by Horst Koegler

Transcribed from a lecture given in 1976 at the Noverre Society in Stuttgart.

Stuttgart, Germany

June 29, 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Ilona Landgraf

Had anyone asked John Cranko what ballet dramaturgy is, I imagine he might have answered, “Ballet dramaturgy is the figment of a frustrated German ballet critic’s imagination, and that person is Horst Koegler.” I have no illusions whatsoever about my persistent demand for more ballet dramaturgy. I dwell on it in order to correct an intolerable situation that puts ballet at a disadvantage compared to drama and opera.

Had anyone asked John Cranko what ballet dramaturgy is, I imagine he might have answered, “Ballet dramaturgy is the figment of a frustrated German ballet critic’s imagination, and that person is Horst Koegler.” I have no illusions whatsoever about my persistent demand for more ballet dramaturgy. I dwell on it in order to correct an intolerable situation that puts ballet at a disadvantage compared to drama and opera.

Because the term ballet dramaturgy didn’t exist in the past and ballet got along without it, some people today do not see the need for it. Although I can understand this attitude histori- cally, I don’t agree. Theater dramaturgy has existed ever since Aristotle’s Poetics, which spelled out the rules for comedy and tragedy. We also know what Gotthold Lessing’s Hamburg Dramaturgy accomplished for the German theater. Opera dramaturgy is less explicitly fixed and, despite the Florentine Camerata’s erudite debates on the topic, never produced globally accepted standards.

Still, evidence for the existence of both opera dramaturgy and theater dramaturgy can be found on our stages, even if here in Stuttgart it’s doubtful. But whoever heard of ballet dramaturgy in our theaters until now? The profession of ballet dramaturge doesn’t even exist. Where ballet dramaturgy is actually practiced in our country (and I don’t exclude Stuttgart by any means), it is either in the safekeeping of the ballet director himself (as with John Neumeier in Hamburg) or is an adjunct of opera dramaturgy.

What amazes me more is that our contemporary dance theater companies, whose directors (such as Jochen Ulrich in Cologne and formerly Gerhard Bohner in Darmstadt) are quite aware that ballet (or dance) dramaturgy is needed, do not advocate for the establishment of a dramaturge position in their own companies. Pina Bausch in Wuppertal, too, showed no such initiative. Then, Edmund Gleede [director of the Bavarian State Ballet] fell into her lap. I don’t even know if she’s especially happy about that, although the recent Stravinsky ballet evening in Wuppertal is the only one in the three years there of Bausch’s creative work that, owing to Gleede’s participation, has a total dramaturgic concept.

“Where to begin with what doesn’t exist at all?” I hear the balletgoer ask. This is a difficulty I don’t underestimate. But without effective encouragement by theater people, hardly anyone will tackle this laborious task, this pioneering achievement. I’m convinced that there are young students at our universities who would be interested in such a job and would be qualified for it if they were encouraged.

“Where to begin with what doesn’t exist at all?” I hear the balletgoer ask. This is a difficulty I don’t underestimate. But without effective encouragement by theater people, hardly anyone will tackle this laborious task, this pioneering achievement. I’m convinced that there are young students at our universities who would be interested in such a job and would be qualified for it if they were encouraged.

I know at least one woman at the University of Munich who would be an ideal ballet dramaturge, if only she were given the chance. However, even in Hamburg, where the opera luxuriates with four established dramaturgy posts, Neumeier seems reluctant to offer her a regular position. For the duration she is employed piecemeal, while Neumeier himself, who is apprehensive of “dramaturgy,” refers to her as a researcher, an investigator, someone who supports him in exploring sources for his next production. She explored so thoroughly, found so much new material and new insights, that Neumeier’s upcoming Swan Lake promises to be significant and a sensation. On the other hand, Stuttgart thought of purchasing from the Kirov the existing antiquated 1952 production of The Sleeping Beauty by Konstantin Sergeyev, rather than mounting its own.

What I wonder about again and again is why no dramaturges emerge from the ranks of the dancers themselves. Often the transition to another profession is really problematic for them. During their careers as dancers, the most intelligent must have realized how much today’s ballets all suffer from a lack of dramaturgy. I think that especially dancers, with their knowledge of the medium, are qualified to be ideal ballet dramaturges, provided they pick up the necessary knowledge. Slumbering here is the chance for a successful profession – unrecognized up to now.

I am advocating for ballet dramaturges not from ulterior motives. I do not intend to become one myself, and certainly not at the Stuttgart Ballet. Just as I’d never want to become a ballet company director anywhere. I did my apprenticeship in the theater before embarking on writing and haven’t the least ambition to reenter by the stage door as a dramaturge or stage director at the opera (which I already was), nor as ballet director or general manager.

I am advocating for ballet dramaturges not from ulterior motives. I do not intend to become one myself, and certainly not at the Stuttgart Ballet. Just as I’d never want to become a ballet company director anywhere. I did my apprenticeship in the theater before embarking on writing and haven’t the least ambition to reenter by the stage door as a dramaturge or stage director at the opera (which I already was), nor as ballet director or general manager.

Even if crossing from theater to journalism has become more and more frequent recently, that’s not my striving. I consider myself a ballet journalist in the broadest sense of the word. I simply love to write, as difficult and increasingly hard as it is to exist as a freelance ballet journalist these days. Should I be frustrated? This might be the case, only I haven’t realized it myself up to now. Maybe I’m slow on the uptake.

Back to ballet dramaturgy. What should it be and what should it achieve? We have to distinguish between two different kinds of dramaturgy. One deals with the process of creating a performance; the other defines the profile of the repertory, maybe even of the company. Anyone who saw The Prince of Homburg at the Berliner Schaubühne at the Hallesches Tor experienced the ideal situation in which both kinds of dramaturgy were manifested. A completely new perception of a familiar classical play was the result of the interaction of dramaturgy and production. This dramaturgically initiated new perception became the hallmark of the repertory and the intention of the theater.

A stylistic phenomenon of similar coherence I find only in one ballet ensemble, New York City Ballet. Yet there is just as little deliberately practiced dramaturgy there as at The Royal Ballet or the Ballet of the 20th Century. The example of Berlin’s Schaubühne shows that dramaturgy doesn’t exist in isolation. It depends on what is being prepared for staging and on the production, by which the piece (whether drama, opera, ballet, and everything in between) is made alive in the theater. I overvalue the capabilities of dramaturgy not in the slightest. A production without dramaturgy is possible, and happens at most of our theaters. Whereas dramaturgy without production remains merely theory and is condemned to sterility.

Referring to ballet, is dramaturgy only another expression for drafting a libretto or scenario? Whoever believes this is profoundly wrong! A ballet dramaturge is not a librettist. De facto, it might seem to be the case. John Cranko was his own ballet dramaturge, even if he pretended not to know it. He considered a “dramaturge” to be a typically German invention. But there is no doubt that his big story ballets have their own dramaturgy. Contained in his Onegin, The Taming of the Shrew, and Carmen, and also his stagings of classics like Swan Lake and Nutcracker, there are entirely deliberate, highly intellectual considerations that preceded the creative process of choreographing. He might have phrased it differently, even rejected the term dramaturgy as too highbrow and preferred to talk of producing a libretto or a scenario.

Referring to ballet, is dramaturgy only another expression for drafting a libretto or scenario? Whoever believes this is profoundly wrong! A ballet dramaturge is not a librettist. De facto, it might seem to be the case. John Cranko was his own ballet dramaturge, even if he pretended not to know it. He considered a “dramaturge” to be a typically German invention. But there is no doubt that his big story ballets have their own dramaturgy. Contained in his Onegin, The Taming of the Shrew, and Carmen, and also his stagings of classics like Swan Lake and Nutcracker, there are entirely deliberate, highly intellectual considerations that preceded the creative process of choreographing. He might have phrased it differently, even rejected the term dramaturgy as too highbrow and preferred to talk of producing a libretto or a scenario.

So, Cranko was dramaturge, librettist, choreographer, and stage director, an impossible burden that is still commonly practiced in ballet. It certainly could also be blamed for the rapid wearing out of our choreographers’ core power for making ballets, simply because they are physically overchallenged. Today, nobody would expect an opera composer to write the libretto, compose the music, rehearse the parts with the singers and the orchestral musicians, and also mount and conduct the opera. Yet all this is expected quite naturally of today’s choreographers, whether the great Balanchine or the little Miss X in the middle of nowhere.

