“The Girl and the Knife Thrower”, “Le Sacre du Printemps”

Bavarian State Ballet

Reithalle (Riding Hall)

Munich, Germany

June 19, 2014

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2014 by Ilona Landgraf

One of this season’s revivals that dance connoisseurs in Germany awaited with much interest, was Mary Wigman’s “Le Sacre du Printemps”. More than fifty years after its Berlin premiere, the Bavarian State Ballet tried to bring the piece back to the stage together with a modern counterpart: Simone Sandroni’s “The Girl and the Knife Thrower”.

One of this season’s revivals that dance connoisseurs in Germany awaited with much interest, was Mary Wigman’s “Le Sacre du Printemps”. More than fifty years after its Berlin premiere, the Bavarian State Ballet tried to bring the piece back to the stage together with a modern counterpart: Simone Sandroni’s “The Girl and the Knife Thrower”.

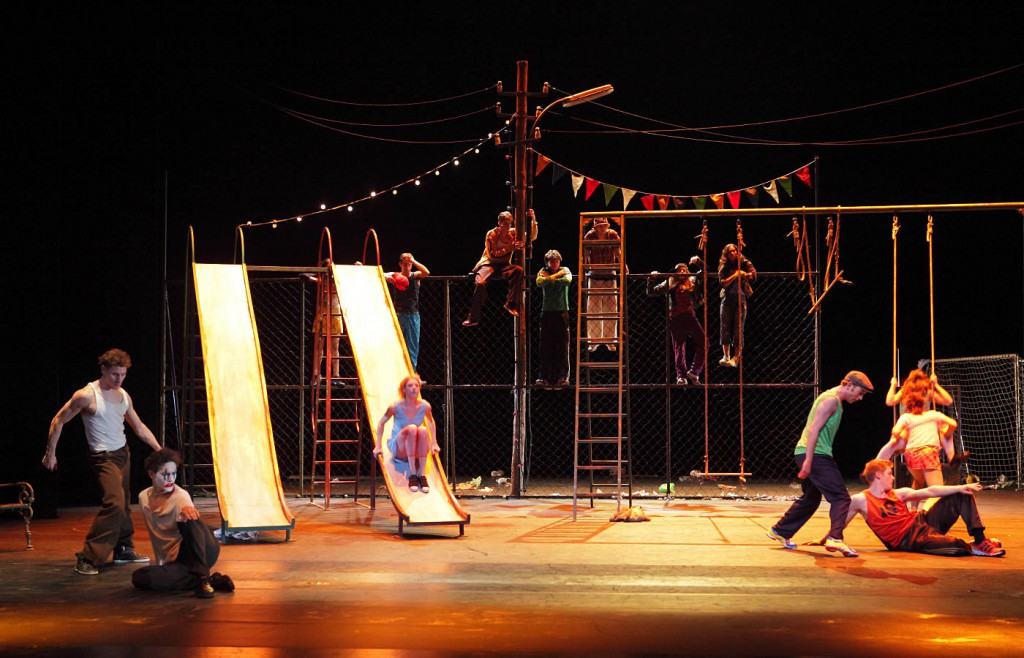

Sandroni’s ballet is based on an eponymous cycle of poems by German writer Wolf Wondratschek about singular moments in the daily life of a circus troupe. The main characters are the knife thrower, his target – a girl, two other young women and a clown. Sandroni relocated the goings-on to a filthy playground and supplemented the group of itinerants by devising roles for two hip-hop Russians.

