“Wayfarers”

Stuttgart Ballet

Stuttgart State Opera

Stuttgart, Germany

April 25, 2014

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2014 by Ilona Landgraf

Stuttgart Ballet’s innovative energy seems unstoppable. Some days ago this season’s third premiere, “Wayfarers” went smoothly, a fourth will follow this month and the annual evening of the Noverre Society, featuring young choreographers, is yet to come. “Wayfarers” is a triple bill consisting of two world premieres, Edward Clug’s “No Men’s Land” and Demis Volpi’s “Aftermath”, framing Maurice Béjart’s “Songs of a Wayfarer”, a work familiar to the Stuttgart audience.

Stuttgart Ballet’s innovative energy seems unstoppable. Some days ago this season’s third premiere, “Wayfarers” went smoothly, a fourth will follow this month and the annual evening of the Noverre Society, featuring young choreographers, is yet to come. “Wayfarers” is a triple bill consisting of two world premieres, Edward Clug’s “No Men’s Land” and Demis Volpi’s “Aftermath”, framing Maurice Béjart’s “Songs of a Wayfarer”, a work familiar to the Stuttgart audience.

Sparing neither trouble nor expense, both new creations had new music. Slovene Milko Lazar had been commissioned for the music of “No Men’s Land”. His suite of five movements for cello and full orchestra, belonging to the field of minimal and postmodern music, evokes an energetic, martial atmosphere. Only a cello solo by Zoltan Paulich provided a little lyricism amidst the unvaryingly pulsing rhythm.

Clug’s starting point were the particularities of the male sex. A question like ‘What have men accomplished since evolving upright walking?’ got the answer of ‘Killing each other!’. ‘What kind of power drives men crazy and prompts their incredible self-destruction?’ was addressed during the creative process in the studio. Twenty of Stuttgart Ballet’s male showpieces brought the choreographic result to life. Bare-chested and dressed in dark blue tracksuit pants and black, knee-high leg warmers (costumes by Thomas Mika), they became soldiers on the parade ground, lining up in file at the beginning. Playing war seemed the leitmotif in what followed. Must this ballet be taken seriously as a contribution to this year’s commemoration of World War I?

Ballet exercises turned into military ones as depersonalized men moved like machines and stood at attention. Friction, conflict and power games relating to pecking order and accompanied by mutual indignities such as pulling an opponents pants down in public, were key issues. Only Brent Parolin, ticking differently in his solo, tried to flee his comrades’ rigidity.

Ballet exercises turned into military ones as depersonalized men moved like machines and stood at attention. Friction, conflict and power games relating to pecking order and accompanied by mutual indignities such as pulling an opponents pants down in public, were key issues. Only Brent Parolin, ticking differently in his solo, tried to flee his comrades’ rigidity.

Later, the men embraced army coats from behind, coats which had hung in rows along the ceiling. They touched them admiringly. Concealed by the coats the dancers dangled like hanged men at one  point. Also employed were smoke mortars. Why, though, did one man crawl on all fours, his head covered by a bag, his hands wedged into pointe shoes? At least it looked frighteningly.

point. Also employed were smoke mortars. Why, though, did one man crawl on all fours, his head covered by a bag, his hands wedged into pointe shoes? At least it looked frighteningly.

When many dancers occupied the stage, at least there was an interesting dynamic. With only a few bodies, things became boring. Neither the smoke spitting igniter cords, which were repeatedly sparked, nor the strikingly lit clouds of smoke they left behind, made a lasting impression.

Clug’s finale was, on the one hand, provocative. On the other hand, it was a platitude that made one sigh resignedly. Ten men sat on the shoulders of their respective dance partners, whose upwardly stretched arms and clenched hands resembled erections. Respect was finally paid to the most virile, the one who sustained his position longest. What a crass concept of masculinity! Dear men, don’t you have more to offer?

“Aftermath” by Stuttgart Ballet’s young resident choreographer, Demis Volpi, was inspired by songs of Mercedes Sosa, a folk singer in Volpi’s home country of Argentina. Sosa sang about what happens when artists fall silent. ‘What would happen if artists stop fighting for their artistic freedom and when they then lose this freedom?’ was Volpi’s narrowly defined issue. To avoid any misunderstanding between the fight against the loss of art and the battle of the sexes, Volpi cast his ballet with women only. Twenty-five in all, the female counterpart of Clug’s all-male romp.