This example shows that choreography is the creative achievement of an author, an achievement comparable only to the job of a dramaturge or a composer, not a postcreative role done by a stage director or conductor. Indeed, choreographers are partly to blame for the crazy demands on their vigor.

One of the main reasons for this is that ballet still hasn’t developed a generally accepted notation system, one that allows choreographers to compose their ballets at their desks at home in order to hand over the choreographic score to the ballet’s stage directors for production afterwards. I know this is an idea considered by many dancers and choreographers as somehow absurd, but I think of today’s way of creating choreography on the living body of a dancer as an entirely anachronistic and above all uneconomical working process. It is simply outdated in this century.

However, there’s another reason for this no longer justifiable overstrain of our choreographers: their refusal to delegate co-creative responsibility. In this respect the choreographers of the past actually were one step ahead. In the past century, but partly still in Diaghilev’s time, they commissioned others to write their librettos. Neither La Sylphide, Giselle, Swan Lake, nor Sleeping Beauty has a libretto by the ballet’s initial choreographer.

However, there’s another reason for this no longer justifiable overstrain of our choreographers: their refusal to delegate co-creative responsibility. In this respect the choreographers of the past actually were one step ahead. In the past century, but partly still in Diaghilev’s time, they commissioned others to write their librettos. Neither La Sylphide, Giselle, Swan Lake, nor Sleeping Beauty has a libretto by the ballet’s initial choreographer.

Yet in these days our choreographers without exception feel obliged to write all their librettos themselves. It happens with Cranko as with Tetley, Béjart, MacMillan, Neumeier, and Grigorovich. Where the whole world nowadays aims to delegate responsibility, our choreographers cannot get enough of it, especially since in most cases they are also ballet directors, particularly of our largest troupes.

They all behave a little bit like Wagner, but he was wise enough to restrain his appetite for power to a few festival weeks in Bayreuth and he did leave the conducting to his staff there, while today our choreographers try to practice the Wagnerian plenitude of power for twelve months a year. No wonder constraints in the daily course of business often obstruct their view of crucial contemporary truths, for what’s happening in related artistic fields, for new perspectives and new approaches.

Raised in the world of ballet and shaped by its training method’s discipline, their minds work in well-trodden paths. It has always been done this way, has proved itself, and so it has to be like this. They don’t have the power any more to search for new approaches. In most cases they lack orientation about what’s going on next to them and are unable to use it as stimulation for their own work.

My concern is less a theoretical investigation of the term ballet dramaturgy than a highlighting of concrete examples from today’s ballet world, examples of work for which a dramaturge should be a necessity. I consider it a role for someone who provides ideas and is a supervisory authority for the choreographer, a first discussion partner.

My concern is less a theoretical investigation of the term ballet dramaturgy than a highlighting of concrete examples from today’s ballet world, examples of work for which a dramaturge should be a necessity. I consider it a role for someone who provides ideas and is a supervisory authority for the choreographer, a first discussion partner.

The role should include being the facilitator for a piece, determining what should be developed from scratch, and someone who moderates the dis- cussions among choreographer, librettist, composer, and stage and costume designer. The ideal ballet dramaturge should be equipped with a profound general knowledge in the humanities, be completely familiar with ballet history and informed up-to-the-minute about what’s going on in every artistic area. He or she should have a flair for artistic developmental processes and above all a skill that is a sine qua non: a great deal of imagination. A must is to articulate and reason, not just opinionate.

Still other traits are tactical diplomacy and being reasonable, but not dogmatic, since the dramaturge’s closest working partner is the choreographer. And choreographers, at least the really creative choreographers, are mostly extraordinarily sensitive and vulnerable people. So the dramaturge ought to know how to deal with people, especially those who call themselves “artists.” This ideal ballet dramaturge did exist, even if he himself had no idea that he was one and considered himself an impresario: Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev, the creator of the Ballets Russes, the company that from 1909 to 1929 set the course for modern ballet.

The dramaturge is a producer of ideas, a sedulous stimulus who, with his knowledge of the contemporary art scene, constantly places new suggestions into the choreographer’s hands. Even more than is the case in drama and opera, ballet people take existing pieces, the so-called classics as well as pieces of the modern repertory, as an immutable source for the libretto and the score, with the originality of the production arising mostly from the decor.

The dramaturge is a producer of ideas, a sedulous stimulus who, with his knowledge of the contemporary art scene, constantly places new suggestions into the choreographer’s hands. Even more than is the case in drama and opera, ballet people take existing pieces, the so-called classics as well as pieces of the modern repertory, as an immutable source for the libretto and the score, with the originality of the production arising mostly from the decor.

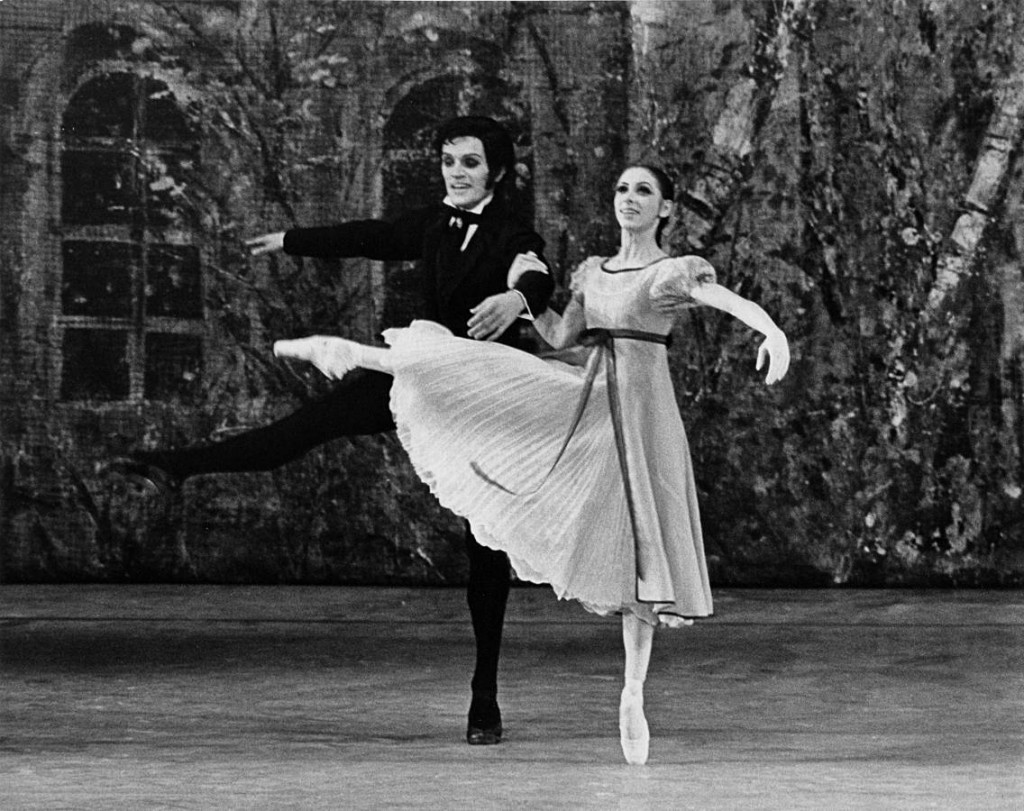

Cranko seemed perfectly aware of the need to see especially the classics from a new perspective. His Swan Lake productions in Stuttgart and Munich allow us to draw this conclusion, but most of all his Nutcracker in Stuttgart, which his new dramaturgy liberated from the captivity of being a Christmas ballet and made into a ballet for all seasons. However, Cranko would have staged this production with much more care and consistency and avoided the mishap with the decor had there been constant supervision by a dramaturge, for example, one like Diaghilev.

Neumeier pursued Cranko’s approach for his Nutcracker: he also converted it into a ballet fairy tale for all seasons but went one step farther by expanding it into an allegory on the art of ballet. His Drosselmeier is none other than the great Petipa himself, author of the original libretto. By all accounts from Hamburg we will experience something similar in Swan Lake, originating from Cranko but surpassing Cranko, namely the connection to Ludwig II of Bavaria.

Actually this reference existed already in the Munich production. It was not yet more distinct than in Stuttgart, being only a stage set and a reference in the decor, both by Jürgen Rose. That Neumeier seems to be identifying Prince Siegfried with Tchaikovsky and Ludwig II (according to Hans Mayer’s new book Außenseiter [Outsider]) is of eminent current interest.