The gang hung out, seesawed, slid, hopped around a sand box, sat on the park benches and drank alcohol. From time to time they would dance – as a pastime or to relieve boredom or to vent tensions and aggressions. They also rioted, wielding iron bars. Recorded music by the group 48nord, a mix of neo-rock and new sound, started and stopped whenever the protagonists wanted it to. The two young women (Giuliana Bottino, Francesca dell’Aria) bickered with predictable regularity; the clown (Matej Urban) tried on faces variously made

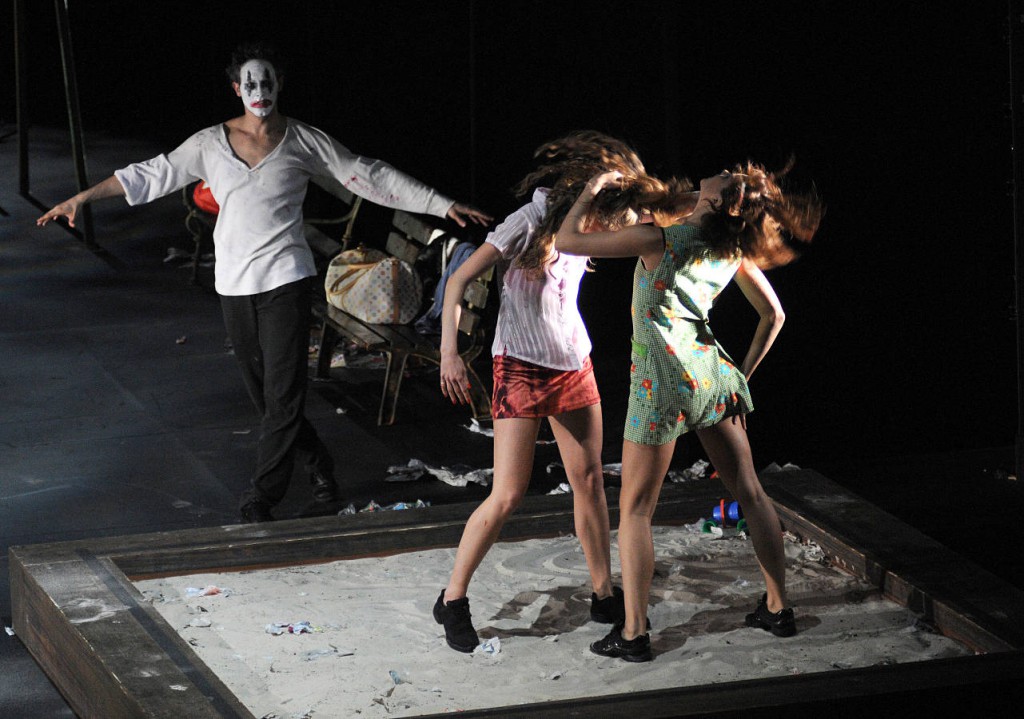

The gang hung out, seesawed, slid, hopped around a sand box, sat on the park benches and drank alcohol. From time to time they would dance – as a pastime or to relieve boredom or to vent tensions and aggressions. They also rioted, wielding iron bars. Recorded music by the group 48nord, a mix of neo-rock and new sound, started and stopped whenever the protagonists wanted it to. The two young women (Giuliana Bottino, Francesca dell’Aria) bickered with predictable regularity; the clown (Matej Urban) tried on faces variously made  up, but the only refreshing dance number came from the hip-hop Russians (Ilia Sarkisov, Dustin Klein). Wearing sneakers, they made fun of a classical pas de deux. The principal girl (Emma Barrowman) danced with self-assurance while pretending to be a dreamy little innocent. Yet the way in which she lay on the floor or in the sand box, writhing, with her red underpants peeping out from under an ultra-short dress, told quite another story. Knives weren’t thrown. Instead the knife thrower (Nikita Korotkov), who was the group’s melancholy boss, contented himself with standing next to Barrowman lying down, merely looking at her or stepping provocatively between her spread legs.

up, but the only refreshing dance number came from the hip-hop Russians (Ilia Sarkisov, Dustin Klein). Wearing sneakers, they made fun of a classical pas de deux. The principal girl (Emma Barrowman) danced with self-assurance while pretending to be a dreamy little innocent. Yet the way in which she lay on the floor or in the sand box, writhing, with her red underpants peeping out from under an ultra-short dress, told quite another story. Knives weren’t thrown. Instead the knife thrower (Nikita Korotkov), who was the group’s melancholy boss, contented himself with standing next to Barrowman lying down, merely looking at her or stepping provocatively between her spread legs.

