“Spring Draft Works”

The Royal Ballet

Royal Opera House

London, Great Britain

May 14, April 2021 (online)

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2021 by Ilona Landgraf

It’s hard to imagine that the pandemic has had any positive impact on the performing arts – but, as Kevin O’Hare, the Royal Ballet’s ever-optimistic artistic director points out in his introductory comments on this season’s “Spring Draft Works” (an annual project that assembles choreographies created by the company’s dancers) – there’s a silver lining: more free time to unlock hidden choreographic potential and rehearse, and the chance to include live music. Even the renowned lighting designer Natasha Chivers had time to create clever lighting tailored to each piece.

It’s hard to imagine that the pandemic has had any positive impact on the performing arts – but, as Kevin O’Hare, the Royal Ballet’s ever-optimistic artistic director points out in his introductory comments on this season’s “Spring Draft Works” (an annual project that assembles choreographies created by the company’s dancers) – there’s a silver lining: more free time to unlock hidden choreographic potential and rehearse, and the chance to include live music. Even the renowned lighting designer Natasha Chivers had time to create clever lighting tailored to each piece.

This year’s program consisted of twelve short pieces by nine choreographers – some novices, others old hands. Each choreographer introduced their work in a brief statement. Notably (and gratefully), no one used “Spring Draft Works” as an outlet for pandemic-related artistic desperation – which I’ve seen enough elsewhere.

Joshua Junker contributed no less than three pieces: one group dance, a pas de deux, and a solo.

Joshua Junker contributed no less than three pieces: one group dance, a pas de deux, and a solo.

In the “The Morning Routine”, we watch one man (danced by Junker, presumably depicting a choreographer) wake up, take a shower, head to the studio, and work with five dancers on a new piece. The choreography he invents is fluent and heavily features arm movements. In the opening scene, the dancers and Junker run and gesture agitatedly, like sailors fighting against a (creative?) storm. Later, they move in slow motion, both walking and flying as if on the moon. At several moments, the dancers approach Junker almost aggressively, as if demanding instructions. Junker wavers between confidence – or, at least, the

appearance of confidence – and doubt. Once, he stands crumpled and crouched (reminiscent of a snail retracted into its shell) before suddenly pulling himself out of his pondering, straightening up, and launching his limbs out into space.

appearance of confidence – and doubt. Once, he stands crumpled and crouched (reminiscent of a snail retracted into its shell) before suddenly pulling himself out of his pondering, straightening up, and launching his limbs out into space.

The score was composed by Bas Ibellini and transforms the sounds that Junker usually makes when improvising dance into music. It lends some scenes a humorous note.

In his pas de deux “Two Seasons”, Junker dances with Ashley Dean to a recomposition of Vivaldi’s “The Four Seasons – Spring 2” by Max Richter. Again, Junker contrasts fluid movements with edgy, jerky ones: hunched shoulders, frantically fluttering hands, and rectangularly-locked arms. The dancers respond to each other’s movements and gazes like magnetic fields. At one point, they swing their arms energetically, seemingly symbolizing a play for power and dominance that ultimately concludes in trustful togetherness.