That’s the current status of ballet’s classical dramaturgy. Eight years earlier Cranko took up his work in Stuttgart. Today people in Stuttgart talk a lot about preserving the Cranko heritage and about fortifying the foundation Cranko created. Obviously however, he was much more advanced in his under- standing of the classics than those responsible for ballet in Stuttgart today.

That’s the current status of ballet’s classical dramaturgy. Eight years earlier Cranko took up his work in Stuttgart. Today people in Stuttgart talk a lot about preserving the Cranko heritage and about fortifying the foundation Cranko created. Obviously however, he was much more advanced in his under- standing of the classics than those responsible for ballet in Stuttgart today.

Rather than mounting a production of its own, Stuttgart thought of buying the Kirov’s existing 1952 Sleeping Beauty. How Hans-Peter Doll, himself coming from dramaturgy, and Glen Tetley, who confronts us with futuristic dramaturgy that no one else comprehends, both of them responsible for Stuttgart Ballet, could even think of buying such a dated version of The Sleeping Beauty is incomprehensible to me.

I acknowledge the difficulties internationally renowned choreographers will have when expected to work from a new concept and to collaborate with a dramaturge. In the case of The Sleeping Beauty it must include everything extant of Petipa’s original choreography and it must be as pure as possible. Sooner or later we’ll have to face this if we don’t want to fall back to a pre-Cranko stage of development in Stuttgart and elsewhere.

Ballet people are unaware of how the productions of classics could profit from cooperation with a production dramaturge. Indeed, the ballet classics still have to be revamped for contemporary theater. Only then will they be taken seriously on the intellectual level of the best pro- ductions of someone like Giorgio Strehler, Peter Brook, or Peter Stein. This can happen only when choreographers finally decide to call on adequate dramaturges as collaborators.

Ballet people are unaware of how the productions of classics could profit from cooperation with a production dramaturge. Indeed, the ballet classics still have to be revamped for contemporary theater. Only then will they be taken seriously on the intellectual level of the best pro- ductions of someone like Giorgio Strehler, Peter Brook, or Peter Stein. This can happen only when choreographers finally decide to call on adequate dramaturges as collaborators.

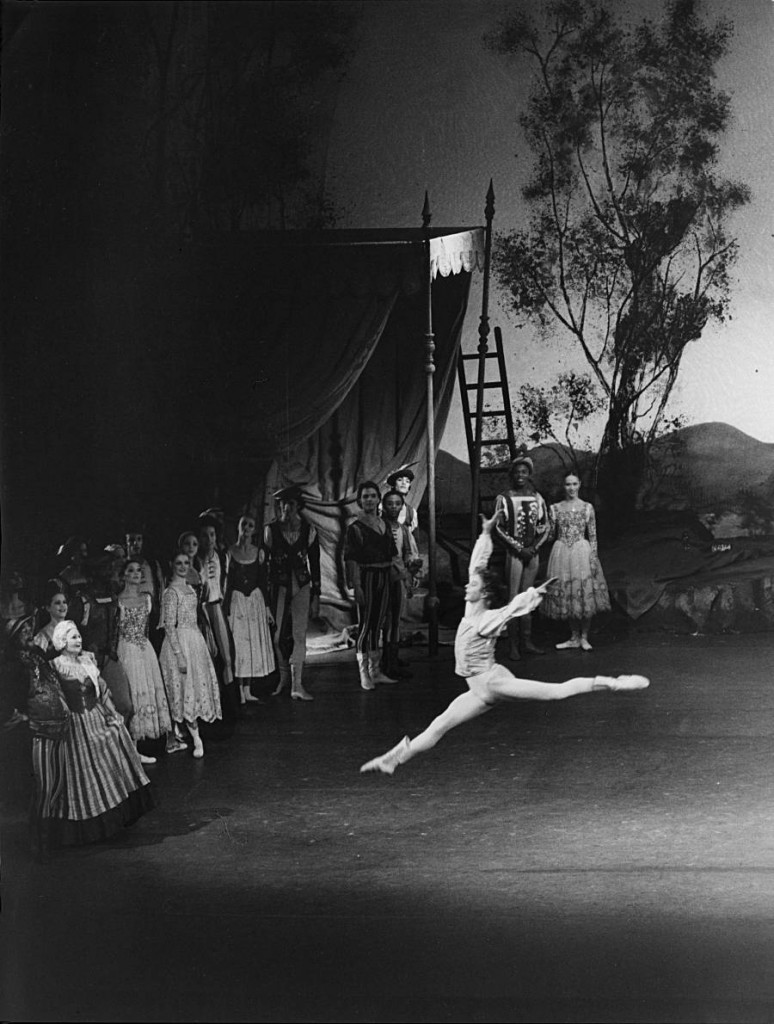

Compared to the innovation of using dramaturgy for ballet classics, as a stimulus for creating new pieces it seems even more important. In that, Cranko was definitely on the right track. he chose this path out of a traditional understanding of ballet. He was the first Western choreographer of our time who realized the need to create new, program-filling works. The results were Onegin, The Taming of the Shrew, and Carmen. There is no doubt that he would have continued on this path, in which case what kind of works might have emerged had he cooperated with a dedicated dramaturge who could have offered him options other than clinging to the literary original?

One is happy to see that Cranko avoided a straightforward reproduction of the Onegin plot at least once, with the so-called “mirror” pas de deux. Less fortunate was his device of having the two women participate in the Lenski-Onegin duel. No playwright or opera librettist would dare to be so unsophisticated today. But these were at least attempts, although they are no models for contemporary ballet, and for musical reasons, too. With all due respect for the effort involved in Kurt-Heinz Stolze’s [composer of Onegin and other Cranko ballets] Tchaikovsky and Scarlatti potpourris, artistically they are not worth mentioning.

When Diaghilev and Massine discovered Pergolesi’s music in archives in Naples, scores that had been totally forgotten, Diaghilev commissioned Stravinsky to compose a new score for Pulcinella. It emerged, despite all of Pergolesi’s inspiration, as an absolutely distinctive Stravinsky ballet score that has proven its viability apart from stage productions. Later, Stravinsky dealt similarly with Tchaikovsky for Le Baiser de la Fée.

When Diaghilev and Massine discovered Pergolesi’s music in archives in Naples, scores that had been totally forgotten, Diaghilev commissioned Stravinsky to compose a new score for Pulcinella. It emerged, despite all of Pergolesi’s inspiration, as an absolutely distinctive Stravinsky ballet score that has proven its viability apart from stage productions. Later, Stravinsky dealt similarly with Tchaikovsky for Le Baiser de la Fée.

Who can imagine the music of Onegin or The Taming of the Shrew as suites acceptable for the concert hall? More likely, Wolfgang Fortner’s score for Cranko’s Carmen might be. Yet the Stuttgart Theater was overly challenged by this score. Why, despite repeated announcements of revivals, have performances of this ballet been kept to an absolute minimum?

In aesthetics and dramaturgy the multiact Cranko ballets are stuck in the nineteenth century. It is an aesthetic that produced questionable works for opera like Gounod’s Faust, Thomas’ Hamlet, and Massenet’s Don Quichotte, but at least they came up with new music back then. Here, too, it is Neumeier who is on the way to taking a crucial step forward. Nobody should blame him for being extremely cautious in this by scheduling new combinations that consist of several pieces, yet reach for dramaturgical coherence.

Neumeier’s program in Frankfurt, “Pictures, 1, 2, 3,” pointed the way, so did his brilliant contraposition of Le Baiser de la Fée and Daphnis and Chloe as Nordic winter dream and Mediterranean summer exaltation. His equally adventurous and persuasive pairing of Gluck’s Don Juan with Sacre made sense as a rumination on the impossibility of love and its consequences. These two ballets suggested a step toward the mulitact, coherent form.

Then, there was his Meyerbeer-Schumann in Hamburg, a tremendous dramaturgical effort. It was only partially successful but did attempt to assemble existing material into a larger, new work of art. Neumeier made it a distinctive statement.  Afterwards he moved sideways: Mahler’s Third Symphony to test this dramaturgical conquest of virgin soil with an unaltered piece of music of exorbitant dimension. One can only admire Neumeier’s wisdom, how he gradually approaches the task of a thematically coherent, evening-length ballet to new music. That, of course, is the goal: a program-filling work arising from the choreo- grapher’s collaboration with a renowned composer of our time.