I remember a dress rehearsal of “The Girl and the Knife Thrower” in Munich’s Residenztheater which I attended with the German dance critic Horst Koegler shortly before his death in 2012. Staunchly resting upon his walking stick, he glanced at me and, with ironic resignation, wondered whether the ballet was already over. Since then, the piece has been reworked and slightly shortened. It certainly benefited from the different venue: The Reithalle is less spacious than the Residenztheater and the audience is closer to the stage. Still, it seems mostly banal. What a waste of talented dancers and forty minutes!

Many in the audience had come to the Reithalle primarily for the double bill’s second piece: “Le Sacre du Printemps” by Mary Wigman (1886 – 1973). In January 1957, Wigman – the icon of New German Dance – had been commissioned by Berlin’s Federal State Government to make a new “Sacre”. The premiere was to take place at the Berlin Festival in September of that year. Though the art represented by Wigman was still appreciated back then, her approach was considered outdated. Her intention was to transform and express emotional and mental conditions – inner sensations – as visible movement. For Wigman,

Many in the audience had come to the Reithalle primarily for the double bill’s second piece: “Le Sacre du Printemps” by Mary Wigman (1886 – 1973). In January 1957, Wigman – the icon of New German Dance – had been commissioned by Berlin’s Federal State Government to make a new “Sacre”. The premiere was to take place at the Berlin Festival in September of that year. Though the art represented by Wigman was still appreciated back then, her approach was considered outdated. Her intention was to transform and express emotional and mental conditions – inner sensations – as visible movement. For Wigman,  “Sacre” was a work of existential necessity, something she had to do. But in Germany, the public and the press preferred classical ballet. The Festival’s dance evening was supposed to link German tradition and, because of Stravinsky’s music, European tradition to the then (1957) current avant-garde – as exemplified by the world premiere of “Maratona di Danza” by Italian film director Luchino Visconti, composer Hans-Werner Henze and choreographer Dirk Sanders. Jean Babilée danced the leading character. Also in the cast was Konstanze Vernon, who would become major in Munich’s ballet scene.

“Sacre” was a work of existential necessity, something she had to do. But in Germany, the public and the press preferred classical ballet. The Festival’s dance evening was supposed to link German tradition and, because of Stravinsky’s music, European tradition to the then (1957) current avant-garde – as exemplified by the world premiere of “Maratona di Danza” by Italian film director Luchino Visconti, composer Hans-Werner Henze and choreographer Dirk Sanders. Jean Babilée danced the leading character. Also in the cast was Konstanze Vernon, who would become major in Munich’s ballet scene.

“Sacre” was Wigman’s last realization of her ideas about what could be achieved on stage. The role of the sacrificial girl was taken by German modern dancer Dore Hoyer (1911-1967), herself an expressionist choreographer. Hoyer not only choreographed her own solo in “Sacre” but other sections such as the men’s competition. Being ‘The Chosen One’ seemed a mirror of Hoyer’s attitude towards life. In many respects she felt herself to be a victim, a victim of the National Socialists, or, later of the occupying forces’ cultural policy. Generally she expressed her feeling of grief in dance, which didn’t win her an audience. “Sacre”, however, was a triumph in 1957.

Repeatedly obsessed by thoughts of death, Hoyer committed suicide by poisoning herself in 1967.