The score, composed by Michael Gordon, was brand new. It started with high-volume cacophony. I sat thunderstruck. Expertly led by conductor James Tuggle, the orchestra seethed and blustered.

The score, composed by Michael Gordon, was brand new. It started with high-volume cacophony. I sat thunderstruck. Expertly led by conductor James Tuggle, the orchestra seethed and blustered.

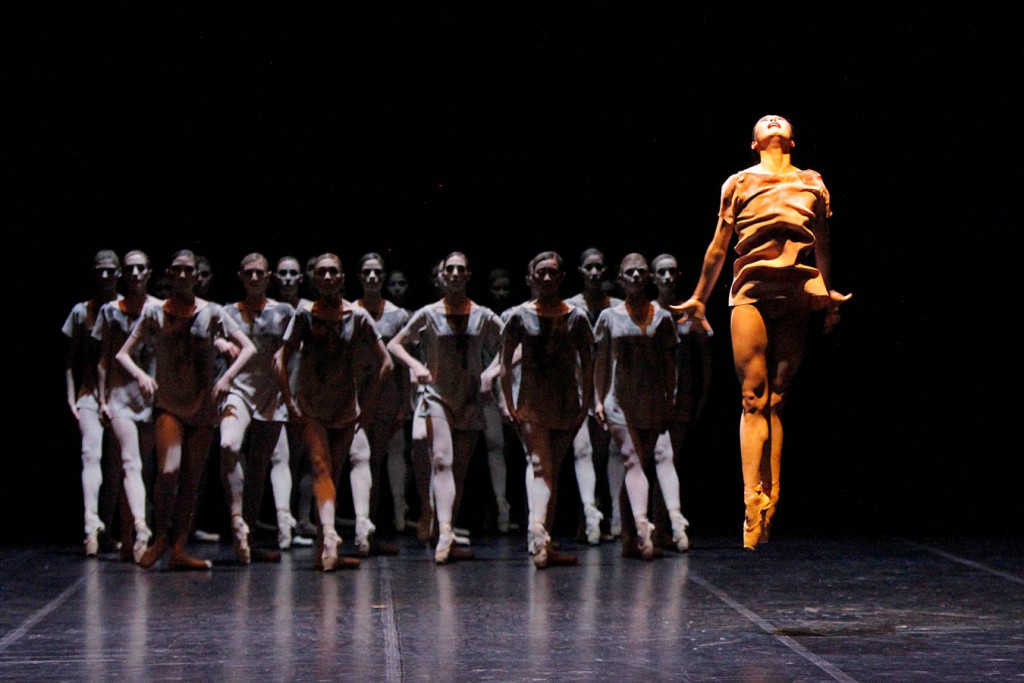

Hyo-Jung Kang portrayed the artist, struggling for existence. Her initial, long solo was intense and, although there was no visible danger, she seemed to be fighting hard. Maybe she was battling herself? The situation deteriorated when Kang was encircled by menacing masses: ugly creatures, uniformly clad in stained gray shirts. Kang wore a washed-out red one.  Faces were chalk white and eyes were black (costumes by Katharina Schlipf). Relentlessly in trouble, Kang was surrounded and enveloped over and over again by the gray crowd. Fascinating how the corps moved as a whole, how lines, clusters or narrowing and widening circles were formed! Using their legs like pointers, the sound of the grays’ pointe shoes – the ‘toktoktok’ – seemed to call artist Kang to order. Undulating head, neck and shoulders back and forth, the dancers looked like short-necked, voracious monsters. Clever lighting emphasized the weird impression. Several times Kang freed herself gasping for breath, but ultimately she was swallowed by the collective. The threatening patter of the pointe shoes increased in volume, becoming loud and resounding throughout the dark, final emptiness.

Faces were chalk white and eyes were black (costumes by Katharina Schlipf). Relentlessly in trouble, Kang was surrounded and enveloped over and over again by the gray crowd. Fascinating how the corps moved as a whole, how lines, clusters or narrowing and widening circles were formed! Using their legs like pointers, the sound of the grays’ pointe shoes – the ‘toktoktok’ – seemed to call artist Kang to order. Undulating head, neck and shoulders back and forth, the dancers looked like short-necked, voracious monsters. Clever lighting emphasized the weird impression. Several times Kang freed herself gasping for breath, but ultimately she was swallowed by the collective. The threatening patter of the pointe shoes increased in volume, becoming loud and resounding throughout the dark, final emptiness.