Afterwards he moved sideways: Mahler’s Third Symphony to test this dramaturgical conquest of virgin soil with an unaltered piece of music of exorbitant dimension. One can only admire Neumeier’s wisdom, how he gradually approaches the task of a thematically coherent, evening-length ballet to new music. That, of course, is the goal: a program-filling work arising from the choreo- grapher’s collaboration with a renowned composer of our time.

Why is there nowhere an attempt, for example, to offer some ballet equivalent to what Bertolt Brecht and Franz Xaver Kroetz (I know that he has written no program-filling piece up to now) or Harold Pinter and Edward Bond have to offer in spoken theater? It’s because there are no ballet dramaturges capable of inventing comparable content and form in collaboration with choreographers. But do we want to give up hope and resign ourselves forever to ballet lagging behind the dramaturgical progress of contemporary theater, and to persuade ourselves that this deficiency is compensated for by the choreographic contribution? For me, No, at least not yet.

Even during Cranko’s era I wasn’t satisfied with this. The crucial point of my criticism of Cranko is that his dramaturgy was stuck in the past. I cannot understand why a man with the education and the knowledge of Walter Erich Schäfer, who has a flair for development in contemporary theater, didn’t help Cranko out of this impasse. My reviews of Cranko have always  been an attempt to lure him out of this dramaturgical attachment to the nineteenth century. Probably I asked too much of him. Presumably Cranko would have needed a dramaturge he trusted, the Diaghilev every choreographer could use. And in this I don’t exclude Balanchine, Ashton, Béjart, MacMillan, Grigorovich, and Neumeier – not even my friend Hans van Manen.

been an attempt to lure him out of this dramaturgical attachment to the nineteenth century. Probably I asked too much of him. Presumably Cranko would have needed a dramaturge he trusted, the Diaghilev every choreographer could use. And in this I don’t exclude Balanchine, Ashton, Béjart, MacMillan, Grigorovich, and Neumeier – not even my friend Hans van Manen.

By the way, I consider van Manen an excellent dramaturge, in some respects ahead of Neumeier – not in terms of the multiact, thematically coherent form, which doesn’t interest him at the moment, or of needed revision of the classics – but in terms of clear and conclusive dramaturgy. For every piece, van Manen sets himself a new thematic and formal task, then realizes it with admirable logic.

I consider dramaturgy as necessary for anecdotal or dramatic storytelling. Van Manen in the single-act form he prefers is simple, clear, and straightforward in his dramaturgy. A shining example of this is the ballet Mutations, for which van Manen choreographed the film sequences, while Tetley was responsible for the stage choreography. The dramatic conception of integrating film and stage was van Manen’s and it’s a shame that it was overlooked, because Mutations was the first respectable nude ballet of the recent past.

For van Manen, a new ballet production is always linked with the dramaturgy, which has to be developed specifically for the piece and topic. He would profit from cooperation with a dramaturge, too, because of the pressure that would be lifted so that he could concentrate on choreographing. However, I don’t believe van Manen would agree with me, because for him dramaturgy and choreography are identical.

A lot of other choreographers will claim that this is the case for them too. Because they are their own dramaturges, they believe they need no further help. But there are very few choreographers able to think dramaturgically, at least like a Neumeier or van Manen who do think that way. Tetley, for example, could make clearer, more understandable, more reasonable and straightforward ballets if he collaborated with a dramaturge.

Undoubtedly, though, he and most of his colleagues don’t want this. They prefer to pose riddles because they don’t want the viewers to realize that they have nothing to say. To be clear and comprehensible the creator must be able to think clearly and understand the content to be conveyed. Tetley I consider to be an important choreographer but an absolutely awful dramaturge, and so are many of his colleagues.

Undoubtedly, though, he and most of his colleagues don’t want this. They prefer to pose riddles because they don’t want the viewers to realize that they have nothing to say. To be clear and comprehensible the creator must be able to think clearly and understand the content to be conveyed. Tetley I consider to be an important choreographer but an absolutely awful dramaturge, and so are many of his colleagues.

In addition to being the thinker-in-charge who lightens the choreographer’s preparatory workload, the dramaturge should also be the program maker, the one who shapes the repertory. This function I consider extraordinarily important, which up to now hasn’t been realized at all abroad, not even in such progressively oriented companies as Netherlands Dance Theater, Ballet Rambert, and London Contemporary Dance Theatre.

In our country, too, few people have understood this necessity, even during the course of Neumeier’s programs in Frankfurt and Hamburg. Such dramaturgy is needed to get away from a meaningless stringing together of unrelated pieces in a triple bill. But “ballet mixed pickles” is the daily fare everywhere.

It has been like this ever since Diaghilev introduced programs of several short ballets. To compile meaningful, correlated, and compatible ballets into a coherent program requires astuteness and imagination, talents that distinguish a dramaturge. To  build a program around a single composer might be the easiest approach, like the Stravinsky ballet evenings one sees everywhere and most recently even in Wuppertal. However, there, Gleede and Pina Bausch almost forced a thematic connection with their “Sacre du Printemps” title. Perhaps not everybody understood it immediately, but Gleede gave convincing reasons for it in the playbill.

build a program around a single composer might be the easiest approach, like the Stravinsky ballet evenings one sees everywhere and most recently even in Wuppertal. However, there, Gleede and Pina Bausch almost forced a thematic connection with their “Sacre du Printemps” title. Perhaps not everybody understood it immediately, but Gleede gave convincing reasons for it in the playbill.

Or take the “Hommage à Balanchine” program of Balanchine and Robbins at the Paris Opera or Béjart’s Boulez program at Ballet of the 20th Century. Of course, such a thematic approach quickly becomes outworn. Variations are certainly possible, like Béjart’s “Suite Viennoise,” in which he presented ballets to music by Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton von Webern.

Also conceivable are deliberate confrontations of composers of different periods. Why not Handel and Brahms, Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky, cori spezzati (divided choirs) pieces of the Venetian School of Andrea Gabrieli and stereo- and quadrophonic pieces by Karlheinz Stockhausen? Why not certain groups like the composers of the Mannheim School or Les Six? One has to have imagination and knowledge. These are only a few principles for arrangement, decidedly musical-dramaturgical. I cannot understand why Düsseldorf, with one of the world’s highest quality ballet-music repertories, doesn’t work more deliberately in this direction.

Yet, preserve us from such programs. After all, a ballet stage is not a dissatisfied concert hall, where dovetailed concert programs are also rare. Neumeier showed that it could be different, that thematic and dramatic links are possible, like his programs with collective titles, “Invisible Boundaries” and “Pictures 1, 2, 3,” or his contrasting winter-summer bill of Le Baiser de la Fée and Daphnis and Chloe or his two variations on the impossibility of love in Don Juan and Sacre. All this should only hint at achieving – even in a program of several pieces – a thematically coherent statement instead of those balletic mixed pickles.

Yet, preserve us from such programs. After all, a ballet stage is not a dissatisfied concert hall, where dovetailed concert programs are also rare. Neumeier showed that it could be different, that thematic and dramatic links are possible, like his programs with collective titles, “Invisible Boundaries” and “Pictures 1, 2, 3,” or his contrasting winter-summer bill of Le Baiser de la Fée and Daphnis and Chloe or his two variations on the impossibility of love in Don Juan and Sacre. All this should only hint at achieving – even in a program of several pieces – a thematically coherent statement instead of those balletic mixed pickles.

There has to be imagination, and if the choreographer isn’t capable of it, there has to be a dramaturge to make this special program concept comprehensible in workshop performances and in the playbill. It would no longer be possible simply to replace one ballet with another, but this is the least problem in our celebrity-centered scheduling.

As for the public benefits of dramaturgy, which should be a service for the audience, it has degenerated to the mere production of playbills and all kinds of flyers, offering not even correct information for the ballet and, because of the sheer inability to say anything about ballet per se, seeking refuge in making wordy, music-theory remarks.

Public relations for dramaturgy are necessary. There are specific tasks regarding ballet dramaturgy, and anyone interested in what can be accomplished should be aware of the Hamburg State Opera’s and Dance Forum Cologne’s workshops and information events. The other type should disappear.

Then there is dramaturgy’s function in regard to repertory. Basically, it is an extension and continuation of program dramaturgy: long-term design of the repertory, aimed at giving the schedule of a company an individual stamp by highlighting specific works. This depends on the choreographers and their choreographies. New York City Ballet, with its all-Balanchine and all-Robbins programs, is naturally the example par excellence. In a somehow different way this is also true of Béjart in Brussels and Neumeier in Hamburg. To a certain extent it was the case at the Stuttgart Ballet during the Cranko era. There can be no talk of this at The Royal Ballet, Paris Opera Ballet, La Scala, or American Ballet Theatre, despite the MacMillan emphasis among the English.

