“Suite Barocco”, “Syncope”, “Liebe und Tod” (“Love and Death”), “Le Mandarin Merveilleux”

Béjart Ballet Lausanne

Stuttgart State Opera

Stuttgart, Germany

November 27, 2015

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2015 by Ilona Landgraf

As Stuttgart Ballet tours Korea and Japan, the guesting of the Béjart Ballet Lausanne on the last weekend in November was a welcome extra dose of dance for the aficionados in the Stuttgart audience. The troupe presented a mixed bill of four pieces. Three of them had been choreographed by Maurice Béjart, one was created by Gil Roman, the company’s artistic director since Béjart’s death in 2007.

As Stuttgart Ballet tours Korea and Japan, the guesting of the Béjart Ballet Lausanne on the last weekend in November was a welcome extra dose of dance for the aficionados in the Stuttgart audience. The troupe presented a mixed bill of four pieces. Three of them had been choreographed by Maurice Béjart, one was created by Gil Roman, the company’s artistic director since Béjart’s death in 2007.

Béjart’s “Suite Barocco”, a piece from 1997 to vocal Baroque music, has no clear storyline. At the beginning the core figure, Julien Favreau, the cliche of a young, handsome but tragic hero, stands numbly at center stage. Birds are chirping cheerfully; cuckoos can be heard. The moment a duck starts to quack Favreau shoots himself in the head with a pistol. He sinks to the ground and is soon covered by a layer of snow. Colorfully clad dancers (costumes by Gianni Versace and Henri Davila) quickly surround his body like jauntily fluttering birds. Are we perhaps being fast-forwarded to spring? Favreau is maneuvered onto an armchair at the front right corner of the stage. There, the care of two female birds and later of a male bird revives him. Posturing like a chastened thinker, Favreau from then on seems to see the world with different eyes. Or is he dead and we witness what happens to him in the otherworld? Who knows? In any case, he is again interested in what goes on around him. He is infected by the other dancers’ joie de vivre.

When three women in elegantly flowing Asian costumes enter, dancing with two large fans, the atmosphere becomes sacral and dignified. Does that imply that Favreau considers himself better than others? Just when he starts to become complacent and poses on the armchair as if sitting on a throne, he is shoved off. It thunders; it starts to rain, and again a shot strikes him down. Thinking the piece is over, people start to applaud, but, no, another scene follows. Wouldn’t a smart cut have been better than adding idea upon idea?

To depict the character’s experiences during what might be his journey through life, Béjart vacillates between apparent seriousness and overt humor. Favreau’s movement language ranges from brief manly poses to limber postures with bent knees and slouched shoulders. Overall, his dancing has a feminine aspect. At the end, after several attempts to shoot himself, Favreau stands on stage to the accompaniment of Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Gloria in Excelsis Deo”. Apparently he has made his peace with existence.

The second piece, Gil Roman’s “Syncope”, leaves one even more puzzled. It is surreal dance theater, a succession of scenes driven by the rhythmic beats of Citypercussion, a group based in Geneva. A waltz by Chopin concludes the ballet. The term “syncopation” in music means a variety of rhythms involving unexpected accents; in medicine the term signifies a short loss of consciousness. As it turns out, Roman was using both meanings.

An odd couple, Elisabet Ros and Gabriel Arenas Ruiz, are Roman’s connecting elements. Ros first wears a blue suit with calf-length pants reminiscent of a sailor’s uniform. Her white, lampshade-like hat lights up (costumes by Henri Davila). Later, after having swapped the pants for a skirt and doffed the hat she is more feminine. At one point, when Arenas Riuz carries her off the dark stage, her illuminated hat could be a fluorescent jellyfish floating in space. Other surprising effects also hold one’s attention. Arenas Ruiz sits a few times in an armchair, rolled around by Ros as if it were a wheelchair. He looks as though he has been beamed to another world, paralyzed like a boy who has watched science fiction movies for far too long. His hair sticks out as if electrified. Twice the armchair sucks him into itself. With eyes wide open in amazement, he disappears into a mysterious hole in the backrest and then finds himself lying on the floor behind. He clings to Ros like mamma’s boy but later dares to become acquainted with a bird-like woman (Alanna Archibald). Is he spreading his own wings? Though the bird-woman’s dance radiates proud self-assurance, she later perches herself safely in a wooden bird cage again.

