduy) lay prone on the floor and in the corner of the room a man (Roger Van der Poel) lounged limply on a chair in front of a small work desk. Was he still in this world and just sleeping or already on the journey into the afterlife? Another man (Spencer Dickhaus) entered, dragged Bustinduy out across the floor, returned and started to wipe the floor with a cloth. But the cloth took on a life of its

own, swished around as if by magic and played cat-and-mouse with Dickhaus. Things were turning more and more weird. A chambermaid (Rena Narumi) positioned an armchair and a floor lamp on the left side of the room. Bustinduy took a seat and Van der Poel, suddenly awake, his hands bloody and trembling and his face struck by horror, embraced her. Why did he have blood on his hands? The embrace became a clutch and ended in a fight. Did Van der Poel re-experience a past story in his mind – a creepy and quite incongruent one?

own, swished around as if by magic and played cat-and-mouse with Dickhaus. Things were turning more and more weird. A chambermaid (Rena Narumi) positioned an armchair and a floor lamp on the left side of the room. Bustinduy took a seat and Van der Poel, suddenly awake, his hands bloody and trembling and his face struck by horror, embraced her. Why did he have blood on his hands? The embrace became a clutch and ended in a fight. Did Van der Poel re-experience a past story in his mind – a creepy and quite incongruent one?

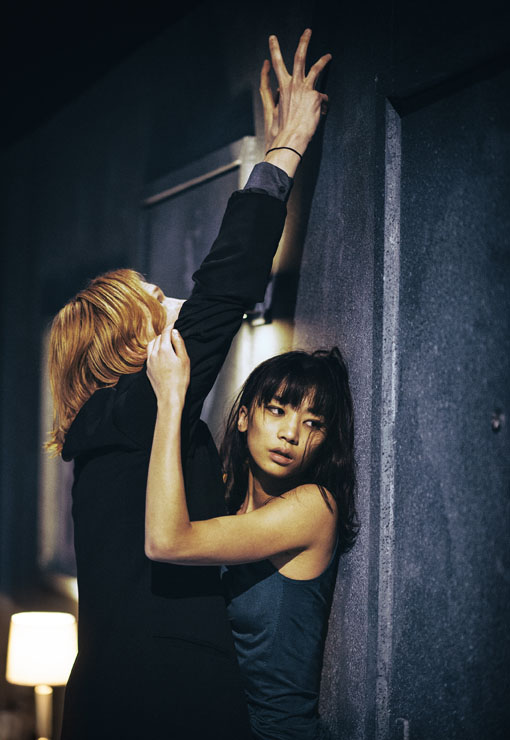

At one point of his flashback a red-haired man in a suit (Marne van Opstal) whirled a woman in a blue dress around (Meng-Ke Wu). She was as lifeless as a dummy and when she sat in the armchair she slid to the floor like a silk jersey would from a smooth leather seat. Later, Van Opstal crouched sobbingly in the corner of the room and still later, as he himself sat in the armchair, he laughed crazily and fell over together with the chair. From time to time an unknown man outside the room looked menacingly through the dusty window over the work desk.

At one point of his flashback a red-haired man in a suit (Marne van Opstal) whirled a woman in a blue dress around (Meng-Ke Wu). She was as lifeless as a dummy and when she sat in the armchair she slid to the floor like a silk jersey would from a smooth leather seat. Later, Van Opstal crouched sobbingly in the corner of the room and still later, as he himself sat in the armchair, he laughed crazily and fell over together with the chair. From time to time an unknown man outside the room looked menacingly through the dusty window over the work desk.

Some scenes were lit by an old-fashioned spotlight that was rolled in. A door couldn’t be unlocked no matter how much Van der Poel jiggled with the key, and eery knocking on another door made one’s blood run cold. When that door suddenly swung open, heavy blasts of air knocked everyone down. Sheets of newspaper were blown inside. A man (César Faria Fernandes) appeared in the doorway, using his arm like a machine gun or taser. Its rattling sounds

Some scenes were lit by an old-fashioned spotlight that was rolled in. A door couldn’t be unlocked no matter how much Van der Poel jiggled with the key, and eery knocking on another door made one’s blood run cold. When that door suddenly swung open, heavy blasts of air knocked everyone down. Sheets of newspaper were blown inside. A man (César Faria Fernandes) appeared in the doorway, using his arm like a machine gun or taser. Its rattling sounds  shook Van Opstal and Narumi as if they were convulsed by strong electric shocks. One piece of the wall broke loose and hung forward. The level of demolition was considerable.

shook Van Opstal and Narumi as if they were convulsed by strong electric shocks. One piece of the wall broke loose and hung forward. The level of demolition was considerable.

At the end the initial scene was repeated. Again, Van der Poel was seen lounging limply in his chair in front of the work desk; Dickhaus dragged Bustinduy out and fought with his wiping cloth. One hoped that Van der Poel would find the door to safety and escape his memory.

The sound scape of “The missing door” is by Raphaëlle Latini and is so sinister that it would do any thriller proud.

The first comment of my seated neighbor on León and Lightfoot’s “Safe as Houses” was whether the huge, black square made of sprigs that hung over the stage was a bird’s nest. If so, the bird must either have been giant-sized or a pterosaurian. But the stage didn’t hint at any fauna. Its backdrop and sides were light gray or off-white and the only set element was a white wall that rotated almost the entire time. The music by Johann Sebastian Bach was partly rearranged.