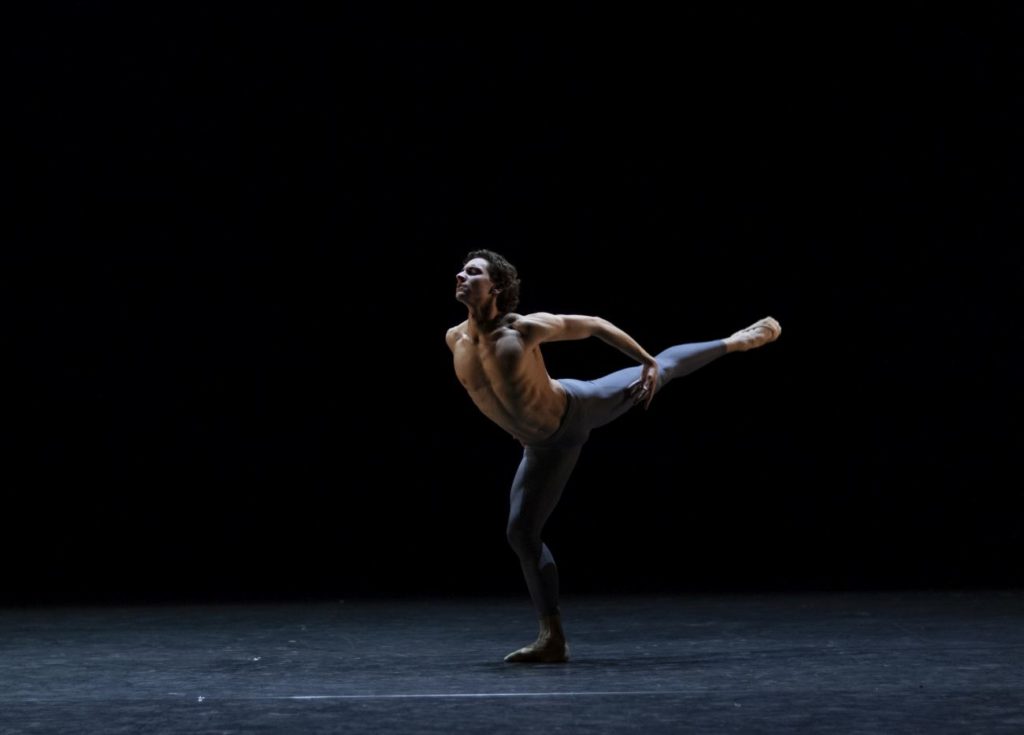

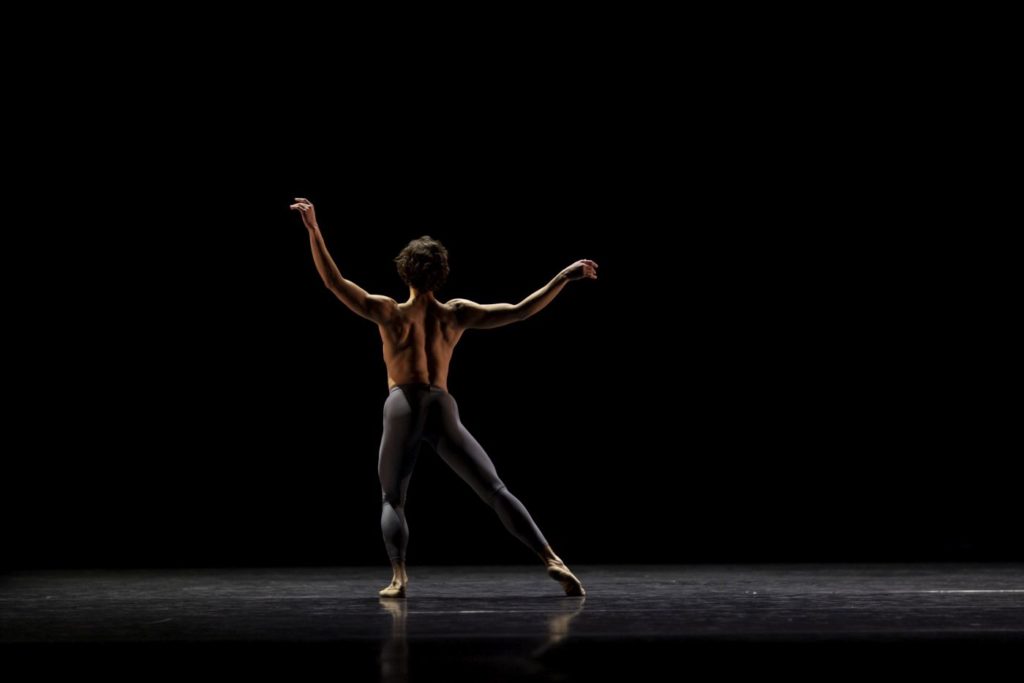

Junker’s third piece, the solo “324a”, reminds me of a study on the features of an ideal man. “Ideal” is relative, though, and the man (danced by Giacomo Rovero) in all likelihood represents the ideals of long ago. Fittingly, Junker chose music by Bach. His solo combines virility and power with rounded softness, and sharp perfection with fleet-footed-ness. Rovero reins in his jumps – there’s no need to show off his prowess, as his inner balance generates an external poise.

Junker’s third piece, the solo “324a”, reminds me of a study on the features of an ideal man. “Ideal” is relative, though, and the man (danced by Giacomo Rovero) in all likelihood represents the ideals of long ago. Fittingly, Junker chose music by Bach. His solo combines virility and power with rounded softness, and sharp perfection with fleet-footed-ness. Rovero reins in his jumps – there’s no need to show off his prowess, as his inner balance generates an external poise.

