Fabien Voranger

Dresden, Germany

October, 2015

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2015 by Ilona Landgraf

Love guided and catalyzed Fabien Voranger’s career in several decisive situations. Just aged ten, being infatuated with a young girl fueled his interest in ballet and led to his audition for the Ballet School of the Paris Opera; and, as it happens, he was accepted. Later, while he was in a scholarship study program at the Royal Ballet School in London his girlfriend was his major support during a reorientation forced by injury. Love almost made him follow a ballerina to Australia. His desire to express his art led to many moves but ultimately to success.

Love guided and catalyzed Fabien Voranger’s career in several decisive situations. Just aged ten, being infatuated with a young girl fueled his interest in ballet and led to his audition for the Ballet School of the Paris Opera; and, as it happens, he was accepted. Later, while he was in a scholarship study program at the Royal Ballet School in London his girlfriend was his major support during a reorientation forced by injury. Love almost made him follow a ballerina to Australia. His desire to express his art led to many moves but ultimately to success.

Now, at the age of thirty-four, his love is rooted in Dresden, where Voranger, meanwhile principal of Semperoper Ballet, lives with his wife, opera singer Antigone Papoulkas, and two sons. In early October we met there in a French bistro to talk about his career, his life and his vision of the art of ballet.

Voranger started to take ballet lessons around the age of six together with two of his his three sisters in his home village close to Aix-en-Provence in Southern France. He hadn’t attracted attention by his special fascination for dance; he liked to move in general, played football, bicycled and did athletics; dance was simply another outlet for his energy, another kind of sports. But for his mother it was easier to organize the children’s leisure time when all were at the same place. Moreover the lessons for Fabien were for free, maybe because he was the only boy in the school or because his talent already shone through. The village boys never teased him for dancing, because “I was the most pushy one, the leader of our little group of boys.”

When the family moved to a bigger city also close to Aix-en-Provence, his mother again enrolled the kids for ballet lessons at the local conservatory. Yet ten-year-old Fabien had changed his opinion; he had little enthusiasm: “The first time I was there I thought, my God, why do I have to do this? But it happened that I was a bit in love with one of the girls; and, needless to say, when she planned to do a summer course in Marseille, I wanted to go there as well. When we came to Marseille I met a boy of my age who trained at the École Nationale Supérieure de Danse de Marseille, the school Roland Petit had founded shortly before. He must have spurred on my ambition because we started to compete, who could jump higher and be quicker an so on, and I found I could do better than he.”

When the family moved to a bigger city also close to Aix-en-Provence, his mother again enrolled the kids for ballet lessons at the local conservatory. Yet ten-year-old Fabien had changed his opinion; he had little enthusiasm: “The first time I was there I thought, my God, why do I have to do this? But it happened that I was a bit in love with one of the girls; and, needless to say, when she planned to do a summer course in Marseille, I wanted to go there as well. When we came to Marseille I met a boy of my age who trained at the École Nationale Supérieure de Danse de Marseille, the school Roland Petit had founded shortly before. He must have spurred on my ambition because we started to compete, who could jump higher and be quicker an so on, and I found I could do better than he.”

The summer course was a decisive experience for young Voranger. Returning to his home conservatory Fabien informed his ballet teacher that he wanted to attend Petit’s ballet school in Marseille. She suggested he first try the audition for the Ballet School of the Paris Opera. “So I trained more intensely for a couple of months. The audition in Paris was in January, I got admitted and in February, aged twelve, I took up my training in Paris. That was one month after Rudolf Nureyev’s death in 1993. I always regretted not having met him; he was one of my role models.”

At that time Claude Bessy directed the Ballet School. She liked Voranger and fostered his talent. He was the first one to be allowed to skip a grade. Nevertheless he had a hard time at first. “In Southern France people are used to living outside, to go for a walk, to bicycle, meet friends and so on. In Paris, at the Ballet School, we never even left the building for a whole week. Maybe I didn’t really realize it back then because everything was new and I was excited. The first year went well but then I had a lot of discipline problems.”

