“21st-Century Choreographers”

(“Within the Golden Hour” / Optional Family: A Divertissement” / “The Statement” / “Solo Echo”)

The Royal Ballet

Royal Opera House

London, Great Britain

May 28, 2021 (online)

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2021 by Ilona Landgraf

Over half a year ago, pandemic-related restrictions forced the Royal Opera House to close its doors. On May 18th, a limited audience was finally welcomed back to see the company live on stage. The program – “21st-Century Choreographers” – consisted of four pieces: “Within the Golden Hour” by Christopher Wheeldon; “Optional Family: A Divertissement” – a new piece by Kyle Abraham; and two pieces by Crystal Pite: “The Statement” and “Solo Echo”.

Over half a year ago, pandemic-related restrictions forced the Royal Opera House to close its doors. On May 18th, a limited audience was finally welcomed back to see the company live on stage. The program – “21st-Century Choreographers” – consisted of four pieces: “Within the Golden Hour” by Christopher Wheeldon; “Optional Family: A Divertissement” – a new piece by Kyle Abraham; and two pieces by Crystal Pite: “The Statement” and “Solo Echo”.

I watched the broadcast on May 28th; it is available on demand on the company’s website until June 27th.

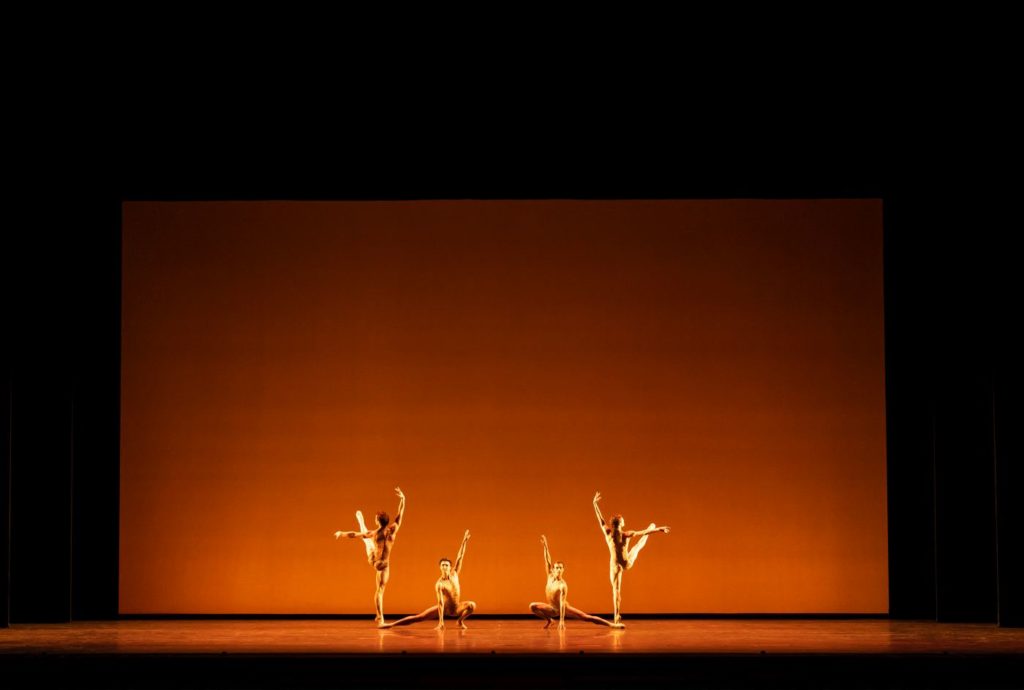

Wheeldon’s “Within the Golden Hour”, originally created for the San Francisco Ballet in 2008, is a seven-part piece danced by three couples (Anna Rose O’Sullivan & Vadim Muntagirov / Francesca Hayward & Valentino Zucchetti / Yasmine Naghdi &  Ryoichi Hirano) and a small corps of eight. Although its title suggests otherwise, it’s only about a half hour long.

Ryoichi Hirano) and a small corps of eight. Although its title suggests otherwise, it’s only about a half hour long.