For Valentino Zucchetti, the “Draft Works” platform has been an outlet for his choreographic creativity for a decade. This year, he contributed two pieces, a solo and a pas de deux; both times he put the ballerina in pointe shoes. (Marcelino Sambé, whose piece is described below, was the only other choreographer using pointe shoes.) As he did ten

For Valentino Zucchetti, the “Draft Works” platform has been an outlet for his choreographic creativity for a decade. This year, he contributed two pieces, a solo and a pas de deux; both times he put the ballerina in pointe shoes. (Marcelino Sambé, whose piece is described below, was the only other choreographer using pointe shoes.) As he did ten  years ago, Zucchetti choreographed for Yasmine Naghdi in the solo “Inner” to music by Mozart. Watching Naghdi in her natty red dress made me think about how much freedom and satisfaction dancing engenders, especially when one has the stage to themself. Zucchetti’s choreography is energetic and intense; it breathes life. At the end, Naghdi runs towards the wings and lets herself fall backwards, safely caught by invisible hands.

years ago, Zucchetti choreographed for Yasmine Naghdi in the solo “Inner” to music by Mozart. Watching Naghdi in her natty red dress made me think about how much freedom and satisfaction dancing engenders, especially when one has the stage to themself. Zucchetti’s choreography is energetic and intense; it breathes life. At the end, Naghdi runs towards the wings and lets herself fall backwards, safely caught by invisible hands.

The second piece, “Outwardly Finds,” (music by Rachmaninoff) is, as Zucchetti describes it, “situated in the moment you reach out for companionship after having been on your own for such a long time.” He compares it to the moment when two lost souls find one another, whereupon their inner turmoil eases. Mariko Sasaki and Lukas Bjørneboe Brændsrød depicted

this couple. Initially, both dance alone, mirroring each other’s movements (perhaps subconsciously). Once they’ve met, their encounter soon turns from cautious acquaintance-making to playful gymnastics. As their mutual affection deepens, their dance becomes more and more sensitive. Even when dancing apart, they seem to be closely connected by invisible ties. Sasaki enjoys being close to Brændsrød, and he doesn’t need to watch her dance to match her movements. Their many lifts underscore the relationship’s lightness and intimacy.

this couple. Initially, both dance alone, mirroring each other’s movements (perhaps subconsciously). Once they’ve met, their encounter soon turns from cautious acquaintance-making to playful gymnastics. As their mutual affection deepens, their dance becomes more and more sensitive. Even when dancing apart, they seem to be closely connected by invisible ties. Sasaki enjoys being close to Brændsrød, and he doesn’t need to watch her dance to match her movements. Their many lifts underscore the relationship’s lightness and intimacy.

South African-born Ashley Dean wanted to celebrate the wide variety of dance movements from different African cultures she grew up in. In her piece “Nyakaza” – roughly meaning “to groove” – two women (Mica Bradbury and Hannah Grennell) weave choppy robot-like movements into a flowing core of limber, easygoing contemporary dance. They alternate between soft movements – undulations that run through the entire body, hip swings, and supple knee-bounces – and jerky, isolated movements. They twist and turn their ankles, click their lower arms into edgy positions, and pull their shoulders up to their ears, from where they suddenly mold into a classic ballet pose. The music – “Saint Saens – Groove Mix” – is by Mooryc and fuels their appetite to dance.

South African-born Ashley Dean wanted to celebrate the wide variety of dance movements from different African cultures she grew up in. In her piece “Nyakaza” – roughly meaning “to groove” – two women (Mica Bradbury and Hannah Grennell) weave choppy robot-like movements into a flowing core of limber, easygoing contemporary dance. They alternate between soft movements – undulations that run through the entire body, hip swings, and supple knee-bounces – and jerky, isolated movements. They twist and turn their ankles, click their lower arms into edgy positions, and pull their shoulders up to their ears, from where they suddenly mold into a classic ballet pose. The music – “Saint Saens – Groove Mix” – is by Mooryc and fuels their appetite to dance.