At that time Claude Bessy directed the Ballet School. She liked Voranger and fostered his talent. He was the first one to be allowed to skip a grade. Nevertheless he had a hard time at first. “In Southern France people are used to living outside, to go for a walk, to bicycle, meet friends and so on. In Paris, at the Ballet School, we never even left the building for a whole week. Maybe I didn’t really realize it back then because everything was new and I was excited. The first year went well but then I had a lot of discipline problems.”

A quarrel with Bessy ended his time in Paris after two and a half years. Luckily he had always kept in touch with Colette Armand, director of the École Nationale Supérieure de Danse de Marseille. She also run a private ballet school, the Studio Ballet Colette Armand, where she took Voranger under her wings. “It was perfect. I knew Colette Armand from before, I lived in the house of one of her sisters, Pierrette Alleysson, so it felt as if being in a little family. Many ballet stars came round to teach at Armand’s school: Patrick Armand, Rudy Brians, Dominique Khalfouni, Jan Broeckx and others. I was the youngest, their baby; they fostered me.” Voranger needs the feeling of being protected, despite, as he later states, he is a strong-willed leader. “I’m sensitive towards emotional attention, I need to be loved.”

Prepared by Armand he won the “Prix Espoir” at the Prix de Lausanne in 1997 and was offered a scholarship. He could chose between returning to the Ballet School of the Paris Opera, going to Toronto and London. London wasn’t that far away so he decided on one year at the Royal Ballet School. Yet Voranger wasn’t happy with his success. “For several reasons it turned out a horrible experience. First I was in love with a ballerina in Wiesbaden so I used to fly to Frankfurt and from there go to Wiesbaden to see her. Second I had a Russian ballet master with whom I had a very hard time to understand his teaching method. And third London seemed smoggy and moldy; the ballet studios needed renovation and I though to myself: Where am I? After six months I got injured; my hamstring ripped and I left London ahead of time heading to Wiesbaden on crutches.” Again Colette Armand reached out to him. “She called me, telling me that

Prepared by Armand he won the “Prix Espoir” at the Prix de Lausanne in 1997 and was offered a scholarship. He could chose between returning to the Ballet School of the Paris Opera, going to Toronto and London. London wasn’t that far away so he decided on one year at the Royal Ballet School. Yet Voranger wasn’t happy with his success. “For several reasons it turned out a horrible experience. First I was in love with a ballerina in Wiesbaden so I used to fly to Frankfurt and from there go to Wiesbaden to see her. Second I had a Russian ballet master with whom I had a very hard time to understand his teaching method. And third London seemed smoggy and moldy; the ballet studios needed renovation and I though to myself: Where am I? After six months I got injured; my hamstring ripped and I left London ahead of time heading to Wiesbaden on crutches.” Again Colette Armand reached out to him. “She called me, telling me that  Roland Petit would want me to join his company.” Bypassing his graduation Voranger directly entered into Petit’s corps de ballet. “I was in Petit’s last creation, “Swan Lake” which is still in my head. One day I’ll ask to get a video of this “Swan Lake”. Perhaps I should bring it back on stage.”

Roland Petit would want me to join his company.” Bypassing his graduation Voranger directly entered into Petit’s corps de ballet. “I was in Petit’s last creation, “Swan Lake” which is still in my head. One day I’ll ask to get a video of this “Swan Lake”. Perhaps I should bring it back on stage.”

Voranger’s infallible gut instincts also guided the following steps in his career. In 1998, after Petit had quit, Marie-Claude Pietragalla became the company’s general director. “On one side that turned out to be very beneficial for me. I was sixteen or seventeen years old, still in the corps de ballet, but under Pietragalla corps members suddenly danced principal roles. She wanted to push the youngsters but on the other side the principal dancers were put on the back burner. Yet they were actually the stars and, in addition, they were my teachers who took care of me. So I was caught between two stools.” Pietragalla also picked certain dancers for small tours while the others had to stay at home in Marseille. Her strategy eventually undermined the company’s team spirit. Frustration spread. Finally Voranger decided to leave.