Wigman’s “Sacre”, after the series of performances that followed the premiere, never returned to the stage until now. Its current revival was initiated and funded by the German ‘Dance Fund Legacy’ (‘Tanzfonds Erbe’), an initiative of the Federal Cultural Foundation to bring Germany’s lost dance legacy back to life. Three ensembles cooperated on the project: the Dance Theater of Bielefeld, the Theater Osnabrück’s company and the Bavarian State Ballet. The first premiere took place in Osnabrück in November 2013, some days later ‘”Sacre” was performed in Bielefeld. In either case the cast had been reduced from the original 45 to 29 dancers. Bavarian State Ballet took over the production this month with a full sized cast but, compared to Osnabrück and Bielefeld, the occasion was musically limited. Stravinsky’s score was the two piano version rather than the orchestral one because the Riding Hall has no orchestra pit.

Wigman’s “Sacre”, after the series of performances that followed the premiere, never returned to the stage until now. Its current revival was initiated and funded by the German ‘Dance Fund Legacy’ (‘Tanzfonds Erbe’), an initiative of the Federal Cultural Foundation to bring Germany’s lost dance legacy back to life. Three ensembles cooperated on the project: the Dance Theater of Bielefeld, the Theater Osnabrück’s company and the Bavarian State Ballet. The first premiere took place in Osnabrück in November 2013, some days later ‘”Sacre” was performed in Bielefeld. In either case the cast had been reduced from the original 45 to 29 dancers. Bavarian State Ballet took over the production this month with a full sized cast but, compared to Osnabrück and Bielefeld, the occasion was musically limited. Stravinsky’s score was the two piano version rather than the orchestral one because the Riding Hall has no orchestra pit.