Roman invented sweeping group dances that reflect every beat of the music. Like Béjart in “Suite Barocco”, he also includes a short moment of silence. And like Béjart he fails to find an ending. Several times one expects the curtain to come down but flickering strobe lights or a new prop appearing herald a continuation. After all these fireworks of surprises and gags, one wonders what trump card Roman will come up with to actually finish. Answer: he draws on the Chosen One’s final solo in Nijinsky’s “Le Sacre du printemps”. Roman’s dancers line up and sprint until Arenas Ruiz collapses. When he regains consciousness and suddenly sits up with a gasp, “Syncope” is over.

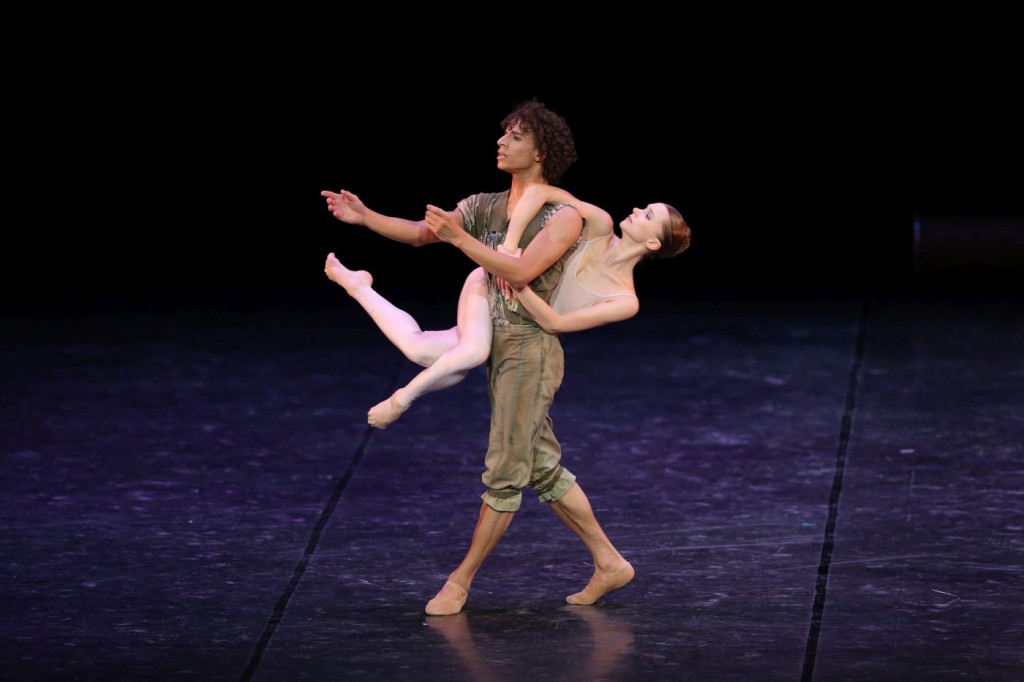

Two Bejart pieces were presented after the intermission. “Liebe und Tod” (“Love and Death”), a pas de deux from 2002, is set to two songs of Gustav Mahler’s song cycle “Des Knaben Wunderhorn” (“Youth’s Magic Horn”). One, “Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen” was reworked to “La Mort du Tambour”; the second song, “Der Tamboursg’sell”, is unmodified. Béjart tells the story of a soldier, a tambour player (Oscar Chacon), who develops a tender romance with a girl (Kateryna Shalkina). Initially the floor is lit red, as though soaked with the blood of fallen comrades. When the love affair unfolds, the red light shines on their bodies like an intense aurora. The song’s actual lyrics about a house on a green heath, are not visualized on stage. At the end, the soldier lies dead on the ground. “Liebe und Tod” is an inherently consistent, unpretentious piece; the story is told in a straightforward manner and is devoid of any extras. It works.