At that time Sylviane Bayard was at the head of the Deutsche Oper Berlin. Due to an injury of one of her dancers she offered Voranger a contract as a soloist. He accepted and, not even eighteen years old, moved to Berlin. “It was a fascinating time because of the diversity of dance being available. One could go to the Komische Oper and see something very modern; the State Opera danced more classical pieces, and we presented a style in between, a more neoclassical repertory. We danced, for example, Youri Vámos’s “Romeo and Juliet”

At that time Sylviane Bayard was at the head of the Deutsche Oper Berlin. Due to an injury of one of her dancers she offered Voranger a contract as a soloist. He accepted and, not even eighteen years old, moved to Berlin. “It was a fascinating time because of the diversity of dance being available. One could go to the Komische Oper and see something very modern; the State Opera danced more classical pieces, and we presented a style in between, a more neoclassical repertory. We danced, for example, Youri Vámos’s “Romeo and Juliet”  and his “Sleeping Beauty”, pieces by Ray Barra, Heinz Spoerli, Hans van Manen and Jiří Kylián. That was all new for me and pretty interesting. I remember my first role was in “Cinderella” by Valery Panov, actually an antiquated production but quite famous in the late 1970s. The only problems were politically bred. Funding was sparse and, for some inexplicable reason, there was no public. It might happen that shows in the huge Deutsche Oper were almost empty.”

and his “Sleeping Beauty”, pieces by Ray Barra, Heinz Spoerli, Hans van Manen and Jiří Kylián. That was all new for me and pretty interesting. I remember my first role was in “Cinderella” by Valery Panov, actually an antiquated production but quite famous in the late 1970s. The only problems were politically bred. Funding was sparse and, for some inexplicable reason, there was no public. It might happen that shows in the huge Deutsche Oper were almost empty.”

Later, in 2004, Berlin’s three ballet ensembles merged into the State Ballet Berlin. Yet back then the capital’s cultural policy was unstable; unfortunately it is still on a wavering course.

Voranger began to to look out for new options which turned up in the person of Heinz Spoerli. Spoerli, director of Zurich Ballet, offered him a contract. He already had assembled a list of roles which he proposed to Voranger during a business lunch. Tempting prospects, but when Voranger later tried to call him in Zurich, Spoerli was never available. Finally his secretary informed Voranger, that her boss had changed his mind. Today, convinced that Spoerli’s company wouldn’t have been the right place for him, he laughs about this strange incident.

His path to Dresden continued to be winding. Instead of going to Zurich Voranger joined the Vienna State Ballet in 2004, not knowing that Renato Zanella, the company’s director and chief choreographer, was about to leave. Zanella was succeeded by Gyula Harangozó in 2005. Voranger quickly found out that the chemistry between him and Harangozó wouldn’t be right. He already thought of quitting ballet all together at the end of one year and following his girlfriend, an Australian ballerina, to her home country. Fortunately he had met Aaron S. Watkin and Laura Graham in the meantime. Both had been involved in a production on Mozart’s Requiem in Bolzano where Voranger again jumped in for an injured dancer.

His path to Dresden continued to be winding. Instead of going to Zurich Voranger joined the Vienna State Ballet in 2004, not knowing that Renato Zanella, the company’s director and chief choreographer, was about to leave. Zanella was succeeded by Gyula Harangozó in 2005. Voranger quickly found out that the chemistry between him and Harangozó wouldn’t be right. He already thought of quitting ballet all together at the end of one year and following his girlfriend, an Australian ballerina, to her home country. Fortunately he had met Aaron S. Watkin and Laura Graham in the meantime. Both had been involved in a production on Mozart’s Requiem in Bolzano where Voranger again jumped in for an injured dancer.

Two years later, in 2006, Voranger found a message on his answer phone which he had forgotten to listen to for some time. The message was from Watkin, who was about to become artistic director of the Semperoper Ballet in Dresden. He invited Voranger to join the newly assembled company.