String music by Ezio Bosso and Antonio Vivaldi anchors each part in a unique atmosphere that is mirrored by dance that is in turn super-fast, slow, emotional, serene, energetic, earnest, and playful. The stage is black except for a strip of lighting above the floor that evokes the warm light of the sun as it sits low atop the horizon. It shifts between purple, blue, and red. As the strip of light widens, the floor is bathed in light too. The costumes (by Jasper Conran) – dresses with lightweight skirts for the women and skintight short pants and tricots for the men – shimmer in gold, white, metallic, or yellow-green depending on the lighting. They contrast strongly with the background, highlighting each movement and emphasizing the geometric patterns of the choreography.

Group dances, duets, and pas de deux are seamlessly intertwined. Two men dash through a rousing duet that combines supple power with precision and speed. Naghdi, supported by Hirano, turns like an ice-skater, holding her calf, leg stretched

up and out. In a playful pas de deux, Muntagirov lifts O’Sullivan, who kicks her legs forward, feet flexed, as if feigning obstinacy. Hayward and Zucchetti’s slow pas de deux nurtures the comfort and care of a trustful, close relationship. Occasionally, the men hop side-to-side on all fours or jump, Puck-like, onto the stage. At one point, supporting themselves with a hand on the floor, three men reach their bottoms pertly out towards the audience. At another, the women perch teasingly on their partners necks, stretching and bending their legs. Standing in a deep plié, couples quickly rotate their upper bodies in opposite directions. Female dancers were lifted as they crossed the stage, bending their legs in a diamond shape and stretching their arms and legs wide. One section featured a feast of arm movements: gentle patting of the upper arm with the fingers of the other hand; closing and opening of the chest while the arms are held rectangularly; resting of one forearm on top of the other as in folk dances.

up and out. In a playful pas de deux, Muntagirov lifts O’Sullivan, who kicks her legs forward, feet flexed, as if feigning obstinacy. Hayward and Zucchetti’s slow pas de deux nurtures the comfort and care of a trustful, close relationship. Occasionally, the men hop side-to-side on all fours or jump, Puck-like, onto the stage. At one point, supporting themselves with a hand on the floor, three men reach their bottoms pertly out towards the audience. At another, the women perch teasingly on their partners necks, stretching and bending their legs. Standing in a deep plié, couples quickly rotate their upper bodies in opposite directions. Female dancers were lifted as they crossed the stage, bending their legs in a diamond shape and stretching their arms and legs wide. One section featured a feast of arm movements: gentle patting of the upper arm with the fingers of the other hand; closing and opening of the chest while the arms are held rectangularly; resting of one forearm on top of the other as in folk dances.

Golden hour occurs at dawn and dusk – and this one certainly marked a dawn. One could sense even through the screen how much the dancers enjoyed the applause.

“Optional Family: A Divertissement” by Abraham begins with a female voice that sounds from the loudspeakers: “My  dearest Richard, when I think of the past twenty-five years we spent together (…)” Is it an affectionate speech from a silver wedding anniversary? Listen further: “If I had listened to my mother and married a man with substance (…) you bore me, you wholeheartedly bore me to no end.” Richard’s reply is just as piercing: “Dearest Emely, thank you for all that you’ve given me over the years: heartburn, three ungrateful children, an insurmountable load of debt…”

dearest Richard, when I think of the past twenty-five years we spent together (…)” Is it an affectionate speech from a silver wedding anniversary? Listen further: “If I had listened to my mother and married a man with substance (…) you bore me, you wholeheartedly bore me to no end.” Richard’s reply is just as piercing: “Dearest Emely, thank you for all that you’ve given me over the years: heartburn, three ungrateful children, an insurmountable load of debt…”