Two Bejart pieces were presented after the intermission. “Liebe und Tod” (“Love and Death”), a pas de deux from 2002, is set to two songs of Gustav Mahler’s song cycle “Des Knaben Wunderhorn” (“Youth’s Magic Horn”). One, “Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen” was reworked to “La Mort du Tambour”; the second song, “Der Tamboursg’sell”, is unmodified. Béjart tells the story of a soldier, a tambour player (Oscar Chacon), who develops a tender romance with a girl (Kateryna Shalkina). Initially the floor is lit red, as though soaked with the blood of fallen comrades. When the love affair unfolds, the red light shines on their bodies like an intense aurora. The song’s actual lyrics about a house on a green heath, are not visualized on stage. At the end, the soldier lies dead on the ground. “Liebe und Tod” is an inherently consistent, unpretentious piece; the story is told in a straightforward manner and is devoid of any extras. It works.

In “Le Mandarin Merveilleux” (“The Miraculous Mandarin”), Béjart interprets Béla Bartók’s so-titled pantomime ballet which was banned on moral grounds after its premiere in 1926. It is about three pimps forcing a young girl to entice clients whom they then rob. The third client is a mysterious mandarin. The pimps try three times to kill him but, wounded, his desire for the girl keeps him miraculously alive. Only after the pimps throw his body into the girl’s arms does he die.

In Béjart’s version a gang led by their slick chief (Julien Favreau) robs with the help of a sexy lure. Lawrence Rigg is the prostitute, a blonde androgynous vamp in a black patent leather bodice embellished with black feathers around the shoulders. A little feather tail and feathery bunch at the crotch hint at a Faun’s costume.

The story plays out in a disreputable, dim and smoky room whose only piece of furniture is a table on steel tube legs. Later the mandarin is attacked in a backyard or perhaps out on a side road that has the same unpleasant atmosphere. Stage design is by Christian Frapin. Anna De Giorgi designed the costumes after Fritz Lang’s in the 1927 silent film “Metropolis”. The chief gangster, wearing a pinstripe suit and black leather gloves, keeps his hands clean. Though his black tie flies out during the fights with the mandarin, he sticks to his role as the hands-off boss. The prostitute’s first victim, Siegfried (Connor Barlow), wearing only a loincloth and boots made of fur, seems to be a hero from prehistoric times. Her second client is a shy young man but, be careful, this part is danced by a woman (Lisa Cano): again a gender twist. The third victim, Masayoshi Onuki, is the tough mandarin with superhuman strength. Neither stabbing with a knife nor hanging nor physical abuse by the mob can harm him. Again and again he stands back up, always looking unscathed.

“Le Mandarin Merveilleux” is a gripping gangster piece, an edgy study of the sleazy lowlife. Rigg is excellent as the prostitute, playing the dominant manipulator and seducer of her victims. Though the chief’s moll, she in fact is under his thumb. The only weak scene was the end. Rigg, up to then having short, gelled-back hair, suddenly appears wearing a blonde, curly wig. She throws it disdainfully at the mandarin’s feet. He lies down on it and, in ecstasy, thrusts his pelvis towards it. This borrowing from Nijinsky was not a good idea. It left one with a sour taste after an otherwise entertaining evening.

Béjart’s style is well-known in Stuttgart since Marcia Haydée took several of his pieces into the company’s repertory when she became director in 1976. Stuttgart responded to the troupe from Lausanne with cheers.

| Links: | Homepage of the Béjart Ballet Lausanne | |

| Stuttgart Ballet’s Homepage | ||

| Photos: | 1. | Alanna Archibald and Gabriel Arenas Ruiz, “Syncope” by Gil Roman, Béjart Ballet Lausanne 2015 © Ilia Cholnik 2015 |

| 2. | Kateryna Shalkina and Oscar Chacon, “Liebe und Tod” (“Love and Death”) by Maurice Béjart, Béjart Ballet Lausanne 2015 © Kiyonori Hasegawa 2015 | |

| 3. | Ensemble, “Le Mandarin Merveilleux” by Maurice Béjart, Béjart Ballet Lausanne 2015 © Philippe Pache 2015 | |

| Editing: | Laurence Smelser, George Jackson |