Michael Meylac:

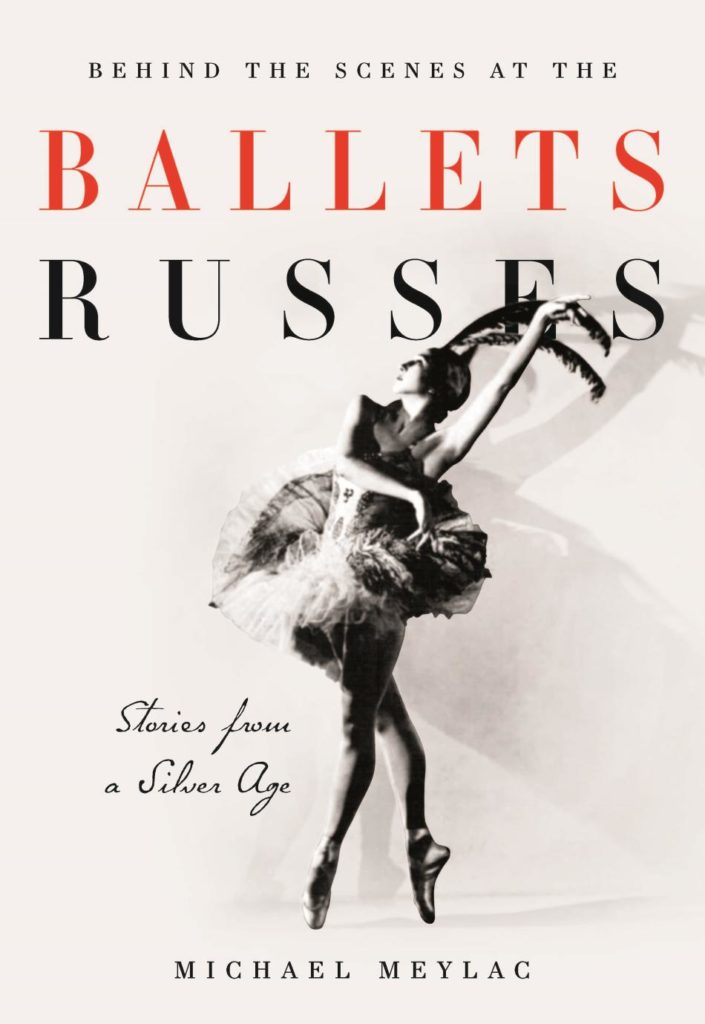

“Behind the Scenes at the Ballets Russes – Stories from a Silver Age”

288 pages, 78 b/w photos

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd., October 2017

ISBN: 9781780768595

January 2018

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2018 by Ilona Landgraf

Last year in early spring I met Michael Meylac at a performance of Cranko’s “Onegin” at the Bolshoi Theatre. Passionate about dance, Meylac quizzed me about the German companies and told me about the book on the Ballets Russes he was about to finish. He pondered which title to choose. We had no opportunity to continue our conversation, so I didn’t get to know more about the project.

Last year in early spring I met Michael Meylac at a performance of Cranko’s “Onegin” at the Bolshoi Theatre. Passionate about dance, Meylac quizzed me about the German companies and told me about the book on the Ballets Russes he was about to finish. He pondered which title to choose. We had no opportunity to continue our conversation, so I didn’t get to know more about the project.

Meanwhile, the book has been published.

Actually, I had expected a monograph on the Ballets Russes similar to Sjeng Scheijen’s biography of Diaghilev. I was wrong. “Behind the Scenes at the Ballets Russes” is a collection of interviews – thirty-two in total conducted between 1989 and 2007. Only one interviewee was not a dancer, the secretary of the Marquis de Cuevas; all others performed with the Ballet Russes companies.

Meylac, born in Leningrad, today’s St. Petersburg, is a distinguished Russian literature professor and philologist. Yet, the Soviet authorities disapproved of his work on foreign-published dissident writers and sentenced him to seven years imprisonment and five years in exile. In 1987, after four years in the Gulag, he was released and later settled in France. There he worked as a Professor of Russian Literature at the University of Strasbourg, sharing time between Europe and Russia.

When Meylac was introduced to Irina Baronova in London in 1989, he fortuitously recorded their conversation. This became the igniting spark for subsequent interviews. “In a sense, this book wrote itself almost as much as I wrote it: some encounters took place spontaneously, others I sought out, and often the first encounters led to more and more connections,” Meylac wrote in the preface. Many of his interview partners are Russian or come from families with Russian roots, but Meylac also talked with British-born Frederic Franklin (who danced under Massine with the Ballet Russe among others) and with the Frenchman Jean Babilée. Babilée’s crucial encounter with dance was a performance of “Les Sylphides” by the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, which he saw as a schoolboy.