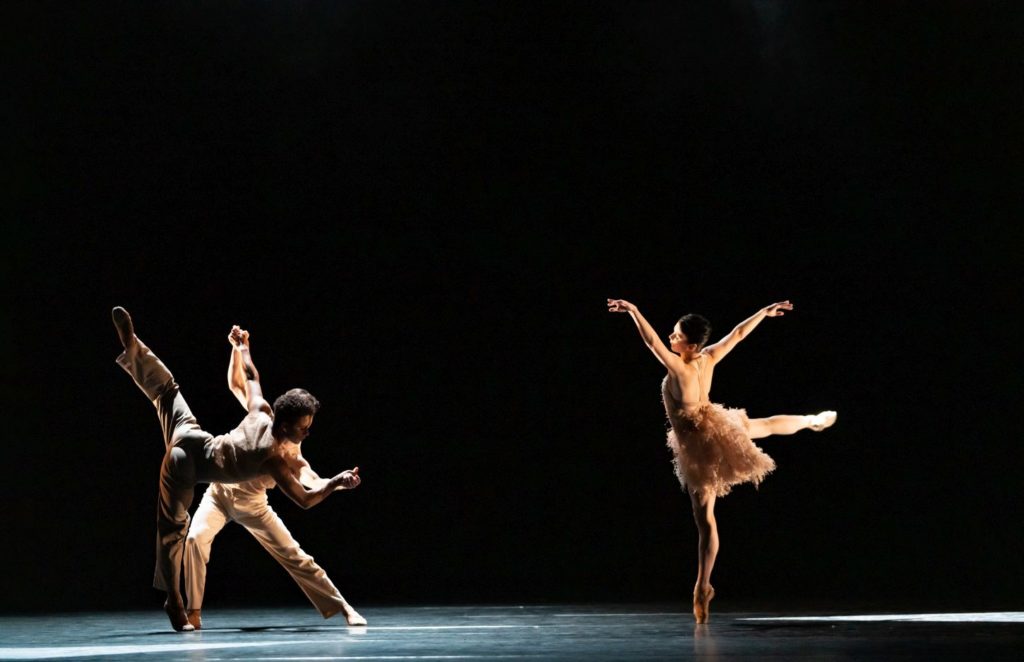

The stage is dark and a telephone rings – but no, the ringing is part of the music, soon joined by clattering metallic sounds,

rhythmic squeaking, and monotonous electronica (music by Nídia Borges and Grischa Lichtenberger). Emely (Natalia Osipova) and Richard (Marcelino Sambé) enter the scene, illuminated against the black floor by triangular patches of light. These spotlights later act as little islands that symbolize family relationship, and later as stepping stones for Stanislaw Węgrzyn’s entrance as the couple’s son – an identity that becomes evident only later. Emely and Richard’s

rhythmic squeaking, and monotonous electronica (music by Nídia Borges and Grischa Lichtenberger). Emely (Natalia Osipova) and Richard (Marcelino Sambé) enter the scene, illuminated against the black floor by triangular patches of light. These spotlights later act as little islands that symbolize family relationship, and later as stepping stones for Stanislaw Węgrzyn’s entrance as the couple’s son – an identity that becomes evident only later. Emely and Richard’s