Obviously the emphases of the schedule follow the designated choreographers. In addition to the chief or resident choreographer, a few complementary guest choreographers should be engaged – repeatedly engaged – instead of coming up repeatedly with new guests, only because one of them was successful elsewhere or their name is the flavor of the month.

Obviously the emphases of the schedule follow the designated choreographers. In addition to the chief or resident choreographer, a few complementary guest choreographers should be engaged – repeatedly engaged – instead of coming up repeatedly with new guests, only because one of them was successful elsewhere or their name is the flavor of the month.

In this regard Cranko pursued a very healthy and also a dramaturgic policy by augmenting his own ballets with occasional contributions by Balanchine and MacMillan and no one else. I absolutely cannot discover a common thread or any sense or dramaturgic purpose in the policy of the ballet repertory at Deutsche Oper Berlin, Bavarian State Opera, and Vienna State Opera up to now. In West Berlin, Gert Reinholm’s aim seems to be to welcome into the Deutsche Oper a diaspora of St. Petersburg ballet classicism.

Here in Stuttgart, the policy appears determined by neither dramaturgic nor other identifiable guidelines. It only proceeds from one premiere to the next, neglecting the classics. However, I’m surprised at how the dancers and audience resign themselves readily to this, instead of pressuring the directorate to change this unacceptable situation.

Admittedly, the repertory of a big ballet company is preprogrammed to a large extent with the classics, with pieces by one or more resident choreographers or by amicably associated guest choreographers. For Stuttgart I wish there could be occasional attempts to restore a historical piece, like Ashton did with with La Fille Mal Gardée or The Two Pigeons. I can imagine similar attempts with ballets by Jean-Georges Noverre or Étienne Lauchery in Stuttgart, Ludwigsburg, or Schwetzigen, or a whole series of such attractive historical highlights, not only for the Stuttgart area, but also for Munich, Berlin, and, of course, for Vienna.

Historical knowledge is needed for this and that’s exactly what most of today’s choreographers lack. They can reach back at best to the Don Quixote pas de deux and Giselle. An emphasis such as Bonn places on its continuously cared-for Bournonville repertory is an exception. Even there, a dramaturge with historical knowledge could give the ballet directorate, the choreographer, and the ballet master considerable help.

Historical knowledge is needed for this and that’s exactly what most of today’s choreographers lack. They can reach back at best to the Don Quixote pas de deux and Giselle. An emphasis such as Bonn places on its continuously cared-for Bournonville repertory is an exception. Even there, a dramaturge with historical knowledge could give the ballet directorate, the choreographer, and the ballet master considerable help.

I dream of a dramaturge who develops with a choreographer an entirely new form of ballet, capturing each time a very specific and precisely dated social climate at a defined geographical place – such as Roland Petit delineated in Les Intermittences du Coeur, which deals with the decadent Parisian society of the salons in the fin de siècle surrounding Marcel Proust. This comes full circle back to production dramaturgy.

So there are plenty of tasks for ballet dramaturgy, even if it doesn’t exist. Right now there is no ballet dramaturgy used deliberately as an instrument to support the ballet and finally force it to grow up and develop its inherent potential. Naturally, it is much more convenient simply to live for the moment, from one performance to another, from one premiere to the next, and to let things slide by. I’m still convinced that ballet has yet to discover the chances open to it in the concerted ensemble of the contemporary arts. Dramaturgy could crucially aid in this progress, even if some people consider it only the figment of a frustrated ballet critic’s imagination.

____________________________________________________

A note on Horst Koegler (1927 – 2012) by translator Ilona Landgraf:

Koegler’s opinion of John Cranko changed over the years. He later watched Onegin with much delight and the Tchaikovsky potpourri was no longer a thorn in his side. I’m sure that he would also have revised his statement about choreographing at a desk at home rather than together with dancers in the studio, where the main creative process takes place.

__________________________________________________________________________

The text was published first in Ballet Review, 42.1, Spring 2014.

Audio recording of Horst Koegler’s lecture (by courtesy of Noverre Society, Stuttgart)