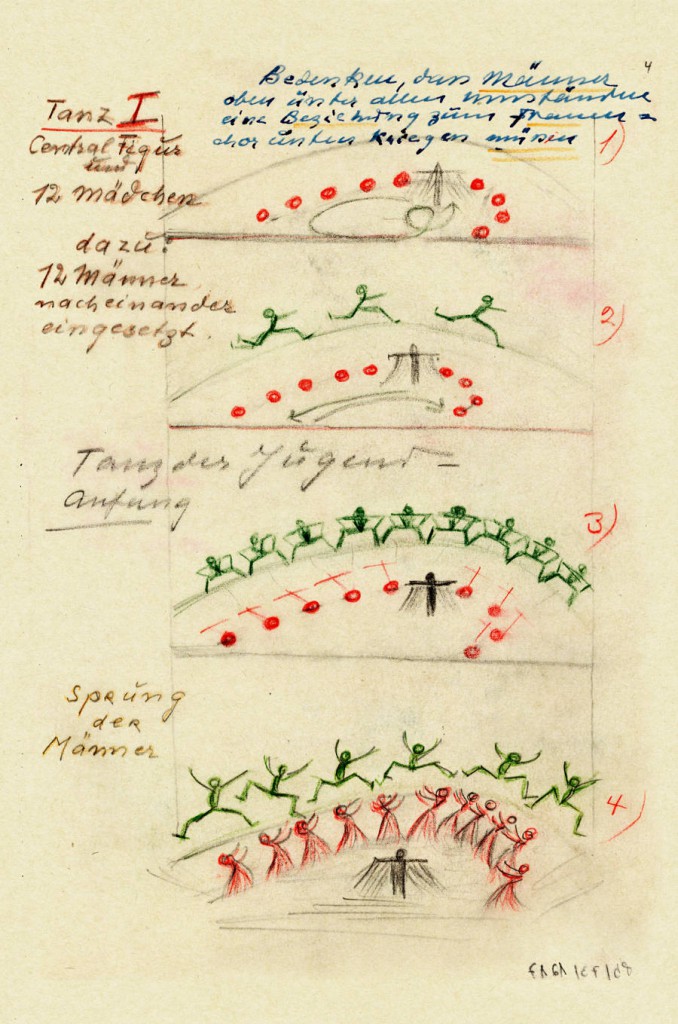

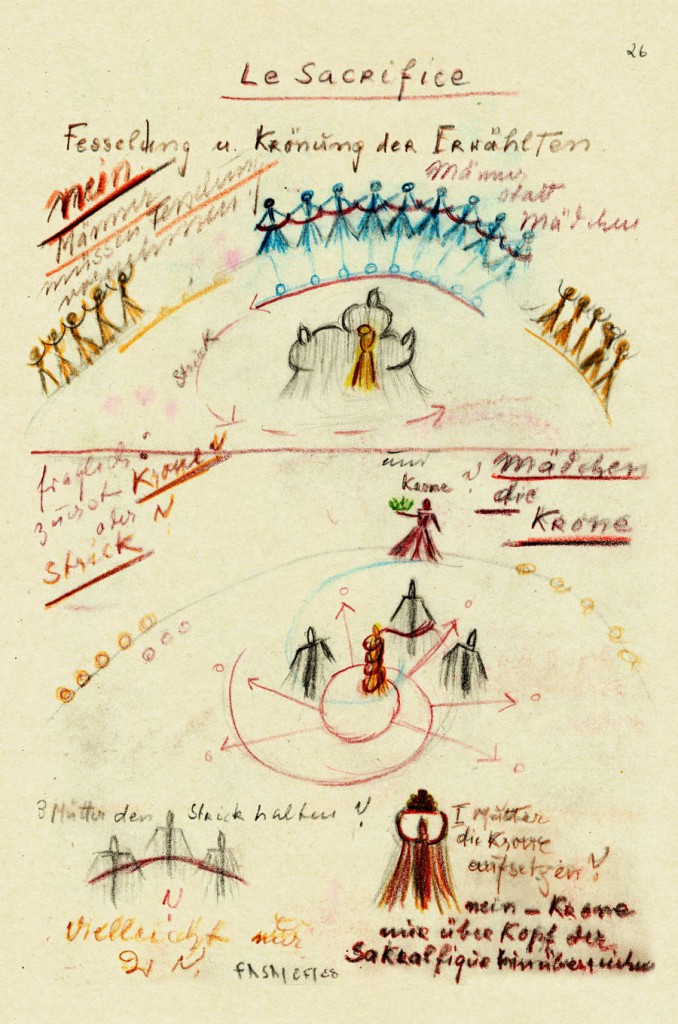

Though there’s plenty of archival material on “Sacre” in Berlin’s Academy of the Arts and in the German Dance Archive in Cologne – notes and sketches by Wigman as well as the estate of Dore Hoyer – there are actually no certain facts. The extant information can be interpreted in different ways. Choreographic gaps had to be filled in, mainly relating to the role of ‘The Chosen One’ and to the men’s competition i.e., the sections made by Hoyer. Hence an actual reconstruction was impossible. The attempt was rather to come as close as possible to Wigman’s intentions. In charge of this task was a team: The German choreographer Henrietta Horn, assisted by Susan Barnett and Wigman’s former student Katherina Sehnert. Emma Lewis Thomas and Brigitta Herrmann from the USA, who had both studied with Wigman, and Susanne Linke supported the team as advisors. Alfred Peter reconstructed the set and the costumes according to drawings, black and white photos and Wilhelm Reinking’s original figurines of the costumes.

Though there’s plenty of archival material on “Sacre” in Berlin’s Academy of the Arts and in the German Dance Archive in Cologne – notes and sketches by Wigman as well as the estate of Dore Hoyer – there are actually no certain facts. The extant information can be interpreted in different ways. Choreographic gaps had to be filled in, mainly relating to the role of ‘The Chosen One’ and to the men’s competition i.e., the sections made by Hoyer. Hence an actual reconstruction was impossible. The attempt was rather to come as close as possible to Wigman’s intentions. In charge of this task was a team: The German choreographer Henrietta Horn, assisted by Susan Barnett and Wigman’s former student Katherina Sehnert. Emma Lewis Thomas and Brigitta Herrmann from the USA, who had both studied with Wigman, and Susanne Linke supported the team as advisors. Alfred Peter reconstructed the set and the costumes according to drawings, black and white photos and Wilhelm Reinking’s original figurines of the costumes.