With “Memento”, Stanislaw Wegrzyn aims to remind people to do the things they love in life more often. The piece has two parts; the first is about “all living beings on earth,” as Wegrzyn vaguely explains. Sumina Sasaki and Marco Masciari stretch their arms into space, thrust their heads downwards, and sleekly (and somewhat effusively) glide through a duet that doesn’t make its theme explicitly evident. The second part is marked by a change in

With “Memento”, Stanislaw Wegrzyn aims to remind people to do the things they love in life more often. The piece has two parts; the first is about “all living beings on earth,” as Wegrzyn vaguely explains. Sumina Sasaki and Marco Masciari stretch their arms into space, thrust their heads downwards, and sleekly (and somewhat effusively) glide through a duet that doesn’t make its theme explicitly evident. The second part is marked by a change in

lighting from golden to blue. Wegrzyn suggests that this section has a spiritual quality to it, and to achieve this intended transcendence, he has chosen the ideal dancer: Edward Watson. The seasoned Watson dominates the stage like a Titan. At one point, he reminded me of Nijinsky in “Sheherazade”. Watson shimmers with a beauty that isn’t sweet and pleasing, but rather deep. He is subsequently joined by Sasaki and Masciari, who pull him back to the front as he attempts to retreat, and push him forward as he lies back onto their backs. In the end, Watson walks off, his silhouette fading in the darkness while Sasaki and Masciari unwaveringly continue to dance.

lighting from golden to blue. Wegrzyn suggests that this section has a spiritual quality to it, and to achieve this intended transcendence, he has chosen the ideal dancer: Edward Watson. The seasoned Watson dominates the stage like a Titan. At one point, he reminded me of Nijinsky in “Sheherazade”. Watson shimmers with a beauty that isn’t sweet and pleasing, but rather deep. He is subsequently joined by Sasaki and Masciari, who pull him back to the front as he attempts to retreat, and push him forward as he lies back onto their backs. In the end, Watson walks off, his silhouette fading in the darkness while Sasaki and Masciari unwaveringly continue to dance.

“Morphean” by Amelia Townsend is about sleep, insomnia, and how dreams are created in our minds. The music, composed by Cameron Buckmaster, opens with a voice asking: “Do you control the dream?” to which three women respond by holding the head and shoulders of a fourth. All of them have tightly braided hair. To soft, repetitive techno sounds and an ongoing monologue about dreams, the women perform group sequences, breaking away into solos that entail responding to every beat with sharp or slack movements. At the end, another one of the four gets hauled off by her peers.

“Morphean” by Amelia Townsend is about sleep, insomnia, and how dreams are created in our minds. The music, composed by Cameron Buckmaster, opens with a voice asking: “Do you control the dream?” to which three women respond by holding the head and shoulders of a fourth. All of them have tightly braided hair. To soft, repetitive techno sounds and an ongoing monologue about dreams, the women perform group sequences, breaking away into solos that entail responding to every beat with sharp or slack movements. At the end, another one of the four gets hauled off by her peers.