| Transcript of Horst Koegler’s lecture (in German) | ||

| Transcript of Horst Koegler’s lecture (in English) | ||

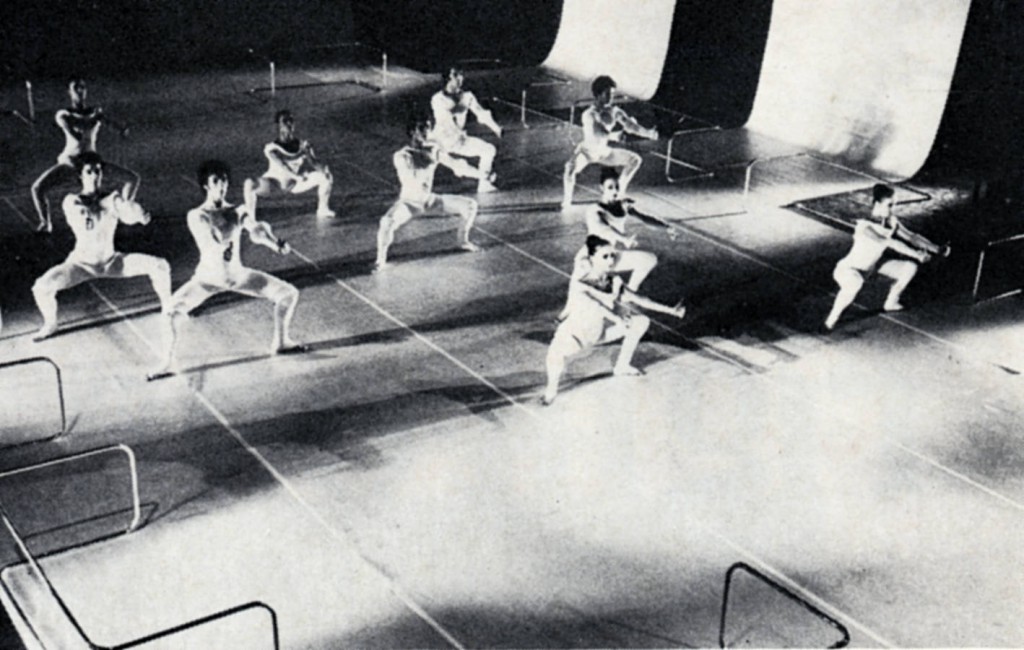

| Photos: | 1. | Horst Koegler ca. 1976, © Gert Weigelt, Cologne |

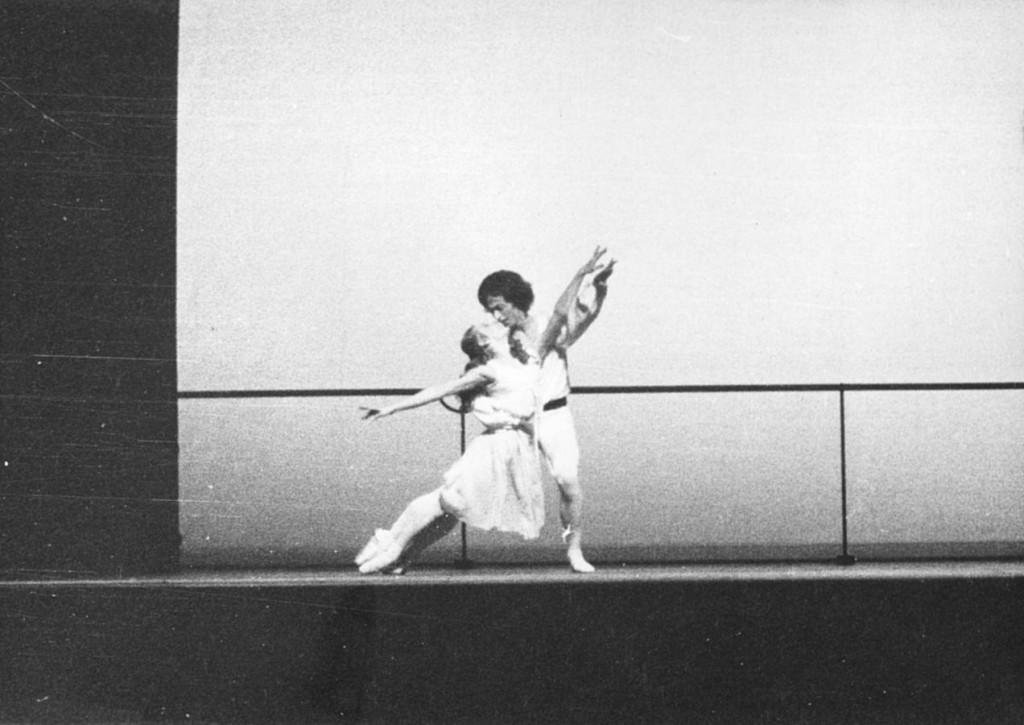

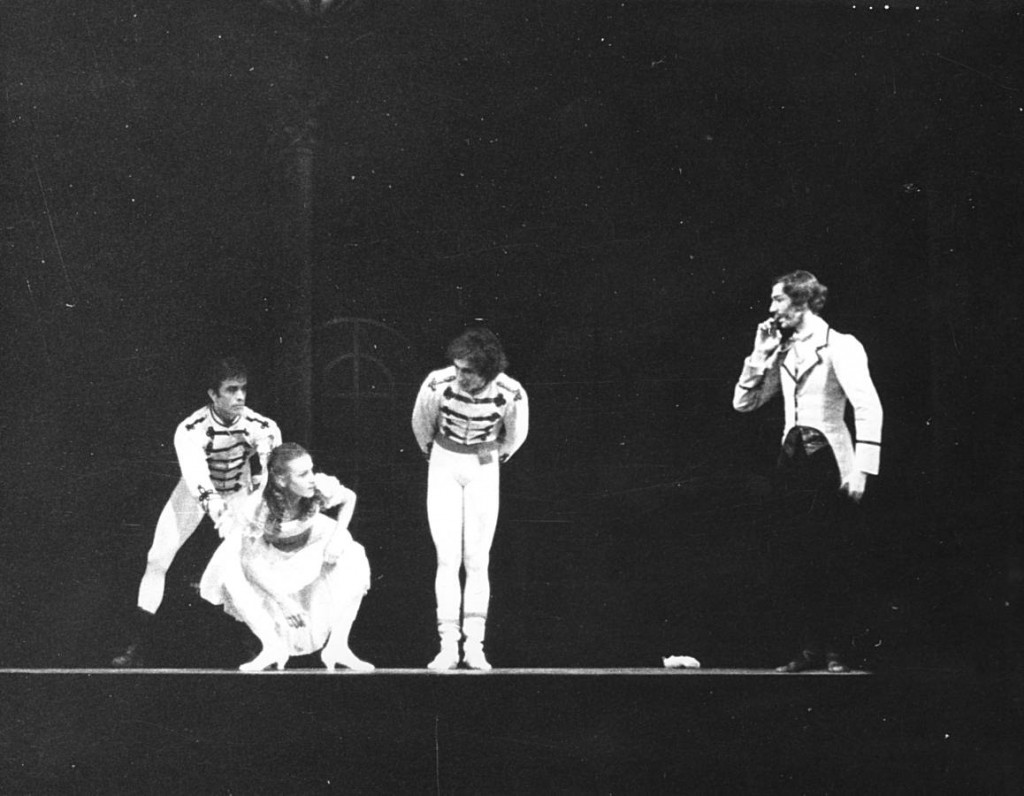

| Choreographies by John Cranko (by courtesy of Noverre Society, Stuttgart) | ||

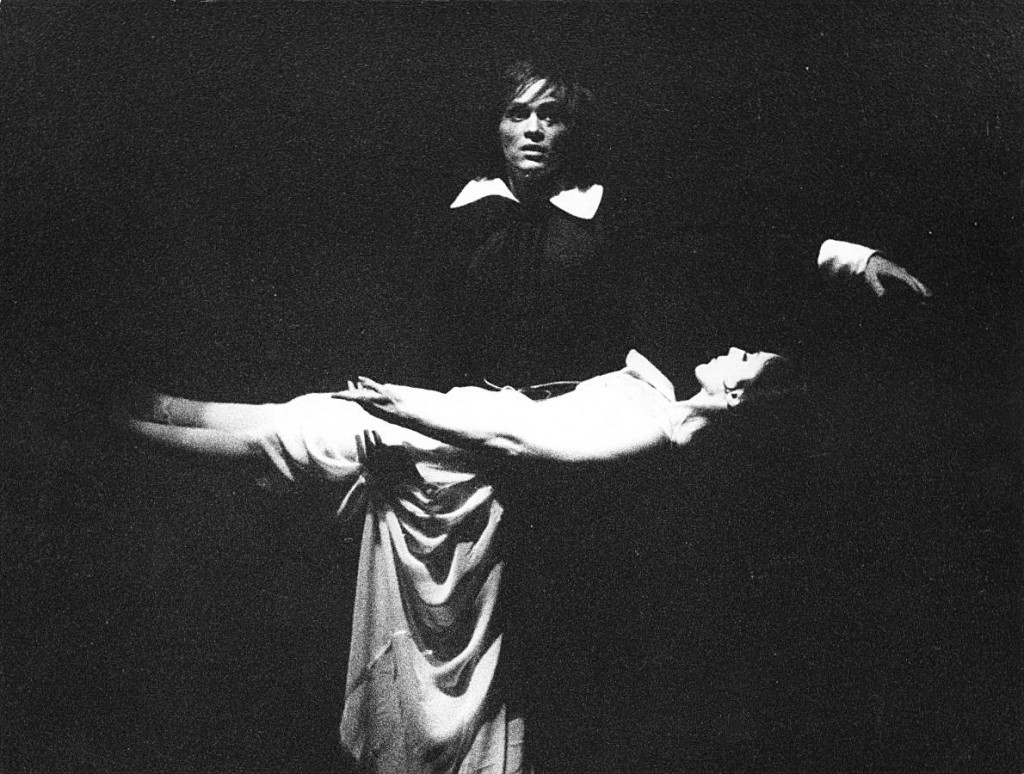

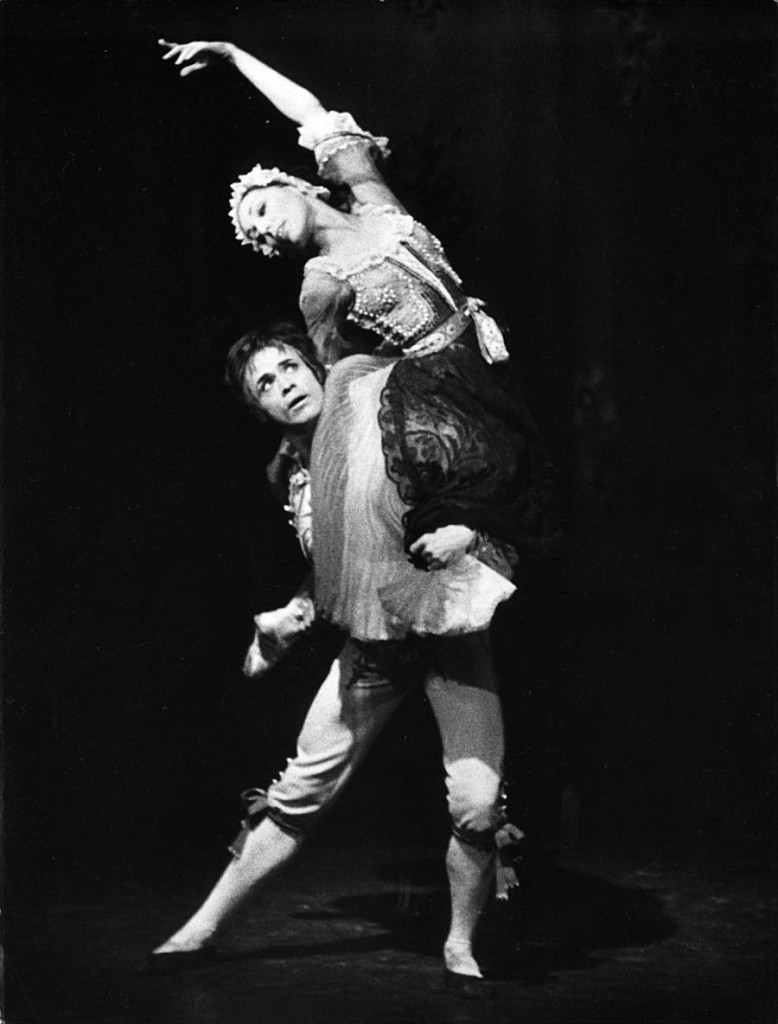

| 2. | Marcia Haydée (Tatiana) and Richard Cragun (Onegin), “Onegin” by John Cranko, Stuttgart Ballet, photo by Leslie E.Spatt © Stuttgart Ballet | |