The sacrificial dance took place on an elliptic, slightly tilted platform nearly filling the entire stage. Next to ‘The Chosen One” (Ilana Werner) and ‘The Wise Man” (Cyril Pierre), a motherly character (Séverine Ferrolier) and two Priestesses (Lisa-Maree  Cullum, Freya Thomas) constituted the ritual’s inner circle. More peripheral were a choir of men and women, a group of bald-headed elders, a lad (Javier Amo), a girl with a crown (Ivy Amista), the leader of the men’s dance (Tigran Mikayelyan) and a frolicking couple of lovers (Mai Kono, Zoltan Mano Beke). The colors of the costumes, however, differentiated only among three groups: the motherly character, the priestesses, the wise men and the four elders wore dove blue, floor-length robes. All other women’s dresses were plain, ankle-length and in different shades of warm yellow. The men wore short brown pants and sleeveless shirts. Apart from the groups, a simple, raspberry-red, floor-length dress made The Chosen One stand out.

Cullum, Freya Thomas) constituted the ritual’s inner circle. More peripheral were a choir of men and women, a group of bald-headed elders, a lad (Javier Amo), a girl with a crown (Ivy Amista), the leader of the men’s dance (Tigran Mikayelyan) and a frolicking couple of lovers (Mai Kono, Zoltan Mano Beke). The colors of the costumes, however, differentiated only among three groups: the motherly character, the priestesses, the wise men and the four elders wore dove blue, floor-length robes. All other women’s dresses were plain, ankle-length and in different shades of warm yellow. The men wore short brown pants and sleeveless shirts. Apart from the groups, a simple, raspberry-red, floor-length dress made The Chosen One stand out.

Compared to Nijinsky’s, Neumeier’s or Tetley’s versions, the Wigman sacrificial person knows her destiny and accepts her fate. Like a mystically enraptured being she repeatedly stares into the auspicious distance or folds her arms in front of her chest as if holding something inconceivably divine in her hands. Being rebellious isn’t at all in her nature. Rather she is a redeemer figure. That a thick rope was wrapped around her and that she was crowned with a wreath of braided small twigs during the course of her devotional ritual was reminiscent of the Christian Lady of Sorrows. After unwinding the rope, she danced her final solo – looking as if she had been transported into another mystical state of consciousness. At last she collapsed.

The rite was a formal ceremony interspersed with playful moments – like the men feigning to fight. It was a religious ceremony comparable to those at the Vatican, The corps’ movement pattern kept changing fluently. Dancers formed circles and aisles or clusters that had intriguingly clear structures and strict synchronicity. Though being bare footed, there was no frenzy, no stomping, no force. Instead, Wigman celebrated mysticism. Making a sacrifice, or sacrificing oneself should be a path to – or a sign of – religious transcendence. In fact, though, the whole thing was pretentious – a bloodless and powerless ritual. In her notes Wigman wrote about ‘The Chosen One’ being chased in ecstatic frenzy. But there was not a bit of a frenzy and the ecstasy merely an artificial one. Maybe in the 1950s the Wigman “Sacre” radiated genuine inner strength. Today, the New German Dance seems definitely antiquated.

The rite was a formal ceremony interspersed with playful moments – like the men feigning to fight. It was a religious ceremony comparable to those at the Vatican, The corps’ movement pattern kept changing fluently. Dancers formed circles and aisles or clusters that had intriguingly clear structures and strict synchronicity. Though being bare footed, there was no frenzy, no stomping, no force. Instead, Wigman celebrated mysticism. Making a sacrifice, or sacrificing oneself should be a path to – or a sign of – religious transcendence. In fact, though, the whole thing was pretentious – a bloodless and powerless ritual. In her notes Wigman wrote about ‘The Chosen One’ being chased in ecstatic frenzy. But there was not a bit of a frenzy and the ecstasy merely an artificial one. Maybe in the 1950s the Wigman “Sacre” radiated genuine inner strength. Today, the New German Dance seems definitely antiquated.