“Back in Marseille, one of my teachers, a very famous dancer of Roland Petit, Rudy Brians, once had said to me: There will be always someone who can do more pirouettes than you, who is technically superior. So the most important thing in a career is to find someone who makes something of you. Looking back this was my guideline, this was the reason why I had entered several companies. In this respect going to Dresden in 2006 was the best thing that could happen to me. I’ve a very good relationship with Aaron, we respect each other and I feel understood by him.”

“Back in Marseille, one of my teachers, a very famous dancer of Roland Petit, Rudy Brians, once had said to me: There will be always someone who can do more pirouettes than you, who is technically superior. So the most important thing in a career is to find someone who makes something of you. Looking back this was my guideline, this was the reason why I had entered several companies. In this respect going to Dresden in 2006 was the best thing that could happen to me. I’ve a very good relationship with Aaron, we respect each other and I feel understood by him.”

Yet there had been a low. Not because of any dissonance within the company but caused by a characteristic of the art of ballet itself. Voranger wants to create, to express himself as an artist. Mainly recreating already existing roles doesn’t fulfill him. Hence, three years ago, when his second son was born, he was again ready to give up dancing. But at that time Stijn Celis planned his new “Romeo and Juliet” for the Semperoper company and insisted on Voranger being his Romeo. Voranger agreed and instead of definitely leaving decided to take six months of parental leave. When coming back and looking at the cast list for “Romeo and Juliet” he learned that he was only in the second cast for Tybalt. That was quite a shock! After some major cast changes he indeed danced Tybalt, and, as he puts it, had the right attitude for depicting the bad, aggressive guy. The role came out perfectly and at the end Voranger enjoyed dancing it.

The spectrum of his roles is varied. Other rather dark figures in his repertory are Tybalt or Rothbart, but he was also Romeo, Petruchio in John Cranko’s “Shrew”, Potiphar in “The Legend of Joseph” by Celis, and Albrecht in David Dawson’s “Giselle”. “Basically there is no big difference between being the bad guy or the good one. Once you honestly plumb yourself you only need the right direction, you need to pick up the right element inside. For being the good guy you have to go to exactly the same place, but pick up what is right for being a positive personality. The process it the same. You have to represent the honesty of the character which you are about to depict. You should be occupied by another energy. If one’s own personality covers the authenticity of the role it wouldn’t feel right for me.”

The spectrum of his roles is varied. Other rather dark figures in his repertory are Tybalt or Rothbart, but he was also Romeo, Petruchio in John Cranko’s “Shrew”, Potiphar in “The Legend of Joseph” by Celis, and Albrecht in David Dawson’s “Giselle”. “Basically there is no big difference between being the bad guy or the good one. Once you honestly plumb yourself you only need the right direction, you need to pick up the right element inside. For being the good guy you have to go to exactly the same place, but pick up what is right for being a positive personality. The process it the same. You have to represent the honesty of the character which you are about to depict. You should be occupied by another energy. If one’s own personality covers the authenticity of the role it wouldn’t feel right for me.”

This season Voranger was promoted to principal which he takes as an appreciation of what he is, what he is good at, not what he could be. “I’m unable to fake a role; if I cannot be real, if I cannot be true, I can’t do anything.” Prince Désiré in “The Sleeping Beauty” wouldn’t be his metier and Watkin knows that. “It is crucial to be respected as an artist, to have the opportunity to develop your abilities, to express what is inside you. Matching your performance to the video recordings of how previous dancers interpreted a role isn’t the actual sense of what is called an artist. Sadly, there are not many opportunities to really contribute one’s creative talent.”

One important exception was David Dawson’s “Tristan + Isolde” which premiered last season. Tristan was created on Voranger. “There was no reference piece in ballet, we had to find steps, characteristic movement languages for each figure, we had to give birth to roles which for the ballet world didn’t exist.” Ten weeks of intense work in the studio brought out an extraordinary piece, emotionally intense, highly touching, brimming with expressive dance. “This ballet is the most challenging for me, physically, technically and emotionally. It is a killer, but that is part of the purpose. I always draw references to “Manon”. In “Manon” the main characters’ final pas de deux lasts four or five minutes and quite some time they lie on the floor. Ours lasts seven and a half minutes and I’m running all the time.” Voranger laughs heartily.