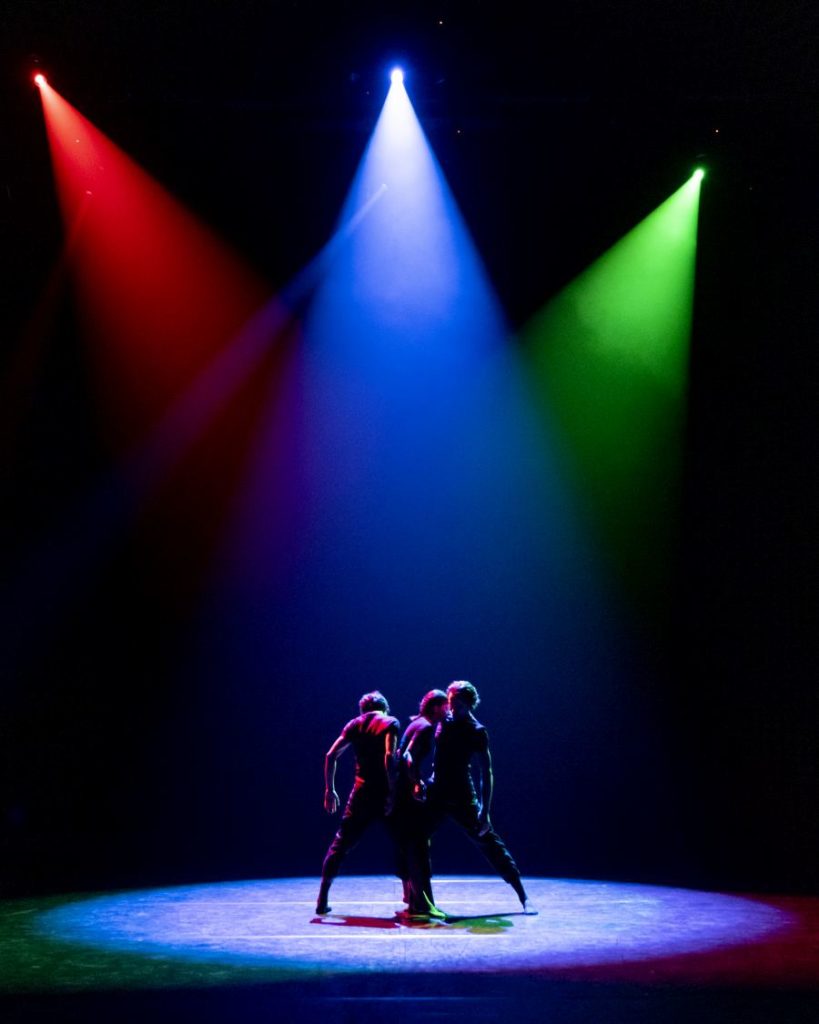

While speaking about his piece “Waveform,” Matthew Ball admits that he has missed live music in his daily life during lockdown and wanted to explore how we hear music and what distinguishes its color, timbre, and instrumentation. He goes so far as to explore the math and fractions of sound, and how its harmony and geometry result in atmospheric energy. His musical research object was Dvořák’s “Poco Adagio from Piano Trio No. 4,” and his team of dance interpreters consisted of Mayara Magri, Luca Acri, and Ball himself. In the opening scene, Acri and Ball lie head-to-head on the floor, stabilizing Magri, who stands above their heads. To single piano tones, she leans backwards and forwards like the hand of a huge clock. Later, the two men lift Magri by her shoulders so that her legs, held in diamond shape, swing to either side like a pendulum.

While speaking about his piece “Waveform,” Matthew Ball admits that he has missed live music in his daily life during lockdown and wanted to explore how we hear music and what distinguishes its color, timbre, and instrumentation. He goes so far as to explore the math and fractions of sound, and how its harmony and geometry result in atmospheric energy. His musical research object was Dvořák’s “Poco Adagio from Piano Trio No. 4,” and his team of dance interpreters consisted of Mayara Magri, Luca Acri, and Ball himself. In the opening scene, Acri and Ball lie head-to-head on the floor, stabilizing Magri, who stands above their heads. To single piano tones, she leans backwards and forwards like the hand of a huge clock. Later, the two men lift Magri by her shoulders so that her legs, held in diamond shape, swing to either side like a pendulum.

Interesting trio-groupings recur throughout. In one, the three stand in a tandem-line, forming different geometrical structures with their outstretched arms. In another, again in tandem-line, they change positions by diving through the others’ legs or by lifting one another overhead as if a stationary organism in perpetual transition. Standing in a line, they push each other’s hips like the pendulums in a Newton’s cradle or resist the pull generated by one leaning away from the others. Solos, couples, and group dances alternate seamlessly. The atmosphere, initially serene, turns livelier as the floor is lit like a watery surface dotted with spots of colorful light. The dancers’ exit is electric, Acri and Ball carrying Magri above their heads.

Interesting trio-groupings recur throughout. In one, the three stand in a tandem-line, forming different geometrical structures with their outstretched arms. In another, again in tandem-line, they change positions by diving through the others’ legs or by lifting one another overhead as if a stationary organism in perpetual transition. Standing in a line, they push each other’s hips like the pendulums in a Newton’s cradle or resist the pull generated by one leaning away from the others. Solos, couples, and group dances alternate seamlessly. The atmosphere, initially serene, turns livelier as the floor is lit like a watery surface dotted with spots of colorful light. The dancers’ exit is electric, Acri and Ball carrying Magri above their heads.