Nonetheless, it is only by trying to make an important choreographer’s work available to a contemporary audience that our understanding of dance history becomes possible. Thus, a ‘Thank you’ to the reconstruction team for adding another piece to the jigsaw of tradition!

“Le Sacre du Printemps” will remain in Bavarian State’s repertory for next season, when it will have full orchestral accompaniment. A second piece, steeped in history, Gerhard Bohner’s “The Triadic Ballet”, will complete the bill.

| Links: | Bavarian State Ballet’s Homepage | |

| Photos: | (Some photos show a different cast of an earlier performance.) | |

| “The Girl and the Knife Thrower” | ||

| 1. | Ensemble, “The Girl and the Knife Thrower” by Simone Sandroni, Bavarian State Ballet © Wilfried Hösl 2014 | |

| 2. | Giuliana Bottino (Woman), Emma Barrowman (The Girl), Matej Urban (Clown), Isabelle Sévers (Woman) and Wlademir Faccioni (The Knife Thrower), “The Girl and the Knife Thrower” by Simone Sandroni, Bavarian State Ballet © Wilfried Hösl 2014 | |

| 3. | Matej Urban (Clown), Giuliana Bottino (Woman), and Francesca dell’Aria (Woman), “The Girl and the Knife Thrower” by Simone Sandroni, Bavarian State Ballet © Wilfried Hösl 2014 | |

| 4. | Nikita Korotkov (The Knife Thrower) and Emma Barrowman (The Girl), “The Girl and the Knife Thrower” by Simone Sandroni, Bavarian State Ballet © Wilfried Hösl 2014 | |

| 5. | Emma Barrowman (The Girl), “The Girl and the Knife Thrower” by Simone Sandroni, Bavarian State Ballet © Wilfried Hösl 2014 | |

| “Le Sacre du Printemps” | ||

| 6. | Norbert Graf (The Wise Man) and ensemble, “Le Sacre du Printemps” by Mary Wigman, Bavarian State Ballet © Wilfried Hösl 2014 | |

| 7. | Tigran Mikayelyan (Leader of the Men’s Dance) and Lukáš Slavický, “Le Sacre du Printemps” by Mary Wigman, Bavarian State Ballet © Wilfried Hösl 2014 | |

| 8. | Norbert Graf (The Wise Man), Daria Sukhorukova (Motherly Figure), Lisa-Maree Cullum (Priestess), Freya Thoms (Priestess), and ensemble, “Le Sacre du Printemps” by Mary Wigman, Bavarian State Ballet © Wilfried Hösl 2014 | |

| 9. | Ensemble, “Le Sacre du Printemps” by Mary Wigman, Bavarian State Ballet © Wilfried Hösl 2014 | |

| 10. | Ilana Werner (The Chosen One), “Le Sacre du Printemps” by Mary Wigman, Bavarian State Ballet © Wilfried Hösl 2014 | |

| 11. | Ilana Werner (The Chosen One), “Le Sacre du Printemps” by Mary Wigman, Bavarian State Ballet © Wilfried Hösl 2014 | |

| 12. | Sketches for “Le Sacre du Printemps” by Mary Wigman, 1957, Mary-Wigman-Archive of the Academy of the Arts, Berlin © Mary Wigman Foundation of the German Dance Archive Cologne | |

| 13. | Sketches for “Le Sacre du Printemps” by Mary Wigman, 1957, Mary-Wigman-Archive of the Academy of the Arts, Berlin © Mary Wigman Foundation of the German Dance Archive Cologne | |

| Editing: | George Jackson, Laurence Smelser |