The first comment of my seated neighbor on León and Lightfoot’s “Safe as Houses” was whether the huge, black square made of sprigs that hung over the stage was a bird’s nest. If so, the bird must either have been giant-sized or a pterosaurian. But the stage didn’t hint at any fauna. Its backdrop and sides were light gray or off-white and the only set element was a white wall that rotated almost the entire time. The music by Johann Sebastian Bach was partly rearranged.

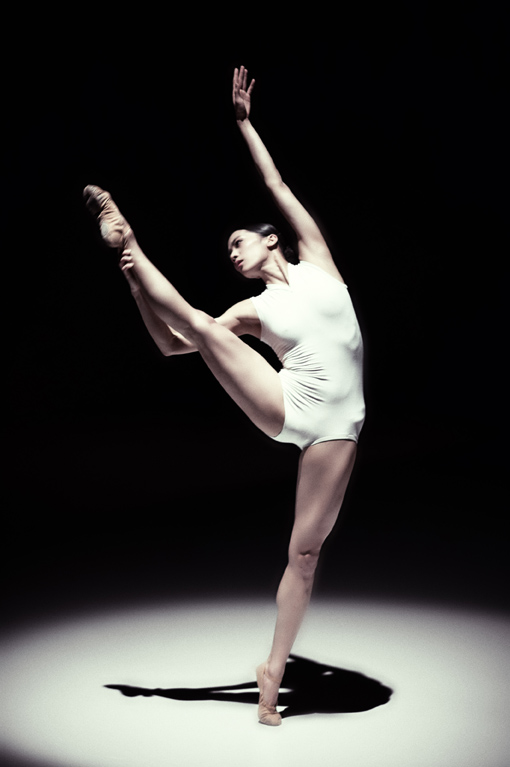

Compared to the preceding pieces, “Safe as Houses” was harmless and sent the audience home calmed. Its eleven dancers wore either simple black or white costumes. The ones in black performed first until a ballerina in a white leotard hopped from behind the wall and her companions, also in white, occupied the stage. Later, the rotating wall separated both groups. For some time the dancers in

black pushed the wall forward with their heads, while the dancers in white merely touched it as if it were the Wailing Wall. Solos and pas de deux were also danced outside the wall’s radius. León and Lightfoot blended classical and contemporary dance vocabulary. Movements looked broad and determined. I thought of Japanese characters interpreted through dance before reading in the program leaflet that the piece was inspired by the Chinese Book of Changes “I Ching”.

black pushed the wall forward with their heads, while the dancers in white merely touched it as if it were the Wailing Wall. Solos and pas de deux were also danced outside the wall’s radius. León and Lightfoot blended classical and contemporary dance vocabulary. Movements looked broad and determined. I thought of Japanese characters interpreted through dance before reading in the program leaflet that the piece was inspired by the Chinese Book of Changes “I Ching”.

In the last sequence two couples alternated in pas de deux to an adaption of “Komm, süßer Tod, komm, sel’ge Ruh”. The women split their legs in the air and sat on the men’s shoulders; the partners slid down against each other, then once again their bodies rose against the space. The music slowed down, the dance got lengthy, one wondered what would finally bring the wall to a halt and when blissful peace would occur. At the end Meng-Ke Wu, Olivier Coeffard and Prince Credell lined up in front of the closed curtain. They had been standing there at the beginning as well, facing away from the audience, and in their black suits were almost indiscernible from the curtain cloth. Now they stared towards the audience, sweating, panting and hardly sweetly dead.

In the last sequence two couples alternated in pas de deux to an adaption of “Komm, süßer Tod, komm, sel’ge Ruh”. The women split their legs in the air and sat on the men’s shoulders; the partners slid down against each other, then once again their bodies rose against the space. The music slowed down, the dance got lengthy, one wondered what would finally bring the wall to a halt and when blissful peace would occur. At the end Meng-Ke Wu, Olivier Coeffard and Prince Credell lined up in front of the closed curtain. They had been standing there at the beginning as well, facing away from the audience, and in their black suits were almost indiscernible from the curtain cloth. Now they stared towards the audience, sweating, panting and hardly sweetly dead.

Applause was intense and the dancers seemed glad.

| Links: | Website of Nederlands Dans Theater | |

| Website of the Haus der Berliner Festspiele | ||

| Trailer “Woke up Blind” | ||

| Trailer “The Statement” | ||

| Trailer “The missing door” | ||

| Trailer “Safe as Houses” | ||

| Photos: | The photos partly show a different cast from an earlier performance. The names of the dancers depicted weren’t provided. | |

| 1.-6. | Ensemble, “Woke up Blind” by Marco Goecke, Nederlands Dans Theater 2017 | |

| 7.-10. | Ensemble, “The Statement” by Crystal Pite, Nederlands Dans Theater 2017 | |

| 11.-18. | Ensemble, “The missing door” by Gabriela Carrizo, Nederlands Dans Theater 2017 | |

| 19.-25. | Ensemble, “Safe as Houses” by Sol León and Paul Lightfoot, Nederlands Dans Theater 2017 | |

| all photos © Rahi Rezvani | ||

| Editing: | Laurence Smelser |