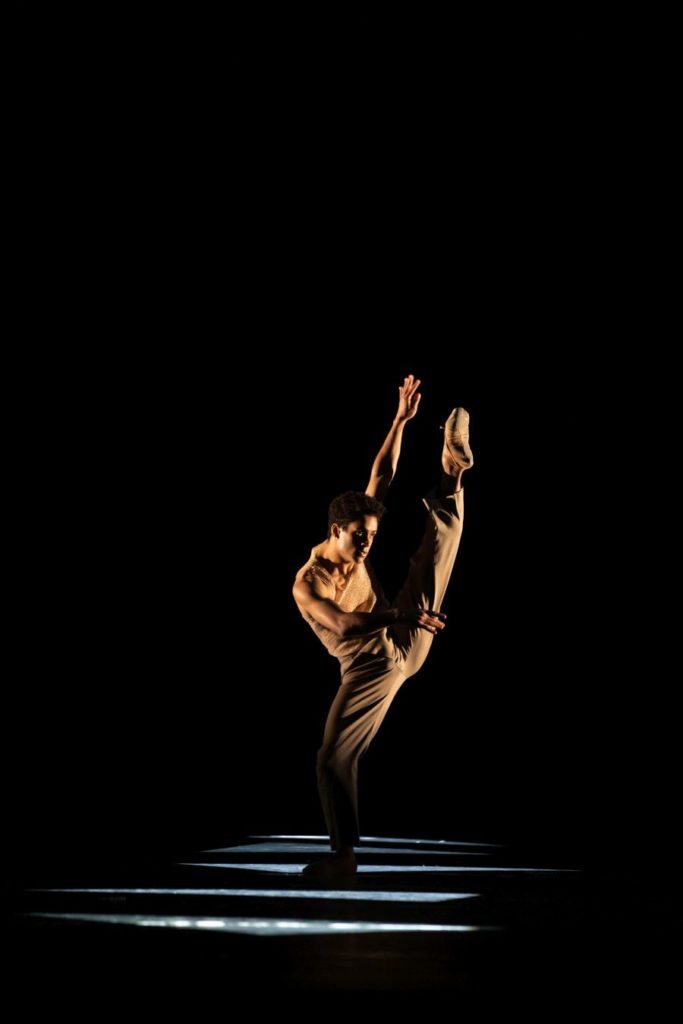

dysfunctional relationship is a constant competition instigated by Emely, who swirls around overactively, oozing the aggressive dominance of an alpha. Richard parries her challenges with salvos of jumps and pirouettes, always in the right spot at the right time to partner with her, never wearing the pants (although he in fact wears pants – designed by Ilaria Martello; ironically, the skirt of Emely’s dress resembles a mop). Their son has inherited his mother’s mania and copies his father’s behavior – but, to Emely’s displeasure, he’s different, too, and in search of himself. She picks a quarrel with Richard over this difference, pushing him out of the family and subsequently abandoning her son. He desperately stretches his arms towards the void before burying his head beneath his hands.

dysfunctional relationship is a constant competition instigated by Emely, who swirls around overactively, oozing the aggressive dominance of an alpha. Richard parries her challenges with salvos of jumps and pirouettes, always in the right spot at the right time to partner with her, never wearing the pants (although he in fact wears pants – designed by Ilaria Martello; ironically, the skirt of Emely’s dress resembles a mop). Their son has inherited his mother’s mania and copies his father’s behavior – but, to Emely’s displeasure, he’s different, too, and in search of himself. She picks a quarrel with Richard over this difference, pushing him out of the family and subsequently abandoning her son. He desperately stretches his arms towards the void before burying his head beneath his hands.