One important exception was David Dawson’s “Tristan + Isolde” which premiered last season. Tristan was created on Voranger. “There was no reference piece in ballet, we had to find steps, characteristic movement languages for each figure, we had to give birth to roles which for the ballet world didn’t exist.” Ten weeks of intense work in the studio brought out an extraordinary piece, emotionally intense, highly touching, brimming with expressive dance. “This ballet is the most challenging for me, physically, technically and emotionally. It is a killer, but that is part of the purpose. I always draw references to “Manon”. In “Manon” the main characters’ final pas de deux lasts four or five minutes and quite some time they lie on the floor. Ours lasts seven and a half minutes and I’m running all the time.” Voranger laughs heartily.

Having the opportunity to work with David Dawson is important for Voranger. “For me, David furthers the art form because he creates a new language in dance. And isn’t that the main purpose of choreography?” Dawson and Voranger share a similar idea of what the art of ballet can and should be. “We both rather want to be dominant when working, we are similar sensitive, we project similar emotions and we have the same insecurities. That sometimes causes clashes. Yet our work is based on mutual trust. David’s dance style, his language, is the most familiar to me. He makes me feel free and really comfortable to give myself into the work.” And the gods seemed to smile upon their collaboration. When Dawson asked Voranger to partner Jurgita Dronina in “A Sweet Spell of Oblivion” at the Dance Open Gala in St. Petersburg in 2013, both were awarded for the best duet. “I couldn’t believe it! Six months earlier I had wanted to stop dancing. And then this huge stage in St. Petersburg which actually had made my heart sink!” Also the story of Tristan began at this gala weekend. Shortly before the show Dawson had told Voranger, that he wanted to create Tristan on him. “For me the piece premiered on this evening in that moment.”

“Tristan + Isolde” was also in another respect meaningful. “I always feel very sad about ballet being an ephemeral art. Whatever I do, once it is done it is gone. Yet being Tristan was an achievement for me. I feel as if leaving a little stone behind. Otherwise I might have left nothing.”

“Tristan + Isolde” was also in another respect meaningful. “I always feel very sad about ballet being an ephemeral art. Whatever I do, once it is done it is gone. Yet being Tristan was an achievement for me. I feel as if leaving a little stone behind. Otherwise I might have left nothing.”

Next to the all-too-fleeting art of dance Voranger loves architecture. Once a book about Dresden’s opera, its theaters and ballrooms before the bombing motivated him to search the city for traces of old ballrooms. “It is incredible how many existed! But many of the ones which weren’t destroyed became warehouses or storage places. You would cry when seeing what was made out their beautiful art nouveau!”

Some years ago he bought one of those ballroom buildings in a small village near Dresden. Together with his father, with whom he had already built and renovated a few apartments in Vienna, he began with sealing the roof. At the moment the building is empty but perhaps, one day, Voranger might convert it into an open studio. “I am always busy in my mind and maybe the ballet summer course I initiated in Berlin can take place in my ballroom some day.” Behind the summer courses is “ART of” – INNOVATIVE Ballet Master Class, a project Voranger founded with Oleg Klymyuk, a former dancer of Semperoper Ballet, in 2012. The program includes workshops and ballet classes in Berlin and Mainz taught by a remarkable variety of professionals in the field.

Bringing together different people, establishing new contacts, realizing unusual ideas are Voranger’s strengths. He has a strong mind, he certainly has no tunnel vision on ballet, instead he is an open-minded thinker. Not for nothing does he speak highly about Sergei Diaghilev.

Well, isn’t a second Diaghilev always needed?