In 2015 Meylac conducted a long interview with John Neumeier that is printed as the afterword. Neumeier, whom Meylac considers a “choreografo assoluto”, has been strongly influenced by Nijinsky and the Ballets Russes. The book is dedicated to him.

The history of the post-Diaghilev companies is knotty and full of vicissitudes. After the impresario’s death in 1929, Colonel de Basil and René Blum regathered a company in 1932 in Monaco. Their Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo later split into two rivaling troupes, one led by de Basil, the other by Blum. When in 1938 Blum’s company struggled financially, it was bought by Serge Denham who ensured its further existence for almost two decades. During World War II, de Basil’s and Denham’s troupes toured extensively, mainly in South and North America, but also in Australia. Often, dancers stayed behind after a tour and became directly involved in the formation and development of ballet in their respective countries. In the meantime, Sergei Lifar, Diaghilev’s former star dancer, founded the Nouveau Ballet de Monte Carlo in Monaco in 1945. Two years later it merged with the Ballet International du Marquis de Cuevas to the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas. This company gave its last performance in 1962, one year after the Marquis’s death.

Altogether, the interviews capture the often tumultuous ups and downs the various Ballets Russes companies went through. Especially interesting is what the conversations reveal about different personalities and life paths. Quite a few interviewees fled the Russian Revolution at a young age under dreadful circumstances. One-year-old Baronova, for example, had to lie stock-still on her stomach in the boat that brought her and her parents from Odessa to Romania. Had she cried the smuggler would have thrown her over-board. Marika Besobrasova and her family escaped the Red Army’s attack on the last English steamer that left Yalta. Having arrived in Constantinople, she nearly died of pneumonia and was saved by a Russian émigré surgeon at the last moment. Besobrasova later founded the Académie de Danse Classique Princesse Grace in Monte Carlo, where she trained many major dancers.

Paris was a hub for expatriate Russian dancers: Mathilda Kshessinska, Olga Preobrajenska and Lubov Egorova each maintained studios in Paris, and that’s where the young Balanchine spotted his three baby ballerinas: Tatiana Riabouchinska studied with Kshessinska, and Tamara Toumanova and Baronova with Preobrajenska. Meylac talked with all three of them.

Many of the dancers led a nomadic life either because faith washed them to other shores or they avoided World War II by touring remote countries. Their anecdotes and critical remarks, as well as the details they remembered of productions and performances, of their work with choreographers like Massine, Lifar, Nijinska, Lichine or Balanchine, chronicle dance history. Baronova, for example, recalled an incident with Fokine when touring Berlin. Hitler and his retinues were passing by along the street outside and the dancers rushed to the balcony to see them. Fokine lost his temper shouting: “How dare you walk out on Fokine’s rehearsal! … Fokine is more important than Hitler.” Then he left, slamming the door.

Naturally, opinions are divided, and a single truth doesn’t exist. While some considered Balanchine a great innovator and genius, for example, most disliked his American period. “He ruined American ballet … He repudiated the spiritual side of dance. He only left the technique and abstract ideas. And just think what he had choreographed before,” said Anatoly Joukowsky.

The vast majority of Meylac’s interviewees passed away soon after. Had he not preserved their memories in time, they would have been lost. We wouldn’t be able to learn about Lifar’s frightening encounter with Resistance fighters after a performance in Saint-Étienne, nor Alexandra Danilova’s story about Nicholas Legat, who experienced unpleasant side effects when he got a kidney transplant from an orangutan.

Meylac, possessing a stupendously detailed knowledge, occasionally supplements the conversations with condensed background information. Regardless of whose name is mentioned in the course of the discussion, he knows about their family, career and history. Ismene Brown contributed a crisp, eloquent foreword and highlighted another advantage, Meylac inherently has: he is Russian: “Some … interviews … could only have been conducted by a Russian questioner with Russian interviewees for Russian readers – between compatriots, lips could be unbuttoned, confidences shared, antagonisms aired and candid opinions given about rival dancers or impresarios.”

The lineage of dance is widely branched, but its network is tightly knit. Mutual influences have been maintained despite political borders. Even the Soviet Iron Curtain still had some holes and should rather have been called a permeable membrane, wrote Meylac. “The West in Russia” and “Russia in the West” is what interests him most. The second part is done; hopefully he has plans to tackle the first.

“Behind the Scenes at the Ballets Russes” is only an excerpt, translated from the original Russian edition which comes in two large volumes and includes sections about music, art, theater and cinema. A translation of the complete work would be highly welcome. Moreover, a digitized version with a detailed keyword index would be very useful to make the interviews accessible for future research.

| Links: | Website of I. B. Tauris / Publishing House | |

| Photo: | 1. | “Behind the Scenes at the Ballets Russes” by Michael Meylac, book cover (cover photo: Alexandra Danilova in “The Firebird” by Mikhail Fokine, 1940) © I.B.Tauris & Co |

| Editing: | Tiffany Lau |