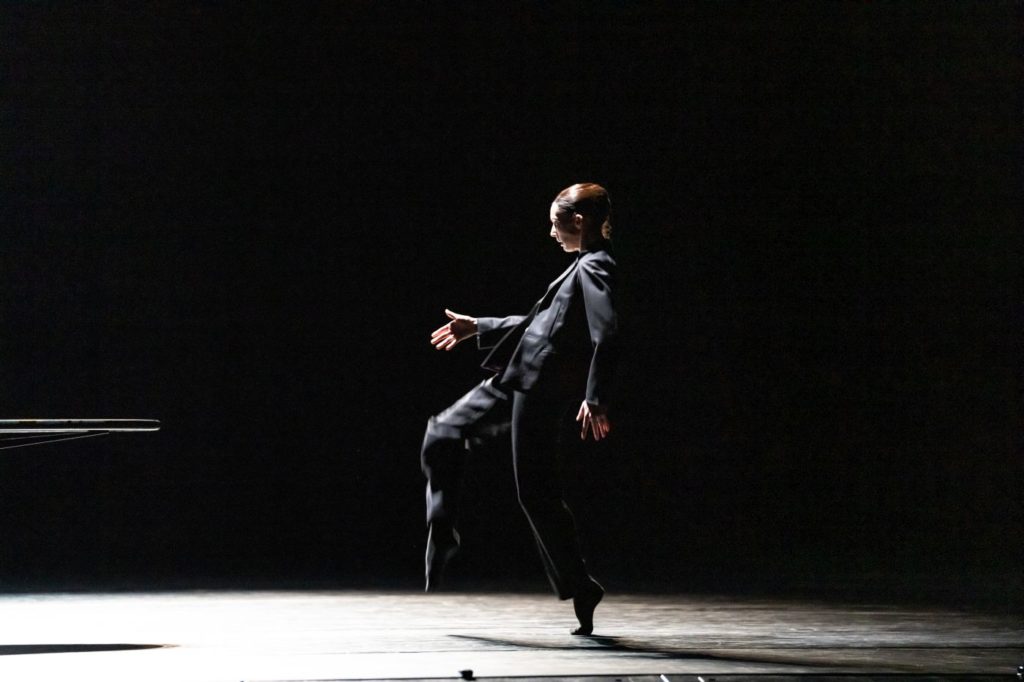

In “The Statement”, created for Nederlands Dans Theater 1 in 2016, Pite takes us to the site of the murky behind-the-scenes wheelings and dealings of an unnamed government or international company. Four businesspeople meet at a shiny oval conference table in a twilit basement room (set by Jay Gower Taylor, lighting by Tom Visser). Their heated conversation – expressed both through recorded dialogue by Jonathan Young from the speakers and through the dancers’ corresponding gestures, facial expression, and movement – is menacing from every angle.

In “The Statement”, created for Nederlands Dans Theater 1 in 2016, Pite takes us to the site of the murky behind-the-scenes wheelings and dealings of an unnamed government or international company. Four businesspeople meet at a shiny oval conference table in a twilit basement room (set by Jay Gower Taylor, lighting by Tom Visser). Their heated conversation – expressed both through recorded dialogue by Jonathan Young from the speakers and through the dancers’ corresponding gestures, facial expression, and movement – is menacing from every angle.

Two of the four (Ashley Dean and Joseph Sissens) belong to a department, while the other two (Kristen McNally and Calvin Richardson) are from “upstairs” – i.e. the higher echelons. An attempt to economically exploit an international conflict has veered off course, leaving the quartet in the soup. “Oh God! … They’re killing each other,” moans the guilt-stricken Dean. Sissens unsuccessfully tries to calm her. Richardson has been sent from

Two of the four (Ashley Dean and Joseph Sissens) belong to a department, while the other two (Kristen McNally and Calvin Richardson) are from “upstairs” – i.e. the higher echelons. An attempt to economically exploit an international conflict has veered off course, leaving the quartet in the soup. “Oh God! … They’re killing each other,” moans the guilt-stricken Dean. Sissens unsuccessfully tries to calm her. Richardson has been sent from  “upstairs” to “fix” the problem – which, in this case, means getting the department to publicly declare its responsibility for the violent escalation, leaving upstairs with clean hands. “They’re expecting the truth,” Richardson claims – but “what is that?” Sissens asks.

“upstairs” to “fix” the problem – which, in this case, means getting the department to publicly declare its responsibility for the violent escalation, leaving upstairs with clean hands. “They’re expecting the truth,” Richardson claims – but “what is that?” Sissens asks.

At first, McNally maintains a low profile while tracking whether their conversation is off- or on-record. Eventually, though, she loosens her belt and is ready to throw Richardson to the wolves. As threats, accusations of blame, and strategic manipulation circle one another, we begin to hear a voiceover instead of the recording. Richardson – by now the scapegoat – re-enacts Dean’s moral struggle. Dean and Sissens, whose heads are spinning, crouch is if caged (in fact they’ve only crawled below the table). As the parties continue to rip into each other, we can hear a cacophony of rattling shots build (music by Owen Belton).

“We didn’t know the whole thing would blow up.” It did. A voice belonging to “upstairs” reassures Richardson that “it’s OK … the situation is gonna resolve itself.”

“We didn’t know the whole thing would blow up.” It did. A voice belonging to “upstairs” reassures Richardson that “it’s OK … the situation is gonna resolve itself.”

Pite created exaggerated movements that trenchantly accentuate the spoken words. The choreography would suit a comedy if it wasn’t all so uncomfortably close to reality.