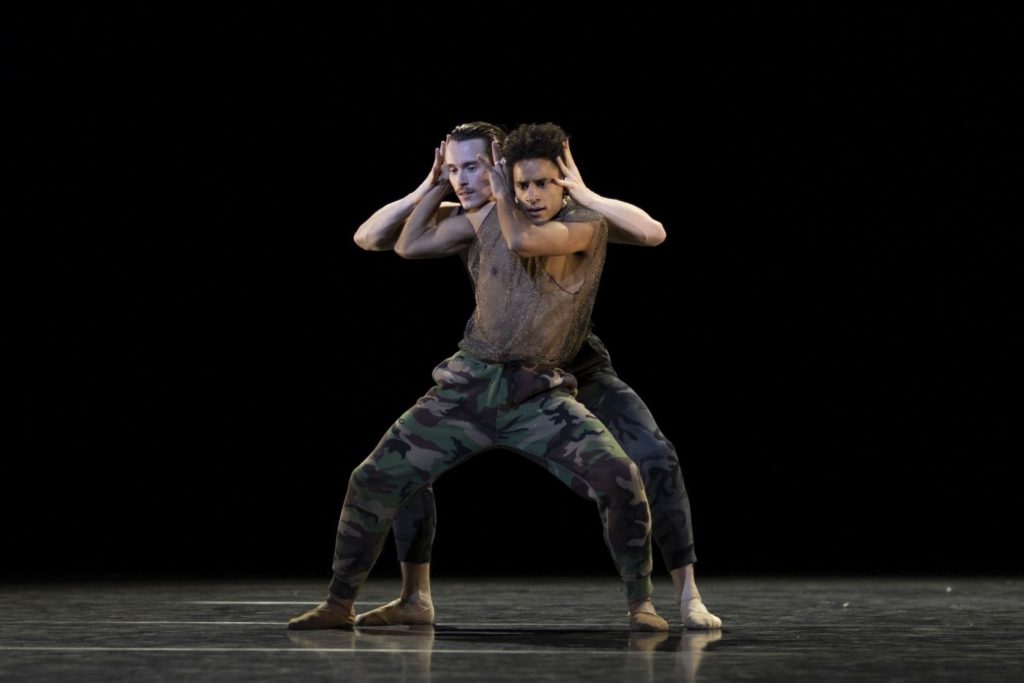

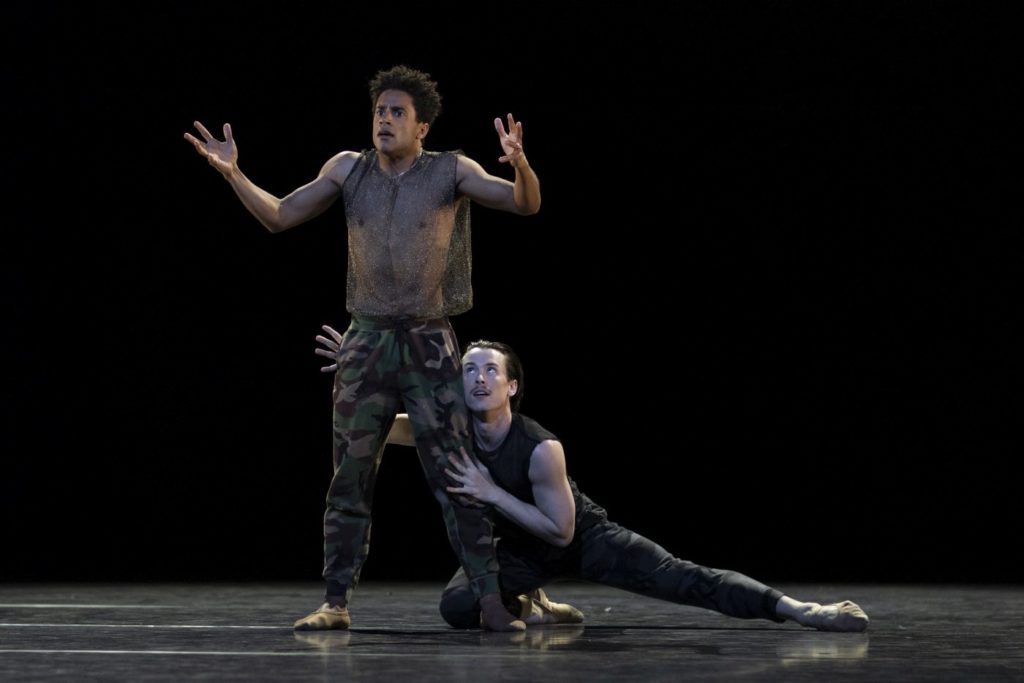

Marcelino Sambé transformed the themes of Shakespeare’s “Othello,” – speed, wits, aggression, suspicion, and multi-layered character – into movement. “Othello’s Limbo” is the title of his piece (set to music by Nico Muhly); he took the role of Othello for himself. Calvin Richardson danced the sinister Iago, who perpetually manipulates Othello’s moves, thoughts, and stance. He grinds his teeth like a beast of prey before smoothing his