Volpi stretched his theme out for nearly twenty-five minutes – much too long. After ten minutes it was obvious that nothing new was in store for us. The artist fought to survive, but – this will sound heretical – why should the art Volpi depicted be preserved? Where was its beauty, its ability to disturb, stimulate and inspire? By not bringing the elementary importance of art to mind, Volpi failed to highlight how drastic the loss of art would be.

Compared to the fast-paced, edgy and sensationalistic novelties, the central piece, Béjart’s “Songs of a Wayfarer” proved to be a restorative contrast. Originally created in 1971 for Rudolf Nureyev and Paolo Bortoluzzi, it was also performed elsewhere. Marcia Haydée, Stuttgart Ballet’s artistic director from 1976-1996, managed to obtain it for Stuttgart’s Ricky (Richard Cragun) and Egon (Madsen) in 1976. It was a longstanding success in Stuttgart. For artistic director Reid Anderson, who had also danced as ‘Wayfarer’ back then, the piece’s revival after almost twenty years

Compared to the fast-paced, edgy and sensationalistic novelties, the central piece, Béjart’s “Songs of a Wayfarer” proved to be a restorative contrast. Originally created in 1971 for Rudolf Nureyev and Paolo Bortoluzzi, it was also performed elsewhere. Marcia Haydée, Stuttgart Ballet’s artistic director from 1976-1996, managed to obtain it for Stuttgart’s Ricky (Richard Cragun) and Egon (Madsen) in 1976. It was a longstanding success in Stuttgart. For artistic director Reid Anderson, who had also danced as ‘Wayfarer’ back then, the piece’s revival after almost twenty years  has been very important.

has been very important.

“Songs of a Wayfarer” was Gustav Mahler’s first song cycle, composed between 1884 and 1885. Its four movements are about a journeyman, who tries to get over an unhappy love affair. Does wandering from place to place console him? In Béjart’s interpretation, the young, lovesick journeyman is accompanied by another man. At first merely observant, he later shows his protegee the world. Representing omniscient fate, he seems to manipulate the one entrusted to him, but then also supports and consoles him. The mysterious companion was Evan McKie. He seemed to be pulling the strings of fate ever so remotely. Elegantly reserved, he leaves it to the journeyman – Jason Reilly – to be the center of attention. Reilly, back on stage after a long absence due to injury, plumbed the depths of his role, carefully and sensitively carving out its nuances. In fact he was the only one all evening long to radiate energy.

McKie and Reilly mastered the technical demands of their roles flawlessly. Baritone Peter Schöne’s intonation of Mahler’s songs was equally beautiful.

Wayfarers – who traditionally travel around to gain experience while honing their skills and learning from masters in their field – are yet-to-be masters. Béjart had arrived, while Clug and Volpi are still on the road.

| Links: | Stuttgart Ballet’s Homepage | ||

| Photos: | 1. | Edward Clug, Maurice Béjart and Demis Volpi, “Wayfarers”, Stuttgart Ballet 2014 | |

| 2. | Louis Stiens and Constantine Allen, “No Men’s Land” by Edward Clug, Stuttgart Ballet 2014 | ||

| 3. | Constantine Allen, Roman Novitzy, Brent Parolin and ensemble, “No Men’s Land” by Edward Clug, Stuttgart Ballet 2014 | ||

| 4. | Hyo-Jung Kang and ensemble, “Aftermath” by Demis Volpi, Stuttgart Ballet 2014 | ||

| 5. | Hyo-Jung Kang and ensemble, “Aftermath” by Demis Volpi, Stuttgart Ballet 2014 | ||

| 6. | Jason Reilly and Evan McKie, “Songs of a Wayfarer” by Maurice Béjart, Stuttgart Ballet 2014 | ||

| 7. | Jason Reilly and Evan McKie, “Songs of a Wayfarer” by Maurice Béjart, Stuttgart Ballet 2014 | ||

| 8. | Evan McKie and Jason Reilly, “Songs of a Wayfarer” by Maurice Béjart, Stuttgart Ballet 2014 | ||

| all photos © Stuttgart Ballet 2014 | |||

| Editing: | Laurence Smelser, George Jackson |