(The interview has been edited for clarity.)

| Links: | Homepage of Semperoper Ballet | |

| Ian Whalen’s Homepage | ||

| Photos: | 1. | Fabien Voranger |

| 2. | Courtney Richardson and Fabien Voranger, rehearsal of “Giselle” by David Dawson, Semperoper Ballet Dresden | |

| 3. | Courtney Richardson and Fabien Voranger, rehearsal of “Giselle” by David Dawson, Semperoper Ballet Dresden | |

| 4. | Fabien Voranger, rehearsal of “Giselle” by David Dawson, Semperoper Ballet Dresden | |

| 5. | Fabien Voranger, rehearsal of “Giselle” by David Dawson, Semperoper Ballet Dresden | |

| 6. | Fabien Voranger (Rothbart) and Svetlana Gileva (Odile), “Swan Lake” by Aaron S.Watkin, Semperoper Ballet Dresden | |

| 7. | Fabien Voranger (Rothbart) and ensemble, “Swan Lake” by Aaron S.Watkin, Semperoper Ballet Dresden | |

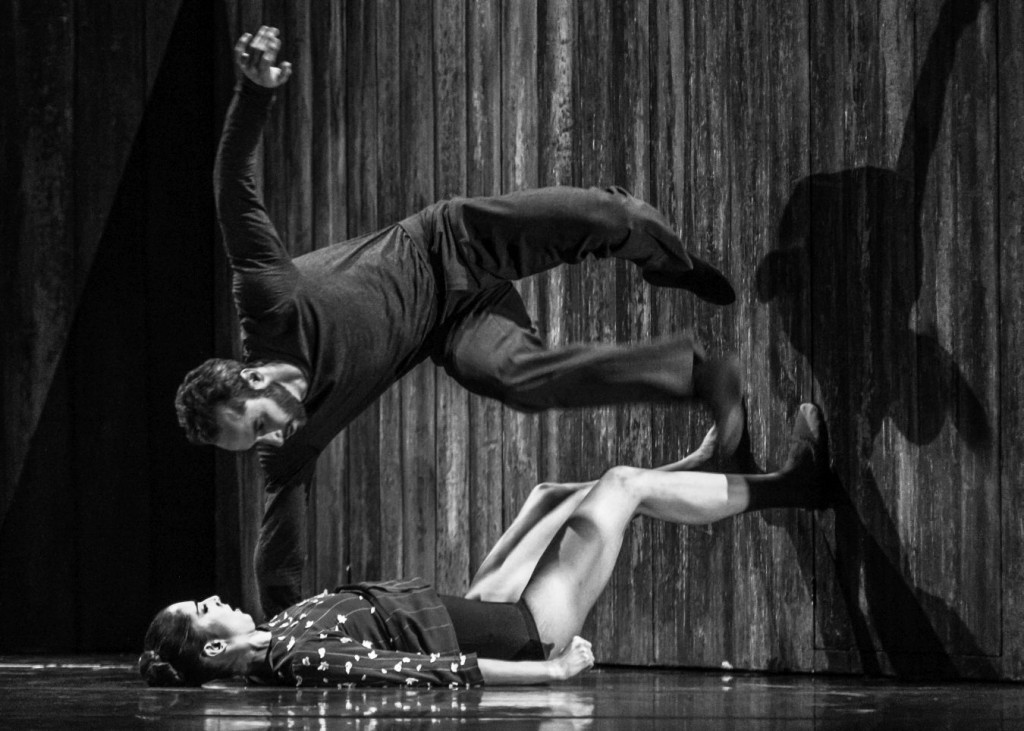

| 8. | Julia Weiss and Fabien Voranger, “Walking Mad” by Johan Inger, Semperoper Ballet Dresden | |

| 9. | Fabien Voranger, “Im anderen Raum” (“In another sort of room”) by Pontus Lidberg, Semperoper Ballet Dresden | |

| 10. | Fabien Voranger, rehearsal of “Giselle” by David Dawson, Semperoper Ballet Dresden | |

| 11 | Fabien Voranger, rehearsal of “Giselle” by David Dawson, Semperoper Ballet Dresden | |

| 12. | Fabien Voranger and Courtney Richardson, rehearsal of “Giselle” by David Dawson, Semperoper Ballet Dresden | |

| 13. | Courtney Richardson and Fabien Voranger, rehearsal of “Giselle” by David Dawson, Semperoper Ballet Dresden | |

| all photos © Ian Whalen 2015 | ||

| Editing: | Agnes Farkas |