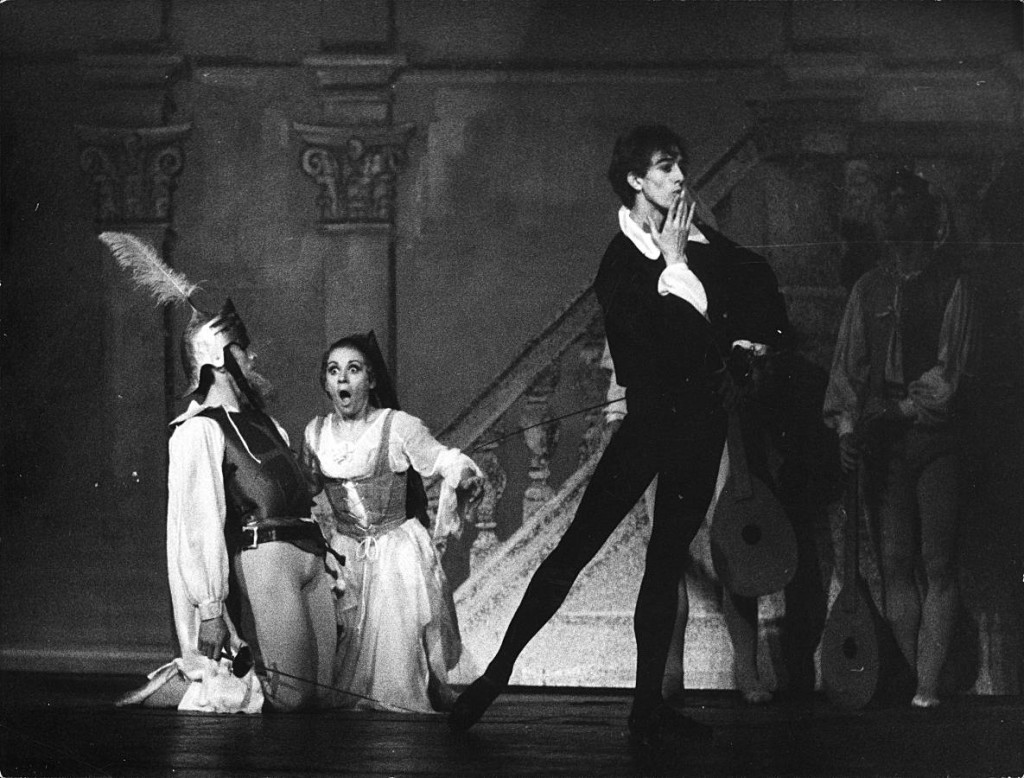

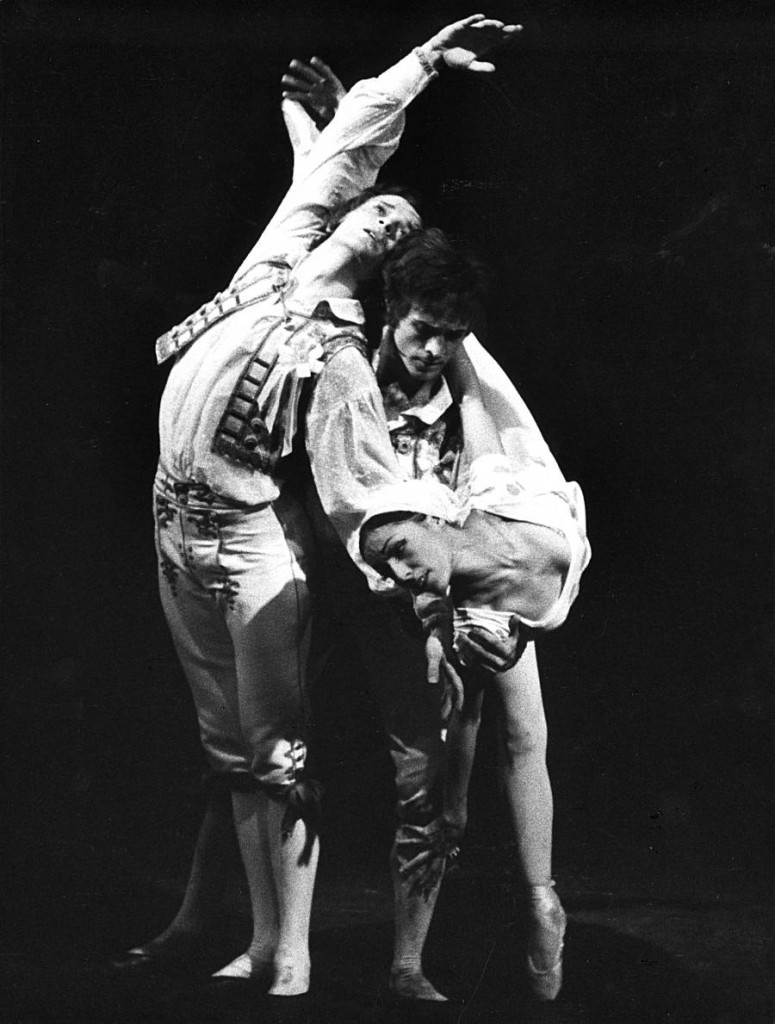

| 3. | Richard Cragun (Petrucchio) and ensemble, world premiere of John Cranko’s “The Taming of the Shrew” in 1969, Stuttgart Ballet, © Hannes Kilian | |

| 4. | Egon Madsen (Prince Siegfried), Hella Heim (Nurse) and ensemble, “Swan Lake” by John Cranko, ca. 1971/72, Stuttgart Ballet, © Hannes Kilian | |

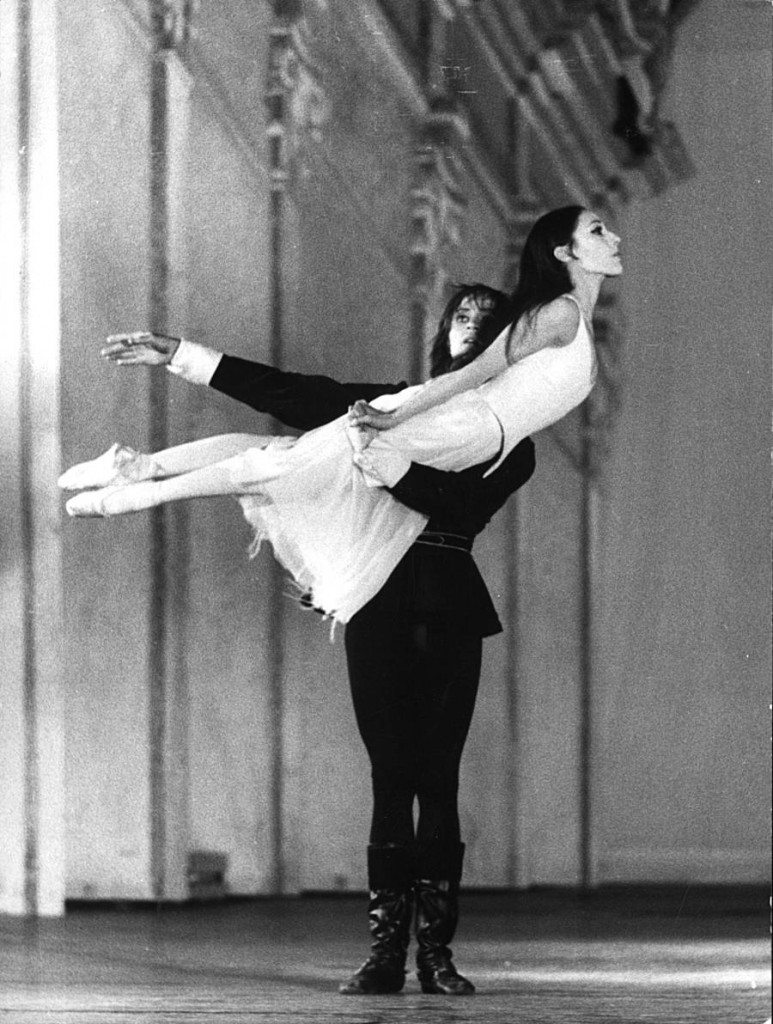

| 5. | Egon Madsen and Marcia Haydée, “The Nutcracker” by John Cranko, ca. 1966, Stuttgart Ballet, © Hannes Kilian | |