Marcelino Sambé transformed the themes of Shakespeare’s “Othello,” – speed, wits, aggression, suspicion, and multi-layered character – into movement. “Othello’s Limbo” is the title of his piece (set to music by Nico Muhly); he took the role of Othello for himself. Calvin Richardson danced the sinister Iago, who perpetually manipulates Othello’s moves, thoughts, and stance. He grinds his teeth like a beast of prey before smoothing his

facial features with his hands and putting on the mask of slick friendship once again. Othello, totally confused, shakes off Iago once but, eaten up by doubt and jealousy, finally succumbs to his cynical puppet play. Madison Bailey portrayed the guiltless Desdemona, who is wrongly accused of having an affair with Cassio (Denilson Almeida).

facial features with his hands and putting on the mask of slick friendship once again. Othello, totally confused, shakes off Iago once but, eaten up by doubt and jealousy, finally succumbs to his cynical puppet play. Madison Bailey portrayed the guiltless Desdemona, who is wrongly accused of having an affair with Cassio (Denilson Almeida).

Sambé condensed the drama into forceful, emotionally-charged choreography.

“… And At The Hour of Death” is about the journey of life, explains choreographer Benjamin Ella. At the start of this journey, a bare-chested, lonely man (Harry Churches) slowly walks onstage, having a very bad day. His hands run over his exhausted face as he sinks down on all fours, shoulders crouched. He is joined by five men who take heavy steps with hunched backs. One after the other, the men lie down on the floor as if about to sleep, rising briefly only to sink back again. In the murky lighting, their gray outfits almost merge with the ground. Later, they fight (against what?), their fists clenched, holding their heads as if preparing for an explosion. Their space-consuming jumping is quickly replaced by stooped slouching; everyone who steps outside the sharply defined circle of light looks lost.

“… And At The Hour of Death” is about the journey of life, explains choreographer Benjamin Ella. At the start of this journey, a bare-chested, lonely man (Harry Churches) slowly walks onstage, having a very bad day. His hands run over his exhausted face as he sinks down on all fours, shoulders crouched. He is joined by five men who take heavy steps with hunched backs. One after the other, the men lie down on the floor as if about to sleep, rising briefly only to sink back again. In the murky lighting, their gray outfits almost merge with the ground. Later, they fight (against what?), their fists clenched, holding their heads as if preparing for an explosion. Their space-consuming jumping is quickly replaced by stooped slouching; everyone who steps outside the sharply defined circle of light looks lost.

Towards the end, as the music changes from electronic sound to even-tempered piano music by Bach, the men dance unconnected solos while moving together towards the right side of the stage. Only one stays behind, desperately trying to get something out of the last moment of life. Behind him, the horizontal strip-light lowers mercilessly until it’s completely dark.

Towards the end, as the music changes from electronic sound to even-tempered piano music by Bach, the men dance unconnected solos while moving together towards the right side of the stage. Only one stays behind, desperately trying to get something out of the last moment of life. Behind him, the horizontal strip-light lowers mercilessly until it’s completely dark.

Kristen McNally took her inspiration from Quentin Tarantino’s “Pulp Fiction” – specifically from the twist contest that takes place at Jack Rabbit Slim’s restaurant. In her “Le Temps L’amour”, fittingly accompanied by 60s pop songs by female French artists, six dancers seated at small tables depict a quirky audience, bored-ly sipping cocktails and beer, before venturing center stage for a solo or duet. The sturdy, gray-haired Phillip Mosley, spiffed up in a glitzy golden vest, plays the MC, assisted by a bespectacled lad (in the film, the assistant is a Marilyn Monroe lookalike), with whom he munches sandwiches in between acts. The show ends when Mosley slips into his green jacket and leaves, dragging his moveable shopper behind him.