Pite’s second piece, the 2012 “Solo Echo”, also premiered at Nederlands Dans Theater 1. It’s inspired by Mark Strand’s melancholic poem “Lines for Winter” and is divided into two parts, each accompanied by a plaintive Brahms sonata for cello and piano (Opus 38 and 99). Gentle snow flutters down on three women and four men, all wearing black pants and outdoor vests that obscure everything but arms and faces. Lighting designer Tom Visser took the poem’s line “inside the dome of dark” literally.

Strand’s poem essentially explores themes of cold, stuck-ness, limited knowledge, self-love, and death. Pite translates these themes into tense, edgy, occasionally frenzied movements that project pugnacious strength and an obsessive readiness to get up when one falls. The dancers dart from one side of the stage to the other as if crossing the unprotected area between two military trenches. They bump into each other, topple, and are sometimes caught before touching the ground. They flail about, crawl on their knees, pose with puffed-up chests, jump Spartacus-like from standing, and feel their way through the dark, hands cautiously outstretched. The duets resemble duels or rescue operations. In one moment, a romance seems to blossom, but the quasi-lovers sabotage one another.

Strand’s poem essentially explores themes of cold, stuck-ness, limited knowledge, self-love, and death. Pite translates these themes into tense, edgy, occasionally frenzied movements that project pugnacious strength and an obsessive readiness to get up when one falls. The dancers dart from one side of the stage to the other as if crossing the unprotected area between two military trenches. They bump into each other, topple, and are sometimes caught before touching the ground. They flail about, crawl on their knees, pose with puffed-up chests, jump Spartacus-like from standing, and feel their way through the dark, hands cautiously outstretched. The duets resemble duels or rescue operations. In one moment, a romance seems to blossom, but the quasi-lovers sabotage one another.

In the second half, the dancers build a chain by linking their arms, supporting, ejecting and reincorporating individuals. The undulating knot of bodies soon becomes a dog-eat-dog fight, during which the raging Harry Churches is held back by the others even as he begins to silently scream. Finally, the dancers stand in a line and drop down one by one. Marcelino Sambé, the last in the row, drops too – missing the outstretched arms of the woman ready to catch him.

| Links: | Website of the Royal Ballet | |

| Photos: | 1. | Artists of the Royal Ballet, “Within the Golden Hour” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Royal Ballet 2021 |

| 2. | Artists of the Royal Ballet, “Within the Golden Hour” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 3. | Yasmine Naghdi and Ryoichi Hirano, “Within the Golden Hour” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 4. | Valentino Zucchetti and Francesca Hayward, “Within the Golden Hour” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 5. | Marcelino Sambé and Natalia Osipova, “Optional Family: A Divertissement” by Kyle Abraham, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 6. | Stanislaw Węgrzyn, Marcelino Sambé, and Natalia Osipova, “Optional Family: A Divertissement” by Kyle Abraham, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 7. | Marcelino Sambé and Stanislaw Węgrzyn, “Optional Family: A Divertissement” by Kyle Abraham, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 8. | Marcelino Sambé, “Optional Family: A Divertissement” by Kyle Abraham, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 9. | Stanislaw Węgrzyn and Natalia Osipova, “Optional Family: A Divertissement” by Kyle Abraham, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 10. | Joseph Sissens, Ashley Dean, Calvin Richardson, and Kristen McNally, “The Statement by Crystal Pite, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 11. | Ashley Dean and Joseph Sissens, “The Statement by Crystal Pite, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 12. | Kristen McNally, “The Statement by Crystal Pite, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 13. | Joseph Sissens, Calvin Richardson, and Ashley Dean, “The Statement by Crystal Pite, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 14. | Kristen McNally and Calvin Richardson, “The Statement by Crystal Pite, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 15. | Ashley Dean and Joseph Sissens, “The Statement by Crystal Pite, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 16. | Francesca Hayward and Cesar Corrales, “Solo Echo” by Crystal Pite, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 17. | Francesca Hayward and artists of the Royal Ballet, “Solo Echo” by Crystal Pite, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| 18. | Harry Churches and artists of the Royal Ballet, “Solo Echo” by Crystal Pite, The Royal Ballet 2021 | |

| all photos © Bill Cooper | ||

| Editing: | Jake Stepansky |