| 6. | Lucia Isenring (Tatiana) and Reid Anderson (Onegin), “Onegin” by John Cranko, ca. 1970/71, Stuttgart Ballet, photo by Leslie E.Spatt © Stuttgart Ballet | |

| 7. | Reid Anderson (Escamillo) and ensemble, “Carmen” (Finale) by John Cranko, 1971, Stuttgart Ballet © Hannes Kiian | |

| Choreography by Hans van Manen (by courtesy of the Islington Local History Centre, Finsbury Library) | ||

| 8. | Ensemble of the Nederlands Dans Theatre, “Mutations” by Hans van Manen and Glen Tetley, May 11, 12 and 13, 1973, © Islington Local History Centre, Finsbury Library | |

| Choreographies by John Neumeier (by courtesy of the John Neumeier Foundation, Hamburg) | ||

| 9. | Marianne Kruuse (Marie) and Truman Finney (Günther), “The Nutcracker” by John Neumeier, Ballet Frankfurt, 1971, © John Neumeier Foundation, Hamburg | |

| 10. | Maximo Barra, Marianne Kruuse (Marie), Truman Finney, Max Midinet (Drosselmeier), “The Nutcracker” by John Neumeier, Ballet Frankfurt, 1971, © John Neumeier Foundation, Hamburg | |

| 11. | Truman Finney (second from left), Maximo Barra (fifth from left) and ensemble, “Daphnis and Chloe” by John Neumeier, Ballet Frankfurt, 1972, © German Theater Museum Munich, Archive Fritz Peyer | |

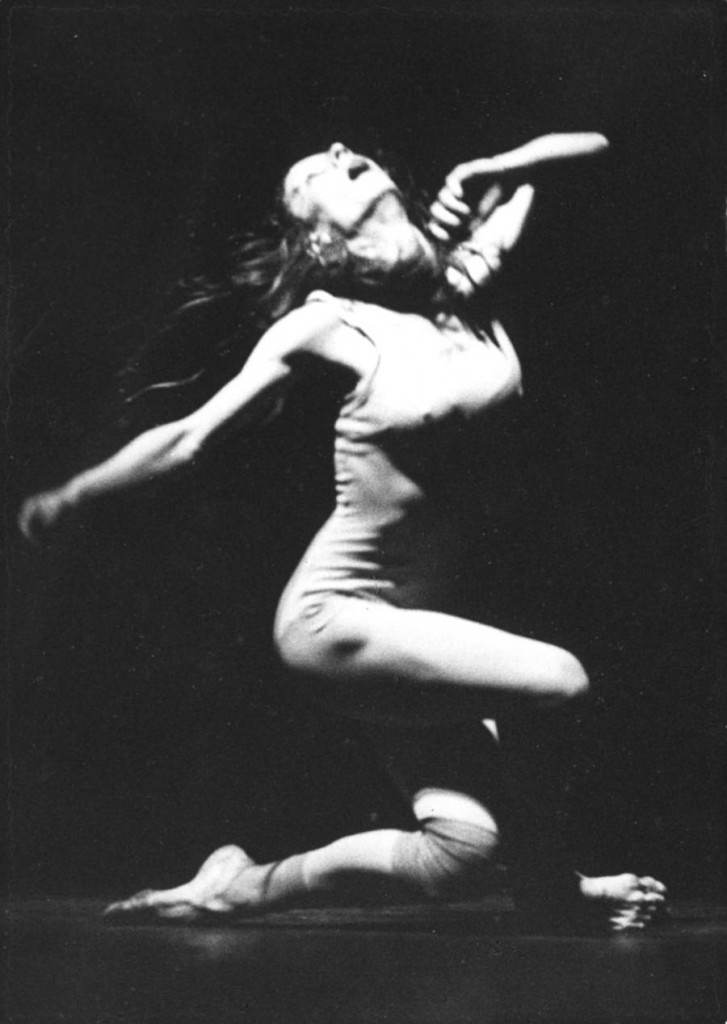

| 12. | Marianne Kruuse, “Daphnis and Chloe” by John Neumeier, Ballet Frankfurt, 1972, © German Theater Museum Munich, Archive Fritz Peyer | |

| 13. | Fred Howald (Don Juan Tenorio) and Persephone Samaropoulo (The Woman in White), “Don Juan” by John Neumeier, Ballet Frankfurt, 1972, © Günther Englert, Frankfurt | |

| 14. | Max Midinet (Catalonón), Marianne Kruuse (Aminta), Fred Howald (Don Juan Tenorio), “Don Juan” by John Neumeier, Ballet Frankfurt, 1972, © Günther Englert, Frankfurt | |

| 15. | Fred Howald (Don Juan Tenorio) and Persephone Samaropoulo (The Woman in White), “Don Juan” by John Neumeier, Ballet Frankfurt, 1972, © Günther Englert, Frankfurt | |

| 16. | Fred Howald, Maximo Barra and Persephone Samaropoulo, “Le Baiser de la Fée” by John Neumeier, 1972, © Günther Englert, Frankfurt | |

| 17. | Persephone Samaropoulo and Fred Howald, “Le Baiser de la Fée” by John Neumeier, 1972, © Günther Englert, Frankfurt | |

| 18. | Beatrice Cordua (The Chosen One), “Le Sacre” by John Neumeier, Ballet Frankfurt, 1972, © Günther Englert, Frankfurt | |

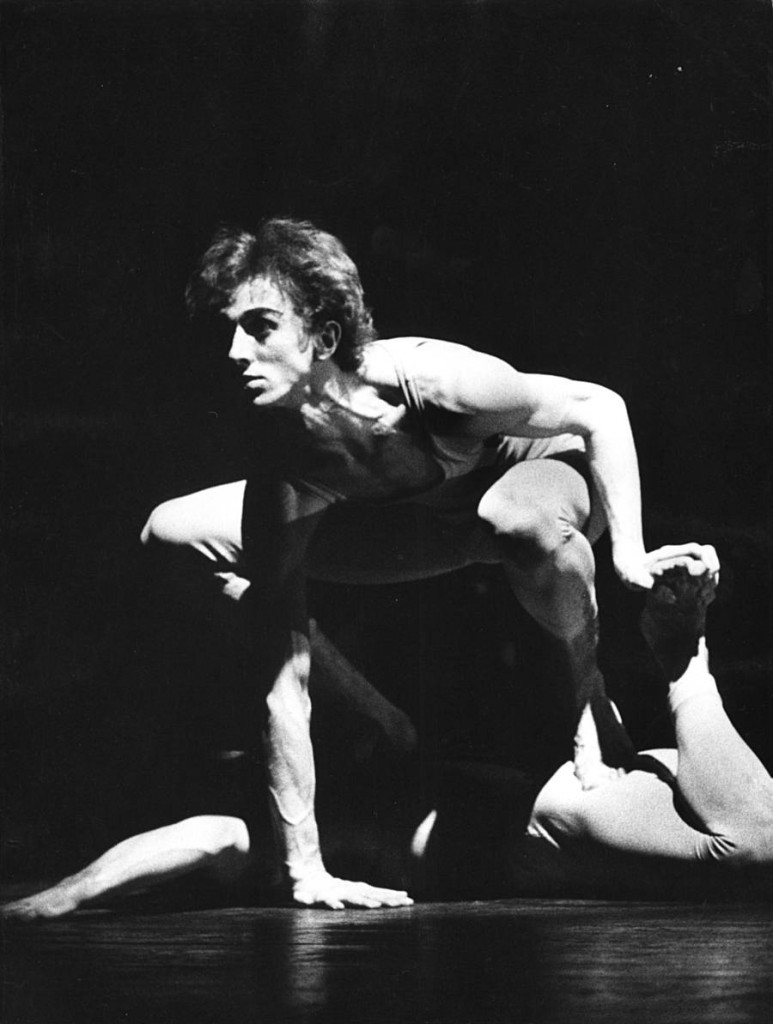

| 19. | Max Midinet, “Le Sacre” by John Neumeier, Ballet Frankfurt, 1972, © Günther Englert, Frankfurt | |

| 20. | Max Midinet and ensemble, “Meyerbeer” by John Neumann, Ballet Frankfurt, 1974, © German Theater Museum Munich, Archive Fritz Peyer | |

| Editing: | George Jackson, Marvin Hoshino | |