| Links: | Website of the Royal Ballet | |

| Photos: | “The Morning Routine” by Joshua Junker | |

| 1. | Joshua Junker, Isabel Lubach, Francisco Serrano, Isabella Gasparini, Kristen McNally, and Téo Dubreuil, “The Morning Routine” by Joshua Junker, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 2. | Joshua Junker, Isabel Lubach, Francisco Serrano, Isabella Gasparini, Kristen McNally, and Téo Dubreuil, “The Morning Routine” by Joshua Junker, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 3. | Joshua Junker, Isabel Lubach, Francisco Serrano, Isabella Gasparini, Kristen McNally, and Téo Dubreuil, “The Morning Routine” by Joshua Junker, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 4. | Joshua Junker, Isabel Lubach, Francisco Serrano, Isabella Gasparini, Kristen McNally, and Téo Dubreuil, “The Morning Routine” by Joshua Junker, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| “324a” by Joshua Junker |

||

| 5. | Giacomo Rovero, “324a” by Joshua Junker, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 6. | Giacomo Rovero, “324a” by Joshua Junker, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| “Inner” by Valentino Zucchetti |

||

| 7. | Yasmine Naghdi, “Inner” by Valentino Zucchetti, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 8. | Yasmine Naghdi, “Inner” by Valentino Zucchetti, The Royal Ballet 2021 |

|

| 9. | Yasmine Naghdi, “Inner” by Valentino Zucchetti, The Royal Ballet 2021 |

|

| “Outwardly Finds” by Valentino Zucchetti |

||

| 10. | Mariko Sasaki and Lukas Bjørneboe Brændsrød, “ Outwardly Finds” by Valentino Zucchetti, The Royal Ballet 2021 |

|

| 11. | Lukas Bjørneboe Brændsrød and Mariko Sasaki, “ Outwardly Finds” by Valentino Zucchetti, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| “Nyakaza” by Ashley Dean |

||

| 12. | Mica Bradbury and Hannah Grennell, “Nyakaza” by Ashley Dean, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 13. | Hannah Grennell and Mica Bradbury, “Nyakaza” by Ashley Dean, The Royal Ballet 2021 |

|

| “Memento” by Stanislaw Wegrzyn |

||

| 14. | Sumina Sasaki and Marco Masciari, “Memento” by Stanislaw Wegrzyn, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 15. | Marco Masciari and Sumina Sasaki, “Memento” by Stanislaw Wegrzyn, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 16. | Sumina Sasaki, Marco Masciari, and Edward Watson, “Memento” by Stanislaw Wegrzyn, The Royal Ballet 2021 |

|

| 17. | Edward Watson, “Memento” by Stanislaw Wegrzyn, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| “Morphean” by Amelia Townsend | ||

| 18. | Leticia Dias, Charlotte Tonkinson, Amelia Townsend, and Marianna Tsembenhoi, “Morphean” by Amelia Townsend, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 19. | Leticia Dias, Marianna Tsembenhoi, Charlotte Tonkinson, and Amelia Townsend, “Morphean” by Amelia Townsend, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| “Waveform” by Matthew Ball | ||

| 20. | Mayara Magri, Luca Acri, and Matthew Ball, “Waveform” by Matthew Ball, The Royal Ballet 2021 |

|

| 21. | Matthew Ball, Mayara Magri, and Luca Acri, “Waveform” by Matthew Ball, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 22. | Mayara Magri, Luca Acri, and Matthew Ball, “Waveform” by Matthew Ball, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| “Othello’s Limbo” by Marcelino Sambé | ||

| 23. | Calvin Richardson (Iago) and Marcelino Sambé (Othello), “Othello’s Limbo” by Marcelino Sambé, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 24. | Madison Bailey (Desdemona), and Marcelino Sambé (Othello), “Othello’s Limbo” by Marcelino Sambé, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 25. | Marcelino Sambé (Othello) and Calvin Richardson (Iago), “Othello’s Limbo” by Marcelino Sambé, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 26. | Madison Bailey (Desdemona), and Marcelino Sambé (Othello), “Othello’s Limbo” by Marcelino Sambé, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| “…And At The Hour Of Death” by Benjamin Ella | ||

| 27. | Liam Boswell, “…And At The Hour Of Death” by Benjamin Ella, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 28. | Brayden Gallucci, “…And At The Hour Of Death” by Benjamin Ella, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 29. | David Donnelly, “…And At The Hour Of Death” by Benjamin Ella, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| “Le Temps L’amour” by Kristen McNally (no photos available) | ||

| all photos © Andrej Uspenski | ||

| Editing: | Jake Stepansky |